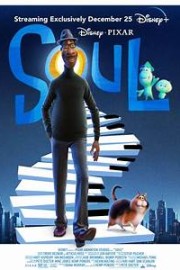

Soul

The worst thing we can do in life is live it waiting for something that may, or may not, happen. To do so deprives us of our most precious gift- life itself. Experiencing it, feeling through it, being hurt by it, and being excited at the unexpected pleasures. For his fourth feature film, Pete Doctor goes fully existential, and while he cannot quite reach to heights of “Up” or “Inside Out,” he still hit all the right notes in me with his music-heavy “Soul.” I cannot say I am surprised.

Joe Gardner (Jamie Foxx) is a music teacher who has wanted to follow in his father’s jazz musician footsteps since he was a kid. His mother (Phylicia Rashad) is hesitant to support him, not because she doesn’t love him, but because she doesn’t want him to struggle with the life like his father did. On this particular day, though, he gets his chance when a former student offers him a chance to sit in with The Dorothea Williams Quartet. He’s on Cloud 9, and after the audition, he is jazzed for what awaits for him that night. He’s not very careful, though, and he falls down an open manhole in the street. Next thing he knows, he’s a soul floating to The Great Beyond. He can’t be, though; he still has so much left to do. He finds himself in a part of the ether where souls are trained to go to Earth, and he ingratiates himself as a “teacher.” When he is mistaken for a great child psychiatrist, and assigned a potentially hopeless case in 22 (Tina Fey), though, his road back to his body is overly complicated.

Before I get to anything else, we need to discuss the music in this film. Because Joe is a jazz pianist and music teacher, you know the music is going to have to be a key component of this film. But rather than go with Michael Giacchino, as he did with “Up” and “Inside Out,” Doctor brought in jazz composer Jon Batiste (who is Stephen Colbert’s late-night band leader) to write the jazz pieces and arrangements for when the movie is in New York, and Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross to write the music for when the film is in The Great Beyond. If you had told me Reznor, the front man of Nine Inch Nails, would ever write music for a Pixar film in 2000, I would have told you that you were crazy, but here we are, and honestly, the juxtaposition between Batiste’s contributions and those of Reznor and Ross is not as jarring as you would expect it to be. As we see in the early minutes of “Soul,” jazz is so much about feeling out what fits within a basic framework of a piece of music, and really, the way Reznor and Ross have scored most of their films seems to work in a similar manner- what distinguishes Batiste and Reznor/Ross is simply the sonic landscape they are working in. I can see myself, once this soundtrack becomes available, listening to it and just getting swept away by the emotions it brings out of me, and there were plenty.

In a way, “Soul” reminds me of “Mr. Holland’s Opus,” and while that probably sounds like a painful experience for a lot of people, it’s not as overly sentimental or sappy as all that. Along the way, Joe learns a lot about himself because of something that happens when he looks to be able to get back into his body, and he sees himself from an out-of-body perspective. For a lot of the film, it looks like, just as with Mr. Holland, the lesson for Joe will be that his real gift isn’t the music he creates, but the people he inspires to perform, but it’s not quite as simple as that here. This movie is about finding your true path in life, but Doctor and his collaborators (namely, co-writers Mike Jones and Kemp Powers, the latter of whom is credited as co-director) are not wanting to lock down a simple answer as you are destined to do one thing over another as an occupation. That’s something that, when we’re young, we find ourselves feeling- we try to lock ourselves into one, specific thing we’re supposed to be doing in our lives, and if we aren’t that, we are a failure. Society puts that pressure on us, as well, and it can lead to a lot of anxiety as we grow older, and seem further away from what we wanted to do, if we don’t achieve it naturally. As someone who knows what that was like, I also know that, once I realized the faults in how societal pressure works against us, I felt freer to be content to simply live, and see where that leads me, than when I felt like I had to hit a specific checkpoint at a certain time of my life. That’s the ultimate message of “Soul,” and I love the way it’s presented here.

While I’m grateful that people will be able to watch “Soul” safely, from the comfort of their own homes, for the first time, as it’s being released in the midst of one of the worst parts of this global pandemic, it’s heartbreaking that this will not be able to be experienced in a theatre for the first time. As can be expected by Pixar, and especially Doctor, at this point, “Soul” is a beautifully animated film, and The Great Beyond might be one of their richest visual landscapes yet. Similarly, the soundtrack would be a wonder in a theatrical sound system, and I hope that maybe, when things have settled down, Disney gives this a theatrical release so that audiences can experience “Soul” the way it was intended. Regardless of how you see it for the first time, though, “Soul” will capture that spark we have in all of us, something Pixar always feels acutely confident in can reach, and make us feel like we’re ready to live a little better, a little less anxious, afterwards. I’m always supportive of that goal in art.