When I planned on going to see Jeff Nichols’s “The Bikeriders” it wasn’t for any of the reasons I’m sure other people had- they’re fans of the cast, interested in the story, or Nichols as a filmmaker- though those things certainly intrigued me. I simply was curious, however, and didn’t have higher expectations for it. Imagine my surprise, then, when I found myself fully immersed in the film’s story, and thinking about it long after leaving the theatre. That’s a credit to all of those elements mentioned above working beautifully in harmony.

The title of this blog is derived from an oft-riffed statement of men doing literally anything to avoid going to therapy. Making a film. Going to a gun range. Getting a sports car during a mid-life crisis. Anything that shifts their obvious emotional issues to something beyond exploring them, breaking them down, and rebuilding their emotional center. The truth is, though, that patriarchal society has chastised men who display any sense of vulnerability. If you start crying, you’re soft. If you don’t fight, you’re weak. If you open up to another man, you’re a wuss. Man’s place is as the main breadwinner and protector of their household; anything else is a sign of emasculation. Often, this would manifest in being called homophobic names as a way of disparaging their masculinity. A man’s worth is in their strength; if they display weakness, they are not worth being called a man. I’m heartened that a lot of generations since mine are seeing past the bullshit notions that society sold men and women about their roles in society, and I think mine- GenX- is helping break those notions, even if we’re a bit late to the party…because for about half of my life, those views were very much something passed down to us.

“The Bikeriders” takes place at a time in the ‘60s when motorcycle club culture was taking hold in America. Inspired by Danny Lyon’s photo-book from 1967, Nichols’s film puts the Vandals MC at the heart of its story. Created out of an impulse to emulate Marlon Brando’s rebellious character in “The Wild One” by Johnny (Tom Hardy), the Vandals are a group of men who love riding on motorcycles like they own the streets, but ultimately feel like a found family for its members to indulge in their masculinity in a way that both feels in step with society, but also out of step with it, as well. Johnny cares about all his members, but the one it feels like he cares most for is Benny (Austin Butler). Benny feels like a loose cannon, and a natural successor for Johnny, but when he meets Kathy (Jody Comer), we get a feeling that he is also adrift in his life. He loves his brothers in the Vandals, but he also wants for a bit more…or less, actually.

The three, distinctive character dynamics at play at the heart of “The Bikeriders” is that of the older father figure (Johnny), the son trying to find his place (Benny), and a woman caught in the middle of all of it (Kathy). Kathy is ultimately the chronicler of the Vandals’s story at its peak, and then during the fall; we see her throughout the film, talking to a journalism student (Lyon’s film stand-in, Danny, played by Mike Faist), and having her as the storyteller gives the film an outsiders perspective we haven’t really gotten in a story like this since Lorraine Bracco’s voiceover in “GoodFellas”. Kathy is uneasy about a lot of things regarding the Vandals, and is a good advocate for Benny to get out when he is almost beaten to death when he refuses to take off his jacket, but we get the sense- especially as she helps Danny fill in the blanks he missed after he stopped travelling with the club- that she sees the value in it for Benny, and the members in general. It was a place for them, apart from society, where they could be themselves, and channel their worst impulses into looking out for one another. In that respect, the Vandals represents an environment that encourages some elements toxic masculinity, but also helps its members embrace a softer side of themselves, and their worldviews, where judgement has no place. (I think this manifests in what we see of the dynamic between Johnny and his wife, and well as Brucie (Damon Herriman) and his wife. We do not get a sense of these men being disrespectful or abusive to their wives, which is a different dynamic that we got from, say, “Sons of Anarchy”, though the same cannot be said of the younger men whom are joining the club in the second half of the film.) As the Vandals break up, our ideas of motorcycle clubs as violent, lawless gangs that serve no positive purpose for society takes over, but in Kathy’s voice, and Danny’s engrossment in the culture, the potential of what the club could offer men lives on. Seeing Benny’s fate, we get a sense of something lost in the violence of people who only looked at what the Vandals were, and saw an entitlement to rebel against the world for their own sake, even if it meant leaving their friends behind. But Benny is content, and seems to be in a better place than he was at the beginning of the film.

This is not to say that Nichols is advocating for motorcycle gangs as a positive to society to be brought back; I think he sees the value they had in the moment of history this film takes place. What Nichols, I think, is advocating for is an understanding that sometimes, men feel out of step with society’s desires for them, and finding a home among men like them is not inherently a bad thing. Therapy or a support group could help them, to be sure, but some men are still uncomfortable with the idea of that type of communication; it’s more important that men find support from one another in their own way. I know that, for a long time, I was uncomfortable with the idea of therapy, until I knew I needed to get past that. But even then, I’m grateful I’ve had my share of male friends I felt like I could confide in, without judgement, who could help me grow. This is where “The Bikeriders” took me, and I did not expect it to. I never wanted to be part of a motorcycle club, but the sense of community, and understanding, it shows for these men- and how they mostly thrive as a result- connected with me profoundly.

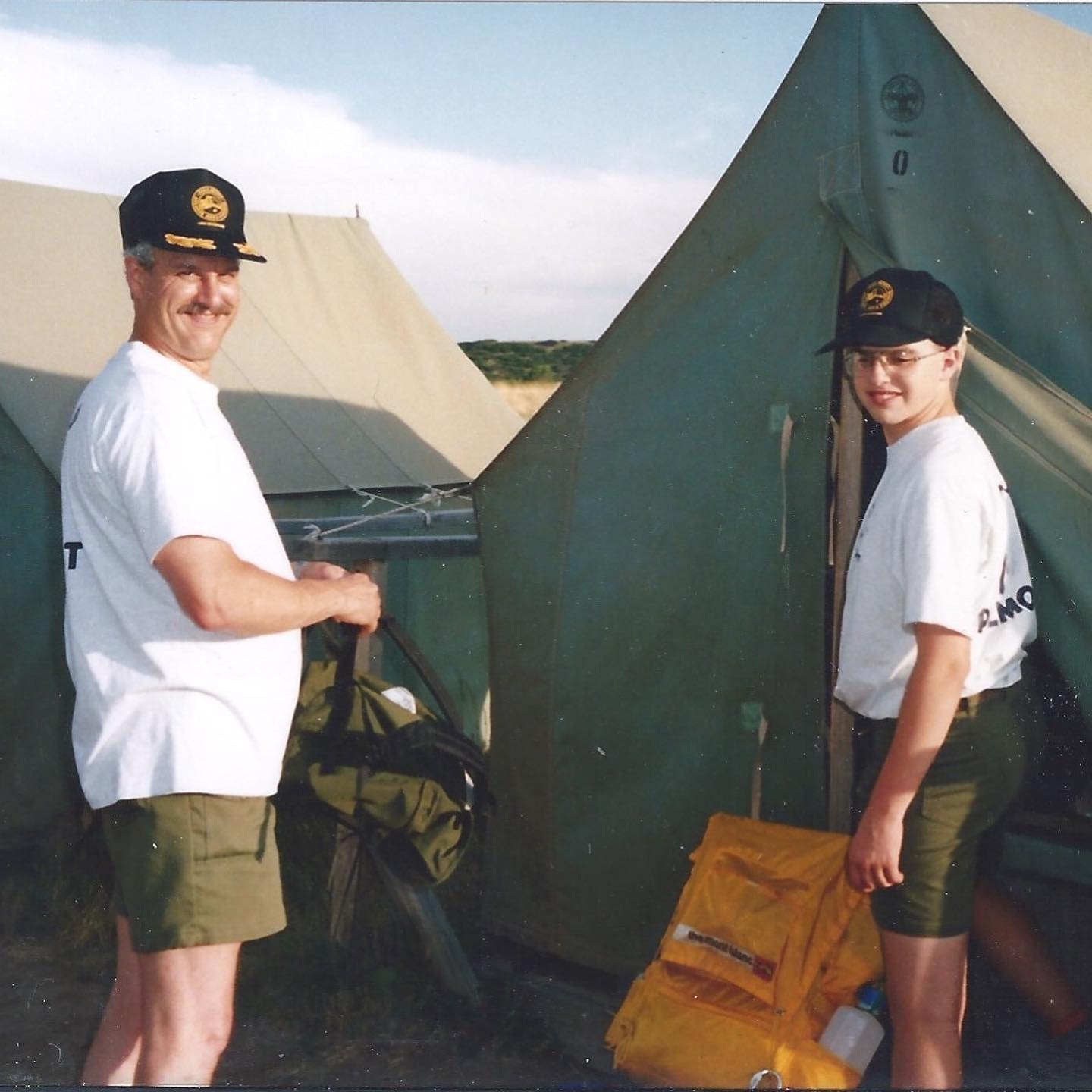

The more I think about this film, I think it’s one my dad might have connected with. He was not the movie lover my mother and I were, but we could occasionally get him to watch something. (At home, anyway. The last film he saw in theatres was “Saving Private Ryan” in 1998.) He would have been of the generation that comes up in the tail end of the film, but I think he was closer in spirit to the men like Johnny and Benny. He was never a member of a motorcycle club; the closest equivalent he had was being a member of River Bend Gun Club after we went up on a Boy Scout trip. In addition to shooting in matches, he also ran matches on the weekends and became an important person at the club. He was someone who immersed himself in his work, and his love of the gun club, and didn’t really share much of himself with me and my mother. For him, River Bend was a place besides home where he felt comfortable, and felt like he could be himself. When he died in 2013, we had several of his friends from the gun club reach out and tell us how much he meant to them. It took a lot of his time away from us, but I’m glad he had a place he could go, and connect with other people. Having a home away from home is important; seeing this film on his birthday doesn’t feel like a coincidence.

Some men would rather do anything other than go to therapy. For many, that might be more important to finding purpose in their lives. It means they’re finding their independence from society’s wants, and embracing their passions.

You can read more about my thoughts on mental health, and my love of film criticism and creating at an interview at Bold Journey here.

Thanks for listening,

Brian Skutle

https://www.sonic-cinema.com