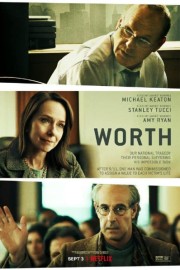

Worth

As I watched “Worth,” I couldn’t help but think of Ron Howard’s “Gung Ho.” That’s a weird comparison, but in both movies, Michael Keaton plays a character whom a community is counting on to deliver them some relief from the struggles of life. Both play to an ethos of doing what’s best for people over themselves, and we see that in his roles in “Spotlight,” “The Paper” and even his self-righteous villain in “Spider-Man: Homecoming.” The difference is “Gung Ho” is trading off of Keaton’s cock-sure youthful charm, and in “Worth,” his Ken Feinberg is more soulful, trying to stick to his guns, even when the process gets muddied by emotions. Eventually, both characters get to a point where how they approached their roles needs to change for them to find success. The measure of Keaton’s talent is that he makes each one comes off as authentic.

I did not lose anyone of September 11, 2001. I cannot imagine what it was like for the people who did. When Hollywood has approached the topic, it’s been a minefield of different attempts, but the best films have put away conventions, and gone for brute honesty and heart. Sara Colangelo’s “Worth” approaches some of the stories of those who lost people with empathy, even if the main character is someone whose job it is to put a number on their suffering. Feinberg is in charge of the 9/11 Victims Compensation Fund. We don’t envy him the task in front of him.

The screenplay by Max Borenstein sets the film’s dilemma in its early scenes. Feinberg is teaching a class at Georgetown. He specializes in legal proceedings involving victim compensation, and an exercise he gives his class makes it seem like a clear-cut situation. When he is assigned to be Special Master in charge of the disbursement of funds for the 9/11 Victims Compensation Fund, he figures he’ll work out set amounts for people based on their earnings, with an impersonal mathematical formula that will take out guess work, he’ll get his 80% threshold of people to join in, and that’ll be that. As he and his team- including Amy Ryan as Camille Biros and Shunori Ramanathan as Priya Khundi- get to talking to victim’s relatives, there are nuances that arise that don’t seem to fit within their parameters. He has two years to get people to sign on, but outside forces, like a fellow lawyer (played by Tate Donovan) who’s trying to make sure his wealthy clients get theirs, and an advocate (Charles Wolf, played by Stanley Tucci) who finds problems with Feinberg’s impersonal approach, seem to want to challenge him at every turn. If he changes things mid-stream, though, he threatens his ability to get anything for anyone.

Sometimes, our own desires get in the way of what’s right. A key moment is when Feinberg meets, one night, with the widow of a New York fireman, who just wants her husband’s story in the record. She doesn’t want any money from the fund; she just wants to move on. We’ve seen her brother-in-law, also a fireman, advocate for her; he wants his brother’s memory preserved. While this meeting itself isn’t a flashpoint for Feinberg to shift his approach, what is revealed afterwards is, and points to how complicated the process of compensation in any case is. We get scenes with immigrants whose status is questionable, and a poignant story of a gay man whose partner died in the attacks, but- because they weren’t legally together- the victim’s homophobic parents would get the compensation. They can only do so much, though, if the law isn’t on their side. These are some of the questions that they have to weigh, and why a simple formula does not work.

Colangelo’s film is ponderous but effective in giving us a way into an intellectual process through emotional narratives. Wolf is a counterpoint to Feinberg, but he’s not really an antagonist; he’s basically Feinberg’s conscious in the film, trying to lead him away from thinking about this purely through financial and intellectual prisms, and more as a human being. Is their a price that could possibly be fair for all? No. Will there be any amount of money that will ease the emotional pain? No. Wolf understands that, and seeing how he, gradually, attempts to nudge Feinberg in his direction as opposed to constantly getting in his face about it shows a patience and understanding about Feinberg that comes through beautifully in Tucci’s performance. He and Keaton are the heartbeat of this film, and seeing them eventually meet at the same place is inspiring, and hopeful that understanding, and compassion, are not lost in people who come from different backgrounds. That’s ultimately “Worth’s” worth as a film.