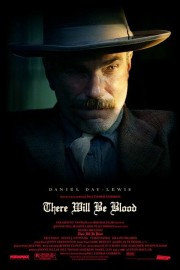

There Will Be Blood

In his fifth, and boldest, film to date, writer-director Paul Thomas Anderson has taken the two most controversial constituencies of contemporary American politics- Big Oil and Big God- and set them on a spiritual and financial collision course which leaves both bruised and bloody. It’s not fun to watch, but damned if it’s not compelling. As someone who found Anderson’s more intimate offerings (“Hard Eight” and “Punch-Drunk Love”) more altogether fascinating than his more jumbled, epic offerings (“Boogie Nights,” “Magnolia”), it’s almost exhilarating to see him tell a riveting, character driven story within a grand scope of not only three decades but about 2 1/2 hours that doesn’t fall under the weight of its’ own pretensions. I say “almost exhilarating,” however, because it does begin to sag about midway through the movie- not because the story fails to interest, but because it begins to slow its’ momentum.

I’ve never read Upton Sinclair’s 1927 novel “Oil!,” which Anderson has adapted into “There Will Be Blood.” And from everything I’ve read of the movie, I’m not missing out- Anderson has chosen it for his subject and structure, not necessarily its’ story. (It’s almost enough to make me want to rewatch “Boogie Nights,” which I’ve long held as an L.A. porn industry version of “GoodFellas”- which followed the same structure- except that Anderson doesn’t make any significant points in that overpraised epic that Scorsese hadn’t made already.) He’s also chosen it, no doubt, for its’ timely relevance as a way of digging deep into the one thing that corrupts both industries at work in the story (oil drilling and evangelical religion)- greed. If nothing else, his film nails both targets with razor-sharp precision.

At the center of “There Will Be Blood” is Daniel Plainview (Daniel Day-Lewis), a miner who switches his vice from prospecting gold to uncovering oil very early on in the film. One mining accident leaves him with a limp he’ll carry the rest of his days; another one will leave a young baby orphaned for him to raise as his own. Years after both, Plainview is a successful and charismatic “oil man” who, with his ward H.W. (Dillon Freasier), is very good as coming off as a family man when a potential deal requires it. A juicy one comes walking into his office in the person of Paul Sunday (Paul Dano), who points him towards his family’s ranch in Little Boston as a potential coup for Plainview and his drillers- Standard Oil is already scoping out the land themselves.

Plainview agrees, and sets up shop by leasing much of the town’s land for his drilling. Trying to keep him on a short leash is Eli Sunday (also Dano), Paul’s twin brother and a preacher in town (could his name be short for Elijah?) who only agrees to Plainview’s demands after securing some money for himself to build his church, named the Church of the Third Revelation (curious by the choice, I opened my mother’s Bible and turned to Revelations Chapter Three, whose Third verse states, “Remember then what you received and heard; keep that, and repent. If you will not awake, I will come like a thief, and you will not know at what hour I will come upon you.” Consider this when contemplating the film.). But Plainview reneges on the deal (and a later one where he was to let Eli bless an oil derrick), beginning a feud that would consume both men for years.

Like Charles Foster Kane in “Citizen Kane,” Plainview is a man blinded by insatiable greed, with no relationships built for anything more than gain- when H.W. is deafened in an accident which sets an oil derrick ablaze (a remarkable sight captured with burning intensity by cinematographer Robert Elswit that serves as a symbolic image illuminating the film’s themes), Daniel sends him off to a school far away, as he’s no good to Daniel until he finds another way to exploit him (Freasier is a find, capable of both the love and disdain a young man can feel towards his father, even when he displays both qualities without words). The possibility of a half-brother named Henry (the excellent Kevin J. O’Connor, barely recognizable) begins to chip away at Daniel’s hardened core a little bit more until he feels like he’s caught Henry in a lie- discovering the truth not long after the falling out forces tears from his eyes more than even H.W.’s deafness, which coincided with his realization of just how much oil he could pump out of Little Boston. To say that Plainview isn’t a people person is to put it lightly- he puts it best when he says, “I look at people and I see nothing worth liking.”

Spoken like a true sociopath; greed and pride are Plainview’s twin sins for which he will never repent, even when he’s forced by Eli to stand up in front of a congregation and say that he is a sinner during a baptism- for Daniel, it’s a means to an end, which will mean more land for him, more oil for him, the chance to create a pipeline to the ocean, and success he can throw in the face of competitors who thought he’d fall on his face without. Like Kane, there’s no change evident in Plainview from first frame to last. Unlike Kane, however, there’s no “Rosebud” to renew his humanity, either; any hope that H.W. might allow is shattered in their final, painful scene together, with the now-older son cutting ties with the emotionally-destructive dad in a way that liberates him, and even gives him hope despite leaving him without a parent of his own.

The destructive forces of family and sin are common themes in Anderson’s films, from the father figure atoning for his sins with guidance and world-worn wisdom in the underrated “Hard Eight,” the family of pornographers torn asunder by greed and rocked by moral questions in “Boogie Nights,” the emotional scarrings that define families and destinies in “Magnolia,” and the psychological toll of emotional abuse at the hands of overbearing siblings in “Punch-Drunk Love.” But for the first time in his work, Anderson’s explorations of these themes seem to come from somewhere deep within the characters, not from the ideas of a screenwriter, and not only from the central relationship between Daniel and H.W.- we see in the Sunday’s how loyalties are divided by greed. Paul has tipped off Plainview of his family’s land, one suspects for his family’s gain. However, after his father is swindled on the deal from Plainview, Eli admonishes his family for their stupidity; of course, Eli’s more concerned, it seems, with gaining further funding for his church than his family’s well-being. It’s curious how Paul is never seen again after his meeting with Plainview; are he and Eli really supposed to be twins (as I’ve read), or is Eli scripting his own parable with which he can teach from? A tantalizing question that the film never answers, even with the finale in which Daniel and Eli- both true iconoclasts- mentally and physically duke it out, not really leaving anything decided, although allowing for an ending the film- and the characters- rightfully deserve.

Of course, such an ending would be impossible to really buy into without great actors in the roles, and Anderson has landed tremendous work from both Day-Lewis (besting his role as “Bill the Butcher” in Martin Scorsese’s “Gangs of New York” in calculating wickedness) and Dano (a revelation after his tragic role in the comic “Little Miss Sunshine”). Daniel Day-Lewis has gotten all the press, and rightfully so, staying true to the character’s motivations and mad glint of greed even as he shows hints of the self-loathing man beneath; if I had one problem with the performance, however, I would say that its’ one-note is hard to sustain compellingly in a film with so few compellingly-drawn supporting characters. Damned if Day-Lewis doesn’t sustain it, but I think the fever pitch of it has caused some overpraising by critics. Dano’s the one that’s probably gonna stick out in my memory, anyway- how he failed to miss Oscar’s final five is a crime. He captures the transparent devilry at work in people who preach by the cloth but act for their check book- fundamentalist talking heads of all religions take note; we have your number. Making it all the more effective is Dano’s baby-faced features- it’s always the ones you least suspect you have to be the most careful with.

As Day-Lewis and Dano’s characters collide onscreen, Anderson’s directorial energy fully blossoms before our eyes; the first fifteen minutes of wordless storytelling (in which we see the development of Plainview into the character we’ll follow throughout the rest of the film) is some of the most astonishing he’s ever done. Aided, in large part, by a score by Radiohead rocker Johnny Greenwood that’s makes experimental music appear downright commercial, Anderson fashions a film epic in ideas, themes, and story, if not in budget and pyrotechnics. Doesn’t matter- I’ll take a film whose definition of “epic” falls more into the first three categories anyway; it’s more likely to find itself watched more as the years go by.