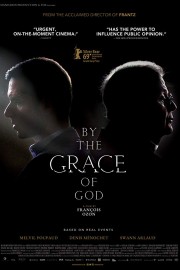

By the Grace of God

As it began, I couldn’t help but wonder how Francois Ozon was going to turn the story he’s telling in “By the Grace of God” into a compelling, 137-minute drama. That wasn’t a reflection of the true story he was telling, but his approach in telling it, which felt dry and fairly one-note. And yet, it continues to build into a riveting character piece on the ways people cope with abuse, and how they challenge an authority that does not appear to have their best interests at heart. This is quite an experience by the time the film reaches its climax.

It’s weird to say, but I began with the film thinking, “Well, how much more can be explored in film with regards to the history of abuse in the Catholic Church?” Between documentaries and films like the Oscar-winning “Spotlight,” hadn’t all of the key points been explored? “By the Grace of God” has a heartbreaking story to tell, however, one that has three men, each with different trigger points, that bring their painful pasts into the light. It is a slow-burn that grows into a rage against the silence and complacency of the Church in the face of its greatest sin.

The film begins in 2014, just as Alexandre (Melvil Poupaud)’s two oldest sons have begun to become active in the church. He begins to have memories of sexual abuse he dealt with at the hands of Father Bernard Preynat (Bernard Verley) when he was in scouts as part of the Church in the 1980s. As he reveals his secret to his family, he attempts to confront the Church about the abuse, and he is given a mediated meeting with Preynat at the behest of the local Cardinal, Cardinal Barbarin (François Marthouret), and though Preynat acknowledges the abuse to Alexandre, he does not ask forgiveness of it. That is the sticking point for the Church, and though Alexandre is told Preynat will be removed from a parish, seeing him working with boys angers Alexandre, and he files a police complaint against Preynat (the statute of limitations for criminal charges has long passed). The complaint leads the police to François Debord (Denis Ménochet), whose family had tried in vein to have Preynat punished for abusing Francois as a child. The memories come back, and Francois, now an atheist, wishes to hold the Church accountable, and forms a group for victims that he hopes will pressure the Church into reforms in how it treats victims, and punishes those whom abuse children, and cover it up.

There is a third character that takes focus in the film, and he is also a victim of abuse; his memories come flooding back when his mother shows him stories of the work Francois’s group is doing. The character is Emmanuel Thomason, and his abuse falls within the statute of limitations for criminal charges. He is played by Swann Arlaud in the film’s most affecting performance. Though we feel the weight of the abuse of Alexandre and Francois, we see the consequences of it in Emmanuel’s life, and understand how, when tied into the divorce of his parents, we see how the added trauma led to the broken man he is now. His actions in the film are the most courageous, as we see him look at himself, confront the truth, and begin to heal. One of the things that Ozon does so beautifully is witness these three men, each of whom have different journeys in to the fight against the Catholic Church, and see how each one almost builds off of the efforts of the other to build to where the film ends. That’s how it distinguishes itself, and why it left an impression on me. It haunts and inspires as Alexandre, Francois and Emmanuel confront their pain, and the people who caused it, head on, aware that it’s an uphill fight. By the grace of God, though, they will bring about change, no matter how long it takes.