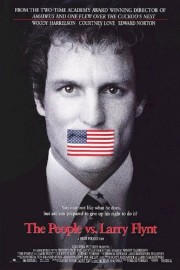

The People vs. Larry Flynt

It’s been 20 years since I first saw “The People vs. Larry Flynt” when it went into wide release in early 1997, and it remains a fascinating biopic. That should not be a surprise, because the film’s director, Milos Forman, is a master of the biopic form. His first Oscar was for “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest,” but his most memorable films after that were all about eccentric and compelling real-life characters- “Amadeus,” about Mozart, “Man on the Moon,” about Andy Kaufman, and “Larry Flynt,” about the publisher of Hustler magazine. None of these people have anything in common but one thing- they revolutionized their fields. I’m not saying Larry Flynt is gifted in the same way of Mozart or Kaufman, but he changed the game in pornography, and more important, how it is viewed in terms of free speech in America. That is a milestone similar to anything those two accomplished, regardless of how you feel about what he does.

One thing that struck me in watching the film again was in how one moment still rings true. It comes after Larry Flynt has gotten out of jail for the first time, and he is speaking to supporters. He is Patton-like in front of screen as images of nudity and sex are followed by images of war and violence. He is making a point of our hypocrisy about how we treat the very natural naked body, and act of love, as sinful and not to be discussed compared to the amorality of violence against our fellow man. It was a point that was painfully obvious at the time the movie is set, at the time the movie was released, and is still relevant now. It is one thing to want our children to be exposed to sex and lovemaking when their emotionally ready to be, but our lack of care, as a society, about violence, and treating that as a natural human act, is more disruptive, and more harmful. I was reminded of Kirby Dick’s “This Film is Not Yet Rated,” about the movie ratings system, during that moment, and the two films would make a great, important double feature on censorship, and how America champions free speech but also suppresses it in ways that aren’t illegal, but are damaging to us as a society.

This film was written by Scott Alexander and Larry Karaszewski, who would go on to write “Man on the Moon” for Forman, and who were coming off another great, quirky biopic, “Ed Wood,” when this film came out. We start in 1952, with Larry and his brother, Jimmy, selling moonshine in Kentucky as kids. From there, 20 years later, they would graduate to selling sex, first at strip clubs in Cincinnati, later moving into publishing nude pictures. Their first attempt is as a pamphlet to try and drum up business for their club, then later finding a niche for low-level sleaze that Playboy and Penthouse just wasn’t offering. It’s slow moving for them at first, but when he publishes nude photos of former first lady Jackie Kennedy, suddenly he is king of the heap. With the fame, however, comes a big ‘ol target on his chest, with many of the arrows coming from the religious right, which was just coming in to its own as a political force in the ’70s. His most formidable opponent would become Jerry Falwell, who he goats into a legal battle with a salacious piece of parody that becomes the center of a landmark case in front of the Supreme Court he and his lawyer, Alan Isaacman, find themselves arguing. Is what Larry Flynt publishes protected speech, or do certain things fall outside of the protections of the First Amendment?

Of the three Forman films I mentioned above, it seems to me the one most akin to “The People vs. Larry Flynt” is “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.” There’s much in common with Woody Harrelson’s rambunctious Larry Flynt, a role for which he earned a well-deserved Oscar nod, and Jack Nicholson’s R.P. McMurphy. Time and time again, they get pleasure out of poking the bear of the establishment, but while the establishment reins in McMurphy before the rebellion of the Chief and his escape, Flynt wins in the end in almost every single way, although he would lose his wife, Althea (Courtney Love) to AIDS, and the use of his legs to a sniper’s bullets after a court hearing in Georgia. Much was made of Love’s performance as the former stripper when it came out, and while she still does terrific work, it feels like the initial rapture over her performance was overdone. Many critics cried foul when she didn’t get an Oscar nomination like Harrelson did, but thinking about her at the time compared to her role, it feels like Forman (who would later cast her in “Man on the Moon”) cast her to type, and got what he wanted out of her. Harrelson is the real revelation here, putting aside the awe shucks “Cheers” persona he had cultivated and turning in a performance that was nothing short of an opening salvo of things to come in later films. This was a fireball of a performance, with Love, Edward Norton (as the long-suffering Isaacman) and others along for the ride. You can’t help but take your eyes off him, and find his Larry Flynt as obscene, absurd and vital to the past 45 years of American history as he finds himself. His story is one all who support the First Amendment need to take seriously, whether you like what he does with it or not.