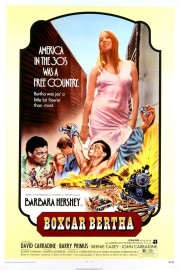

Boxcar Bertha

Now that I’ve seen a film by pre-“Mean Streets” Martin Scorsese, I’m curious to see his other work, before he became a legendary chronicler of crime and guilt. Produced by Roger Corman, “Boxcar Bertha” is unlike any other film I’ve seen from Scorsese. The visual style that would become his signature is not yet polished. The theme is survival rather than the Catholic guilt and violence that pervades his great classics. The one thing that is a common denominator between this film and the likes of “Taxi Driver,” “Raging Bull,” and “The Last Temptation of Christ” is the natural feel of the performances, which give the film a documentary feel that has always distinguished Scorsese’s best films from those of his contemporaries from the ’70s.

The film is based on a true story of the Depression, when a young woman (Bertha, played by Barbara Hershey) goes on the road with a union leader (Big Bill Shelley, played by David Carradine) after the death of her father. Gradually, the two become criminals in order to make their way across the South.

That’s really all there is to the story in this 88-minute flick. Working with Corman was a profound inspiration for the young Scorsese, and that method of fast filmmaking and faster, economical storytelling has stayed with the director throughout his career. Admittedly, the economy of his storytelling has diminished in his later years (most of his films the past decade-plus have pushed two hours-plus), but the urgency of his direction remains just as vital as ever. One of the most intriguing elements of the story in “Bertha” is the frustrations Big Bill have with the direction his life has taken. A proud union man, he feels genuinely unsettled by what his actions have done to his reputation as an upstanding, hard worker. Still, he recognizes the necessity for crime when society fails the working man, although he easily gets offended when it’s implied that all he is is a criminal.

It’s the search for identity, for what truly defines these people, that intrigues Scorsese the most in “Boxcar Bertha.” And in a way, that’s a common thread throughout just about every one of the films of his I’ve seen over the years (the exception is “Cape Fear,” Scorsese’s most blatant genre effort). It drives the criminals of “Mean Streets,” “Taxi Driver,” and “GoodFellas.” It nags at the psyches of Jake LaMotta in “Raging Bull,” his Christ in “The Last Temptation of Christ,” and the Dalai Lama of “Kundun.” And it haunts the cops and robbers of “The Departed,” the lawman in “Shutter Island,” and the young boy and old magician in “Hugo.” Even when she’s apart from her love, Big Bill, Bertha is struggling for a sense of self that leads her down some desperate paths, and Hershey nails every nuance of the roll. The thing that surprised me most watching “Bertha” is how, despite its cosmetic differences with Scorsese’s other films, deep down, it is very much in line with the great director’s interests over his 45-year career thus far.