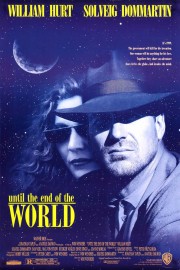

Until the End of the World

Sometimes, if you come to a movie through an alternate version- namely, a Director’s Cut- for the first time, you’ll want to go back and watch any earlier versions that may have existed to see any differences. I never want to go and watch the 2 1/2 hour version of Wim Wenders’s “Until the End of the World” that American audiences got in 1991. I cannot imagine how it could have possibly have worked as any other than a nearly 5-hour “ultimate road movie” about two people, and others they meet along the way, as they go to what feels like the end of the world, at a moment where that feels like a distinct possibility. This is a masterwork of epic storytelling; the emotional aspect of it, however, is not as strong throughout. That will not matter- Wenders has a singular experience in store.

No discussion of “Until the End of the World” would be complete without taking a deep dive into its soundtrack album. I’m honestly surprised that I’ve relented for so long in getting this one, because not only does it have one of my favorite U2 songs from this era (“Until the End of the World,” from their album, “Achtung Baby”), but the score was composed by Graeme Revell. If that name is familiar to you from this site, it’s because he composed by favorite score of all-time, “The Crow.” Like that film, “Until the End of the World” is a seamless and brilliant melding of songs and score to the point where they compliment one another, and one almost bleeds into the other. That’s one of the things I have long appreciated about Revell’s score for “The Crow”- he doesn’t traffic in traditional orchestral scores; he brings a pop/rock sensibility to them that also allows haunting musical themes to emminate from it- other than “The Crow,” this might be his best score.

When it came to compiling the soundtrack for this film, Wenders called in personal favors from some of his favorite artists, with one caveat- try to imagine what music you’ll be making at the end of the decade, as the film takes place in 1999. This results in song by Lou Reed, Talking Heads, Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds, and T-Bone Burnett that are evocative, unusual, and captivating to listen to. The tracks by Julee Cruise and Jane Siberry have a familiar sound to them if you’ve heard songs they’ve contributed to “Twin Peaks” and “The Crow” before. Meanwhile, the two biggest names on the soundtrack- U2 and R.E.M. (not to discount the popularity of Elvis Costello or any of the above artists)- arguably didn’t go far enough; sure, both “Until the End of the World” and “Fretless” are very much representative of their aesthetic that decade, but anyone familiar with their work closer to the millennium knows they undersold what their music would sound like later in the decade. They’re both brilliant songs, though, and Wenders deploys them fantastically throughout the film.

So, about that film. I fully believe that it took Wenders six hours to pitch the story of “Until the End of the World,” conceived with his lead actress- Solveig Dommartin- to Australian author Peter Carey, with whom he wrote the screenplay for this epic film. (The idea that a 20-hour version of this film existed at one point both boggles my mind, and doesn’t surprise me in the least.) The film has romance, science-fiction, elements of film noir and detective stories, and an apocalyptic cloud hanging over it that influences every frame of this story. There’s also a novelistic approach to the story as one being told to us. The one doing the telling is Eugene Fitzpatrick (Sam Neill), who is also a key character in the story, and whom is the husband of Claire Tourneur, the character played by Dommartin. Is the surname Tourneur a reference to Jacques Tourneur, the director of “Cat People” and “Out of the Past?” It would not surprise me. Nothing should really surprise you about “Until the End of the World” except how damn engaging it is at almost five hours long, because really, there’s not enough story in it to feel like every moment is important. And yet, I wouldn’t cut a moment from this film in its 287-minute form. Even shots where the narrative seems to pause, and it’s just landscapes, are indispensable to the experience of this film, and the cinematography by Robbie Muller is astonishingly beautiful. This is a visionary experience alongside “2001: A Space Odyssey,” “Apocalypse Now” and “Andrei Rublev,” where conventional narrative gives way to unorthodox cinematic tone poem, and then flips its way back to the narrative as the film suits itself.

That narrative starts with Claire caught in a traffic jam, caused by people fleeing potential impact sites of an Indian nuclear satellite which has gone out of control, and re-entered the atmosphere. She escapes the highway, only to get in a car crash with two bank robbers, who give her the money to take to Paris. While returning to Paris, she meets a man named Trevor McPhee (William Hurt), and offers him a ride to Paris with her. He is on the run from a mysterious man, who works for someone Trevor has stolen from. As they depart, he takes some of the money from her. She then goes to Berlin, hires a private detective (Phillip Winter, played by Rüdiger Vogler) to track him down. When they do, he gets away. They then track him down to Moscow, where Eugene meets them with more money. Then, Claire follows him on the Trans-Siberian Railway, through China, and eventually to Japan. At this point, we know Trevor’s name is really Sam, and he has been stricken blind. At this point, there is a profound connection between them, and they then go to San Francisco, and finally, make their way to Australia, where Sam’s parents are. And Eugene and Winter and the mysterious man make their way there, as well. Do you start to see why this film is nearly five-hours long, and why it needs to be?

Wenders called this the “ultimate road movie,” and it’s honestly hard to argue with him. The film touches on spirituality, scientific exploration, communities coming together in the middle of an extraordinary moment in time, love, lust, acceptance, forgiveness, mortality, and creative inspiration. The film feels very appropriate to watch right now, in 2020, where people are wrestling with all of those questions and ideas during a global pandemic. It’s not just the film’s ideas that resonate, however; Hurt, Dommartin and Neill do wonderful work in drawing us into these individuals, all of whom make unusual choices, but choices made in a rational manner true to their characters. We understand why Claire goes off searching for Sam, and why they fall in love, and why Eugene eventually lets her go. We understand the allure of what draws Claire and Sam closer, and what might break them apart by the end. We understand the actions of Sam’s parents (played by Max Von Sydow and Jeanne Moreau), and why they draw Claire and Sam in, as the two welcome the exploration of what makes us human. The film Wim Wenders has made is deeply personal, and also profoundly communal. His vision of life at what seems to be the end of the world is intoxicating, and one we should be so lucky to experience for ourselves.