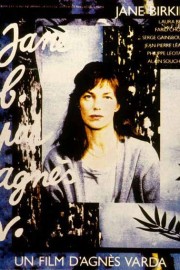

Jane B. for Agnes V.

One of my favorite films from Orson Welles’s is his 1974 movie, “F for Fake.” In that film, he pulls back the illusion of realism in cinema to make something personal about the hustle, and a hoax, which is basically a fundamental truth in cinema- filmmakers are always hustling for finances (something Welles knew all too well, at the time), all in the service of pulling off a hoax against the audience. Agnès Varda’s “Jane B. for Agnes V.” is similar in that it puts the director onscreen as a way of telling a story about filmmaking, this time focusing on the life of an actor. The actor in this film is Varda’s longtime friend, Jane Birkin. For a year, as Birkin turns 40, Varda’s camera watches as Jane reveals herself through scenes, monologues and probing discussions with the director. Here, Varda is revealing the insecurity behind the performer, and the truth behind the lie that is a screen performance.

I find myself endlessly fascinated by movies that don’t just portray the filmmaking process, which can be fun and insightful, but ones that make choices that allow us in on the secret that we are watching artifice. The beginnings of “Hour of the Wolf” and “Mirror” do this, as does choices Bergman made in “Persona.” While yes, we do not need a reminder that what we are watching is a fiction put on film, the audacity of a filmmaker making deliberate choices to let us in on that as we watch a movie is exciting. A bit pretentious? Perhaps, but it also speaks to the confidence these filmmakers have in their process. Varda is doing something similar, but rather than subverting the artifice of a narrative fiction, she is pulling the curtain back on documentaries, showing that while the person in front of the camera is an authentic individual, documenting truth is as much a work of narrative trickery as anything in “Vagabond” or “Cleo from 5 to 7.”

From the very beginning, we are transfixed by Birkin onscreen. We hear her talk about insecurities of being on camera, with Varda noting that she doesn’t really look directly at the camera. We see Varda’s camera, and sometimes the director itself, in the frame, whether it’s in the reflection of a mirror or window, or deliberately. We see her and Varda play a Laurel and Hardy scene together; we hear Birkin tell a story of an innocent encounter with a 14-year-old boy in a hotel; we see moments of a staged picnic Varda between Birkin and Jean-Pierre Léaud, as well as scenes recreating works of art. One of the best moments in the film is when Birkin is singing a song, and discussing Marilyn Monroe; the way Varda shoots it is incredible sweet and sensual, but not exploitative; she couldn’t be exploitative if she wanted to be. All through the film, however, is a narrative of a woman looking at her life, reflecting on her work, and realizing what she wants to be moving forward. The even year birthdays- especially the ones ending in zero- have a way of doing that to you. Varda captures that beautifully in a film that is filled with artifice, but gets to a truth in a way only film is capable of achieving.