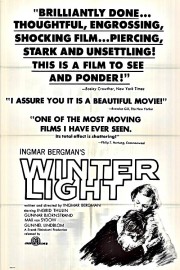

Winter Light

Along with Martin Scorsese, no one has quite looked at matters of faith quite like Ingmar Bergman has. (Maybe Andrei Tarkovsky, but he used it as his subject sparingly over his seven films.) Both filmmakers have made trilogies looking at the mysteries of faith, and the difficulties when God does not put easy answers in our laps. Scorsese’s is a more overt study in faith and religion, with “The Last Temptation of Christ,” “Kundun” and “Silence” forming an easy through line towards one another. Bergman’s, meanwhile, is more subtle, and focused on abstract notions of faith. His “Silence of God” trilogy, as it is called, had three very different stories- “Through a Glass, Darkly,” “Winter Light,” and “The Silence”- but all looked at the nature of God, and his silence in people’s lives, with a sense of purpose and power that is uncompromising, and fascinating. “Winter Light” is the most obviously religious one, and as a result, likely the most powerful.

At some point, I am going to buy these three films, and watch them in the order in which they were made, at which point, I suspect some of Bergman’s common purpose will likely reveal itself. Maybe seeing them in consecutive years, as is my current plan, for my “Movie a Week” series will aid in that, but I know that, in watching Scorsese’s trilogy back-to-back-to-back, that themes revealed themselves that I hadn’t quite noticed before. Bergman, however, was never so linear a director as Marty is, though, thus making connections between films difficult to spot. Pain was a common theme in Bergman’s films, though, and just in “The Silence” and “Winter Light” alone, plenty of that is on display here, coupled with death, and worse, the despair with life. In “Winter Light,” death and despair are intertwined, especially for the country priest, and a member of his flock, both of whom have significant crisis’s of faith, and neither receive much reassurance from God.

“Winter Light” takes place in the span of an afternoon, as one service ends, and another begins. Within those hours take place moments of profound impact on the lives of Tomas Ericsson (the pastor, played by Gunnar Björnstrand) and his small congregation in his village church. We see them take communion from Tomas, and leave for their days, and the pastor retreat to his office. There, he will see three of them, and the conversations they have will set the path of his day. There’s the schoolteacher, Marta (Ingrid Thulin), who is in love with the Tomas, and has let him know on more than one occasion; her advances, which are filled with warmth and longing, are not reciprocated by Tomas, but met with cold, bitter words to go with the flu he is nursing. The other is a couple, the Perssons (Max von Sydow and Gunnel Lindblom). The husband, Johan, is restless after reading about Chinese capabilities with nuclear weapons. Tomas can only offer platitudes to the man, whose pregnant wife is deeply concerned about, but offers to see him for more in depth discussion in half an hour. Johan agrees. In the interim, the pastor reads a letter left to him by Marta, explaining her feelings for him at great depth, with harsh truths intertwined. Johan returns, but Tomas is still unable to offer comfort for the man, and actually reveals his own emptiness with regards to God. Johan leaves the church, and is later found dead, by his own hand, which Tomas must deal with after another encounter with Marta, where he crushes her feelings for him by telling her he is still in love with his wife, who died four years prior.

Bergman’s direction of his actors, and the way he and cinematographer Sven Nykvist compose the shots, is some of the best in his career in this film. These performances are painful and filled with great care for these characters, and what they are going through. The emotions are remote, as they often are in Bergman’s work, but palpable all the same. The story centers around a pastor unable to relate to what he is preaching, and that extends to his flock, with the exception of a sexton who assists in the services. When he talks about Christ’s passion, we feel an innate understanding of what that story represents to a believer. This is the closest to real faith, real appreciation for the sacrifice the Bible says God made for man, that we see in the film. The other characters, Tomas, Johan, Marta, the wife, have stopped being able to comprehend God’s ways. I was reminded of Scorsese’s “Silence” in watching “Winter Light,” wherein the Jesuit priests must reconcile their faith in a land that is hostile towards it. No such balance exists for Bergman’s characters- they cannot hear God speaking to them, and have almost stopped listening, resulting in emptiness and resolution in the idea that God does not exist, or does not care about them. “Winter Light” is cold and stinging, and Bergman makes it painful to experience.