Nothing Compares

When I really started to dive into contemporary music in the early ’90s, I focused on the rock bands like Guns N’ Roses, U2, Nirvana and Pearl Jam, while also getting into earlier artists like Pink Floyd, Jimmy Hendrix and Bruce Springsteen. Even though I was a rabid MTV viewer, Sinead O’Connor was not on my radar. The name was familiar, though, especially when it came to the controversy that surrounded her. And then, when I got into film music, I left most of the other genres behind, save for soundtrack albums. By that point, however, the larger music industry had left O’Connor behind, though; she’d burned too many bridges with her outspokenness.

Music has always been the best creative outlet, I think, for protesting against power. What’s profoundly ironic is that, in America, the generation that, arguably, best exemplified that spirit- the Baby Boomers- is the one that, when people like O’Connor and The Dixie Chicks took a stand for what they thought was right, they were the first ones to call for boycotts. Even if it was the acts of defiance of them, they’re also the generation that chastised rap, and made sure the “Parental Advisory: Explicit Lyrics” label was on any album with a dirty word on it. It’s truly baffling, but when you become the ruling class, I guess you set the rules. O’Connor was one of the artists most impacted by that.

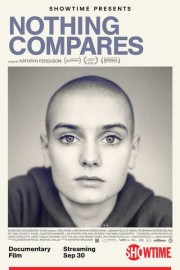

“Nothing Compares” looks at the early part of O’Connor’s career, and the life that shaped her as an artist. Born in Dublin, she was rebellious as a child, so much so that she ended up in a Magdalene asylum (a “Training Centre”), where her love of music developed, but she also faced consequences for continued non-conformity. Her mother died in 1986, and was the source of much abuse growing up before she left to live with her dad at age 13. At 21, she released her first album, and a meteoric rise in stardom for her fresh sound and look (including a shaved head) began. The Prince-written single, “Nothing Compares 2 U,” took her to another level, but it was short lived. As her profile rose, so did her outspoken nature; refusal to play if the national anthem was played at a venue, and then- of course- tearing up a picture of Pope John Paul II on “Saturday Night Live” as an indictment of sexual abuse in the Catholic Church. At that point, all Hell breaks loose, and the controversies build from there.

Director Kathryn Ferguson doesn’t show O’Connor, who changed her name to Shuhada Sadaqat to go with her conversion to Islam in 2018, in the present day until a performance at the end of the film, though we do hear her voice throughout, as well as the voices of friends, managers, publicists from that early time in her life. What’s striking about “Nothing Compares” to someone who was not really conscious of O’Connor at her peak is how it puts us in the moment while also being a chronicle of that time. We feel that sense of need to speak out build in her with every word she says, and understand why it happens. We also see what she led the way for, as more and more female artists especially have been emboldened to speak out in her wake, and been more celebrated than she was. Truly, the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice, or in O’Connor’s case, vindication. All the while, she has continued on her own path, and continues to be a model of rebellious art.