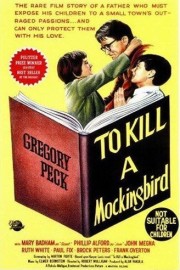

To Kill a Mockingbird

The only time I had watched “To Kill a Mockingbird” was in high school, in English class, after reading Harper Lee’s beloved novel. I didn’t remember a lot about it except that I watched it, so I knew, in order to formulate a proper opinion of the classic film, of course a new watching would be necessary. After Harper Lee passed away last week, and seeing it was available on Netflix Streaming, the stars seemed to align for me doing so. Looking at Roger Ebert’s 2 1/2 star review of the film from 2001, however, I wondered, “Is it really that great a film, or is it just widely accepted as one, an ‘established classic,’ as it were?”

To say that Hollywood has had a sketchy relationship with the issue of racism in movies is an understatement, given that the first landmark of American cinema was D.W. Griffith’s “Birth of a Nation,” which is a stunning work of technical filmmaking that is marred by abhorrent racism during the second half of the film, and the highest-grossing film of all-time (when adjusted for inflation) is “Gone With the Wind,” which is not much better on race issues. Still, in the century since, some films have come through that look at the harsh realities of America’s racist past and present with more honesty and passion, like “Malcolm X,” “Do the Right Thing,” “Amistad,” “12 Years a Slave,” “Dope” (which I just watched yesterday, and was immediately taken by) and “Straight Outta Compton.” To put “To Kill a Mockingbird” in the company of some of these films seems wrong, but the truth is, while Robert Mulligan’s film looks at the topic, as it’s namesake novel does, through the eyes of a white child in the Deep South, there are some painful realities and harsh truths that still stick with us today, leading to an overwhelming emotional impact that only helps those stick more acutely. That I watched this 54-year-old film, and found parallels with events happening today when it comes to miscarriages of justice towards African Americans in this country, only helped the film land it’s emotional punches with more force than it probably should have.

The film starts with narration by Kim Stanley as the grown-up Scout, the tomboy daughter of Atticus Finch (Gregory Peck). Atticus is a lawyer and single father in the fictitious town of Maycomb, Alabama in the 1930s. It is a small town, where the roads aren’t paved and everyone walks everywhere. We see Scout (Mary Badham) and her brother, Jem (Phillip Alford) playing in the summertime, and Walter Cunningham Sr. come to drop off nuts to Atticus as payment for some legal assistance he gave the man. Walter is shy about his poverty, and is paying the only way he can, and Atticus is grateful. One day, a local judge comes by and tells Atticus he has been appointed as defense counsel for Tom Robinson (Brock Peters), a black man in town who has been accused of raping and beating a white woman, Mayella Ewell (Collin Wilcox Paxton). Her father, Bob Ewell (James Anderson), cannot believe Atticus, who believes everyone is to be treated fairly, is defending this “nigger,” and is appalled at the notion that he believes Tom’s story over his. When this happens, Scout and Jem, who have been shielded by such things by their father, grow up quickly when they’re exposed to the realities of what their town is like.

The scenes that everyone remembers are the courtroom scenes, wherein Atticus punches holes in the case the Ewells and the prosecution presents against Tom Robinson, but they are ultimately less powerful than other scenes in the movie. Yes, it packs an emotional charge to watch Peck, as Atticus, passionately defend Tom, but it’s outside the courtroom where the film, and it’s story (adapted from Lee’s book by Horton Foote, who won an Oscar for his script), gain it’s weight. Probably the most riveting scenes are where Ewell comes to see Atticus at the Robinson’s house, once before the trail and once after, and taunts not only Atticus as a “nigger lover,” but also frightens Jem, who is in the car, and a scene right before the trial, where a lynch mob comes to the courthouse jail, and Atticus is there, standing watch. Scout, Jem and another friend are watching Atticus from afar, and make their way through the crowd, and insist on staying with Atticus, and standing with him in opposition to the mob. Scout recognized Walter Cunningham Sr., and treats him with the same friendly demeanor we witnessed earlier in the film, and the guilt that inspires in the man causes him to lead the crowd in dispersing. Afterwards, the kids leave, and Atticus stays watching over his client. The work of an optimistic fiction writer? Perhaps, as we know from historical records that real lynch mobs were not so easily sated, but it’s still a bold stroke in a movie that brims over with hopefulness. This may be a film that irons out the wrinkles and complexities of racism more than it presents them in their wickedness, but it still means something to watch a film look at the topic, and not shy away from all of the evil it engenders.

Of course, there’s one part of the story I have not covered above, and that is the character of Boo Radley. Through much of “To Kill a Mockingbird,” Boo Radley exists only in rumors and the unknown. Is he locked up by his old father? Is he crazy? What would happen if the children saw him? The Radley house is that house we all had near us growing up, which felt like an forbidden place to go, as we didn’t know what we might find there. At the end, we finally see him, after Scout and Jem have been attacked on the way home from a Halloween party. Boo Radley is played by Robert Duvall, in his film debut, and watching the film again, I couldn’t help but feel a bit let down by the payoff. He’s an interesting character, and he provides closure to the story, but when I think of the title, To Kill a Mockingbird, and it’s symbolic meaning in the context of the story (to kill a mockingbird is a sin, as would Atticus bringing the private Boo into the open for his heroism), I feel it is misplaced. The sin in this story is the death of the innocence of childhood for Scout and Jem. They start out the story as kids, but are exposed to grown-up troubles and complex social issues in a way they are not prepared for. They will never be the same after this experience, and will be unable to just enjoy life as a child would without thinking of what lies ahead as an adult. Atticus is unable to protect them from this life anymore. Now, they must start to do that for themselves. That first taste of what pain life has can be difficult for a child to process, but Scout and Jem have a good father who will help them along the way.