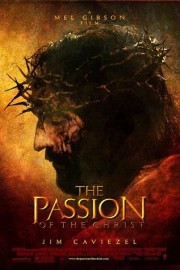

The Passion of the Christ

Originally Written: April 2004 & January 2005

Is “The Passion of the Christ”- or Mel Gibson- Anti-Semetic? No.

Is “The Passion of the Christ” “the most violent movie I’ve ever seen,” as Roger Ebert said? Yes and no.

Does “The Passion of the Christ” go too soft in characterizing Pontius Pilate? Yes.

Does “The Passion of the Christ” go too far in vilifying the Jewish High Priests? Yes.

Is “The Passion of the Christ” “as it was,” as the Pope has been quoted- and denied- as saying? How would I know? I wasn’t there.

Is “The Passion of the Christ” perfect? No.

Is Mel Gibson perfect? No.

Is Mel Gibson an artist? Yes.

Is “The Passion of the Christ” art? Yes.

It was going on two months that I began to write this since I’d watched “The Passion of the Christ” for the first time (I’ve since seen it again), and I’m still no closer to figuring out a good way of discussing the movie. So instead of a “good way” to discuss the movie, I’m going to find an “honest way” to discuss the movie.

In all honesty, I read too much. From the moment I heard the announcement back in September of 2002 when I heard Mel Gibson- a favorite actor of mine and underrated director- was spending his own money to co-write and direct a film about the last 12 hours of Christ’s life in Latin and Aramaic- with the original intent to avoid subtitles- I was immediately enthralled with the project. And then, the controversy started, and I soaked it all in (OK, not all of it, but a good deal of it), and it made me want to see the film even more. Had Mel created a masterpiece, or was it the worst mistake of his professional career? I wanted to find out.

In all honesty, I can’t look at the film through a lifetime of religious upbringing as some who are reading this can, and I won’t pretend to. When we first moved down to Georgia in 1988, one of the things my mother and I did was join the local Presbyterian church. I went to Sunday School for most of my first seven years living in Georgia, and attended services. But as my school schedule my final year of high school and college grew more demanding, I just stopped going. It’s been years since I’ve read either the Gospels or any of the Bible. This isn’t to say I’m a non-believer; I guess the best way to say it would be that my beliefs are not as strong as others are. I would consider myself a spiritual person, though that spirituality isn’t rooted in one particular belief structure.

That said, over the past few years- as my preferences in movies have shifted from action-packed spectacle to more thoughtful, personal expressions, and my ideas of what makes a good- or even great- movie have deepened, some of the most rewarding films I’ve seen are religious- or spiritually-themed- films, and in many cases, the more controversial ones. Those I treasure most highly are Martin Scorsese’s indelibly moving “The Last Temptation of Christ”- another venomously-debated act of faith whose controversy (16 years later) has survived to this day; Scorsese’s profoundly underrated “Kundun,” the poignant story of the Dali Llama and his eventual exile from Tibet; Kevin Smith’s reverent and funny “Dogma”- a potty-mouthed comedy with purpose whose detractors can clearly not look underneath this thoughtful story’s vulgar surface; and above all, Andrei Tarkovsky’s artful, daring epic “Andrei Rublev,” a provocative and rewarding examination of the relationship between art and faith as it relates to the famous 15th century Russian icon painter whose work has long been considered the standard by which all others should follow. The reason I hold these above other like-themed films? I find they have given me more to think about in the subjects they explored than other, safer films.

In all honesty, this is going to be a look at the film as a film. As art. I can’t look at it any other way; at least, for now I can’t. As I’m writing this part of my review, I’ve only seen the film twice- hardly enough for me to have the full impact of the film on an emotional/spiritual level sink in. However, do not think it won’t in the future. In 2000, when I first saw Edward Norton’s thoughtful comedy “Keeping the Faith,” I felt it was a good movie, if not a great one. When I saw it again, however, the meaning of it for me changed, largely because the context of how I had seen it had since changed (it was at the time I was in Ohio visiting my dying grandfather when I saw the film again). I now consider it among my favorite films of all-time. A better- and more fitting- example still is Steven Spielberg’s “Schindler’s List.” When I first saw that indelible milestone, I saw the greatness as filmmaking immediately, and looked at the film strictly through the prism of news media “hype” of the film as “the film that would finally win Spielberg an Oscar.” It wasn’t until I watched the film again- my third time- when it made its network television debut in 1997 that the historical importance of the film, and emotional power of the story, was truly felt. That is what to expect from this review. For now, I can only look at “The Passion of the Christ” as a work of filmmaking, and attempt to address the film’s worth in perspective of the overwhelming hype and controversy its followed. I may be able to address the film on a more personal level in the future (in fact, I’m pretty sure I’ll be able too), but that could be as soon as my third viewing, my next listening of the soundtrack, or as distant as a future viewing maybe years from now. For now, though, the thought I’ve experienced above all else in regards to “The Passion” is analytical, and that is where this review is coming from. It’s now time to begin that thought in print.

When put in context of the other films Mel Gibson has directed- 1993’s undervalued “The Man Without a Face” and 1995’s beloved Oscar-winner “Braveheart” (which still sits #2 among my favorite all-time films)– a main theme runs within the three films. It is found in the main characters; all three (“Man’s” Justin McLeod, “Braveheart’s” William Wallace, and “The Passion’s” Jesus) are seen as threats to the establishment or rules of the societies they lived in. To say Gibson simply has a Martyr Complex would be too simple-minded; all three are inspiring characters- McLeod for his thoughtful wisdom and brave acceptance of what life has handed him; Wallace for his old-fashioned heroism and courage; Christ for his profound sacrifice. If I didn’t know as much as I do about Gibson as a person from interviews, I would still be able to guess the personal importance of bringing these three lives- two of which are historic, while the third is the product of fiction- to the screen. Gibson’s passion for these stories is evident in every frame.

Does that mean Gibson’s made nothing but masterpieces? No. “Braveheart” is easily his best film, with no scenes that could be removed and none of the pretentious but well-meaning directorial heavy-handedness that hold both “The Man Without a Face” an “The Passion of the Christ” back from true greatness, which leads me to my first talking point on “The Passion”– Gibson as director. Honestly, some scenes rank among Gibson’s best in his brief directorial career. The powerful opening passages in the Garden of Gethsemane come first to mind, as Jesus is tempted to renounce his Father’s purpose for him by Satan (who taunts him, saying that no one man can carry the burden of a world’s sins), then betrayed by Judas and arrested at the hands of Jewish soldiers who lead him to the Sanhedrin. Immediately we see the poetry of cinematographer Caleb Deschanel’s painterly images, many of which are inventively and indelibly filmed in slow motion (“Passion” is the best use of the tired process since John Woo’s Hong Kong masterpieces and Gibson’s own “Braveheart”), and hear the haunting emotion of composer John Debney’s score. When married together, Deschanel’s cinematography and Debney’s music– both equally overwrought in their artistic approach to the material (lacking in the subtle power that has stayed with me from Tarkovsky’s “Rublev”) –bring a hallucinatory quality to Gibson’s film a more subtle approach would have lacked, heightening the drama and startling impact of the story.

For Gibson’s vision of the story, this is the correct aesthetic to convey the raw emotional truths at the heart of the “Passion” according to Mel. Few filmmakers have shown such audacity and artistic daring; the most immediate example for me is Steven Spielberg’s ambitious and deeply-felt approach to “A.I. Artificial Intelligence.” Of course, few filmmakers have had a story that’s touched them to the core as plainly as the Passion does for Gibson. Every shot (however pretentious at times), every scene (however unnecessary or ill-developed at times) is vivid and unforgettable, at best for their beauty- however brutal, at worst for their bombast- however unintended. The scourging at the pillar- a sequence of paralyzing intensity in which Roman soldiers flay Jesus’s skin almost to the bone as onlookers (including the Jewish high priests who seek to condemn him, Jesus’s mother Mary (indelibly embodied by Maia Morgenstern) and Mary Magdalene (Monica Bellucci))- is filmed with numbing power and empathetic compassion. The march to Golgotha- with Jesus further brutalized by the Romans as he’s forced to carry his cross to the mountain of his Crucifixion- is harsh and brought to mind two rigorously unsentimental, but deeply powerful, moments from “Schindler’s List,” one when the workers in Schindler’s factory are forced to shovel snow instead of going to the factory, and when the Jews are being lead out of town, and forced to endure the taunts of the crowd. But never is this truer than in the closing frames of “The Passion,” which portrays Christ’s Resurrection with a reverential awe and grace that’s as inspiring as the act itself.

The violence. In terms of the duration- in comparison to the film’s running time- that the violence goes on, this is, indeed, the most violent film I’ve ever seen, as it’s almost relentless to watch at times (the scourging in particular will have a devastating effect). In terms of the brutality, only the scourging- for me- holds the unsentimental rigor of a “Saving Private Ryan” or “Braveheart” in its’ depiction of onscreen brutality. That sequence alone would earn any other movie an NC-17, and maybe it should have earned this one that rating (however deep your religious convictions, no one under- at worst- 13 should be subjected to the violence here). However, the blood and bruise makeup effects- so effective- makes the constant beatings and whippings Christ takes at the hands of the Roman and Jewish guards seem much more violent than they really would be without the makeup. That doesn’t make it any easier to watch, though.

The charge of anti-Semitism, and “The Passion’s” ability to cause anti-Semitism. At the risk of offending anyone who had a deeply emotional experience at “The Passion of the Christ,” no film (not even this one), no play, no form of art of any kind, is capable of such a profound reaction as to convince a viewer or group of people to hate another. I’m not anti-Semetic. While in Gibson’s depictions of the Jewish Priests- and the exceedingly sympathetic portrayal of Pilate- I can see where the flames of anti-Semetic behavior and feelings could be fueled, I did not come away from “The Passion of the Christ” with such feelings, both in myself, nor did I feel Gibson was anti-Semetic. I even got a sense in some moments of “The Passion”- on the hill of Golgotha, and during the scourging- that Gibson showed some remorse on the parts of the Priests. Maybe I’m the only one who felt that way (maybe I’ve just seen too many movies with such moments), but in those moments, and in the moments as Christ is carrying the cross when Simon is brought out of the crowd to help him carry, and at first he’s reluctant, only to grow more sympathetic of Christ’s burden (one senses in Simon’s face as he goes down the hill an understanding of what Christ is carrying that cross for), and when a woman- also from the crowd- tries to bring Christ a cup of water after he’s fallen, I felt I saw the truth of Gibson’s own beliefs lying underneath the controversy.

That the film has generated such a heated debate is hardly shocking. Like D.W. Griffith- whose “Birth of a Nation” (the most blatently racist film I’ve ever seen) is still a lightning rod for controversy 90 years after its’ release- Gibson as an artist is- in a way- a victim of his material. He wants to tell the story that’s inspired his imagination, and he felt compelled to tell it as he read it. As the director, he could choose what he left in and took out, but it was- for him- an unavoidable and vital part of the story to include the Sanhedrin trial, to sympathize- to an extent- with Pilate, to show the venomous nature of the Jewish crowd, calling for Christ’s crucifiction, even going so far as to include the controversial line from Matthew where the Priests say, “His blood be on us and on our children,” a line which is still spoken in the film, but excised from the subtitles. However, unlike Griffith (who didn’t try to counter the racism in “Nation” with a balanced look at the freed African-Americans (which makes the film hard to watch, but oddly, truthful given the time it depicts, and the time it was made); he would atone for it in his next film, the astonishing “Intolerance”), Gibson does counter this slanted look at the Priests- who, it should be noted, also seem to hold positions of political power and are looking to appease the Romans, as well as themselves- with kind Jewish characters, including- it should be noted- Mary, Mary Magdeline, Christ’s deciples, and Christ himself. Some might say he’s appeasing his critics, but since such characterizations are inherent in the story, it would be hard to argue the point. Like “Nation,” this was the film Gibson wanted to tell, the story he wanted to tell. Take it or leave it.

I have now seen “The Passion of the Christ” three times now. The first was the first Sunday it was in release. The next time was two months later, as I tried to get a start on this review. The most recent time was a Monday in January of 2005 on DVD. This last time afforded me an opportunity to see “The Passion” in the way Gibson originally intended, which was sans subtitles. The idea was one of the reasons the film intrigued me when it was first announced.

And what did I find? I found that while the temptation to turn on the subtitles is high (hey, we’re just conditioned to have them, aren’t we?), the emotion of the movie comes through with stunning clarity- as perfect an argument to return to the time when silence was indeed golden- ie. the Silent Era of the early 20th Century- as I’ve seen in any contemporary film (though the dialogue of “Titanic” and “Star Wars: Episode I” makes the argument as well). It’s a tribute to Gibson’s filmmaking vision, Descanel’s haunting cinematography, and Debney’s bombastically beautiful score that the story- so well known- doesn’t need words to be told. Of course, seeing it twice before with subtitles no doubt helps. But anyone who’s seen- and loved- “Braveheart” and “The Man Without a Face” will tell you that Gibson doesn’t always need dialogue to be a great storyteller.

As I close this review, what do I think of “The Passion of the Christ?” I think it is a flawed work of art. I think some of the visual effects- be it as subtle as the manipulations of faces to give them a demonic look as Judas is tormented by kids to suicide (which look false) or as obvious as a raindrop falling from Heaven when Christ has finally died on the cross (which feels exceedingly pretentious- and an overhead shot of a defeated Satin- who is ever present in the film- in the depths of Hell after the temple crumbles (which was unnecessary) make it flawed. For me, all were unnecessary to get the point of the story across; without them, the film would indeed be a masterpiece. But the moments of haunting poetry- be it brutal or beautiful- throughout the film- and there are many- make it art. The opening shots in the Garden. The grace notes of emotion in the form of flashbacks- brilliantly integrated throughout the film- presenting context and a deeper emotional connection to Caviezel’s battered Christ. The moments of pain and poignancy on the cross. And the final scenes when the great miracle of salvation is complete. Just some of the moments in which Mel Gibson aims for transcendence and a deeper emotional connection with a story that means so much for him…and succeeds.