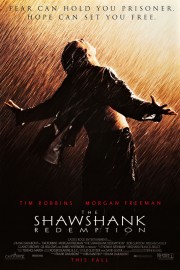

The Shawshank Redemption

I remember the skepticism about “The Shawshank Redemption” when it was released. I remember its initial failure, and also, how Warner Bros. brought it back multiple times in theatres, including one to try and take advantage of the Oscar nominations it received. I also remember not seeing it until home video because…I wasn’t interested. I would have made a point of seeing it in theatres a decade later; but I’m one of the many it just didn’t seem interesting for.

This is only the second time I’ve seen Frank Darabont’s beloved prison drama since 1994, and it feels like a film I should adore. In the past decade I’ve really taken to films about spiritual journeys and hope in the face of darkness, but I haven’t felt that urge to revisit “Shawshank” until now. In revisiting it, I absolutely get the love for it- when it is within the walls of Shawshank prison, it is captivating- but I also feel like it hits its buttons in an overtly sentimental fashion that doesn’t land the way Darabont wants it to, especially given the ending. If you’ll hold your vegetables to be thrown until the end, please.

It’s a damn tragedy that, after “The Mist,” and after the fiasco of his exit from “The Walking Dead,” Darabont has not made another film since. Apart from being one of the best adapters of Stephen King for the big screen, he has a gift for character, directing actors, and putting us in a time and place that is engrossing. Even though the appearances of Andy Dufresne (Tim Robbins) and Red (Morgan Freeman) don’t really change over the course of the two decades they occupy Shawshank together but for subtle ways, we get the perception through the performances that these characters have lived, and become friends, for decades, and that’s not just because Robbins and Freeman are two of our great actors; Darabont has written the characters in a way that we see shifts in their views on life, and directed them in a way that gives us physical performances that help reveal what these characters are thinking, and how they are feeling. The same can be said for characters and actors along the edges of Andy’s and Red’s stories, like Bob Gunton’s Warden Norton, William Sadler’s Heywood, and James Whitmore’s Brooks, although there’s a more distinct change in those characters’s appearance than the ones we see in Andy and Red, but that only enforces how impressive it is on Darabont’s part that we still sense the passage of time in this film.

The storytelling at work in Darabont’s film is enough to merit the Oscar love, and the love audiences have shown it as they’ve discovered it since. The way he sets up Andy, and the crime he allegedly did, in the beginning before changing perspectives to Red, whose words and point-of-view we will see the rest of the film through. The way we always are left wondering about the truth of whether Andy did or did not kill his wife and her lover, and whether that even matters to how we feel about him. The way Andy conducts himself while in prison, which is sometimes a mystery until it isn’t necessary to keep the secret any more. The way we see characters behave out of their own self-interest because Andy can do something for them, and the way Andy turns the tables on that when it suits them. We see a moment of potential violence between two characters in prison, and the reason for it is complicated and given shade to the one threatening violence. We see how moments of seeming triumph give way to tragedy because life just isn’t fair, some times, and humans can be cruel if their self-interests are threatened.

This is wonderful film craft on the part of Darabont and his collaborators, especially cinematographer Roger Deakins (who knows just how to bring emotion to images through lighting and shot composition) and composer Thomas Newman (whose familiar instrumentations and motifs are just right for the story being told), and yet, I feel like something goes fundamentally wrong with the ending, which feels like a very obvious Hollywood ending as opposed to an honest ending for this story. Granted, it’s lovely symmetry to have Andy and Red essentially change positions in their friendship, and I don’t have a problem with the idea that the both get out of Shawshank, or with how they do so. (Hell, watching the last of Red’s three parole hearings, and the way he “convinces” them, I imagine them thinking his “Hell with it” attitude is what proves he’s ready to be back in society rather than any real reform.) The last image of the film should be implied, however, not something that we actually see. And I actually like the idea of the last thing we see being Red up against that wall, reading Andy’s words to him, and fade to black. Everything after that just doesn’t work for me when everything that came before it did because it didn’t follow Hollywood conventions.

You may now throw your vegetables at me…