Proof

Catherine is a broken person. For the past five years she’s been tending to her father Robert, a brilliant mathematician whose mind has suffered a break from reality. For several months three years ago he had a period of clarity, but otherwise, he has been but a shell of the man he once was. Her sister Claire means well, and has been paying off his house from New York, but she has distanced herself from the day-to-day care unlike Catherine. Herself a promising mathematician, Catherine makes personal sacrifices- like dropping out of Northwestern- to care for the man whose professional path she’s following, although she dreads also in following the personal one he took as well. When we first see her, she and her father are having a discussion in which her father says that crazy people don’t ask themselves if they’re crazy. When Catherine asks him about this, he replies, “Aren’t I dead?” He passed away a week ago; the funeral is the next day.

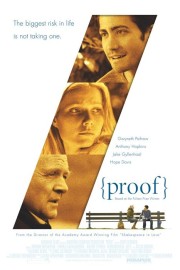

“Proof” is about many delicate, personal emotions regarding family, responsibility, love, sacrifice, legacy, and sanity, both our own and that of a loved one, and the toll that has on us (it’s also about math, but I’ll get to that later). For me personally, though, the film- adapted from David Auburn’s stage play by Auburn and Rebecca Miller- is most importantly about the moment her father died for Catherine, and the aftershock of what that realization does to a person. Yes, her father physically died a week before we see Catherine (who wonders whether she’s inherited any of her father’s insanity), but one gets the impression he died for her emotionally a long time before that. When we do see that moment- it comes late in the film (which jumps from past to present seamlessly and effectively) at arguably Catherine’s greatest emotional high- we are witnesses to the greatest heartbreak any person could possibly feel, rendered with moving honesty and fearless feeling by director John Madden (“Shakespeare in Love”) and actors Gwyneth Paltrow and Anthony Hopkins. I identified with this film- for that reason and others, it is one of my favorite films of 2005.

In 2000, as many of you know, my grandfather passed away after five months with cancer. That summer my mother and I spent most of our time up in Ohio visiting him, taking care of things both around his house and in his room at the assisted living home he was at. In retrospect it was one of the most rewarding times I’ve had in my life and indisputably the toughest for me emotionally. In the roughly ten weeks I spent in Ohio that year, I saw my grandfather- one of the pillars of my youth and still a driving influence in my life- change from a warm, inviting individual to a mere shell of the person he once was, not because of anything that changed in him as a person, but because of a disease that debilitated him and made it impossible for him to function from day-to-day. It was a painful transformation to witness, and an experience that has informed who I am ever since in what I do, I would like to believe. Though still highly flawed, I would like to think that emotionally, I am a better person because of it.

Catherine’s situation in “Proof” is similar to my own. There are many differences- mine was a matter of months, hers years, and I didn’t have that moment of realization Catherine has (it was more of a slow realization of that probably being the last time I would ever see him)- but the emotional pain rings true, both when she is taking care of him and after he’s passed on. The reason she acts the way she does to her sister Claire (played by Hope Davis as a little to shrill and obvious, the film’s one misstep), who only appears to be thinking of Catherine’s well-being in suggesting she come with her to New York, is that she’s not only resentful of her sister’s seeming lack of care for their father, but also because after so long of going through what she has emotionally, she no longer feels as though she has to justify her actions and reactions to certain things to anybody. They should know what she’s gone through, and to be sensitive to her, regardless of how she treats them. But as I realized in the months and years since my own experiences back in 2000, you cannot- and should not- expect such a reaction from people who have not had to deal with such life-changing things so closely. To project your own frustration and pain that has had so long to gestate on others is a mistake, and there are more cathartic and healthy ways of letting go of it without shutting down emotionally. That Catherine- played by Paltrow as a woman closed off from everything outside of her own insular life, unable to let outsiders in after years of tough emotional battles; it’s her best performance in years- makes such mistakes makes her no less sympathetic (at least it shouldn’t when we consider what she’s dealt with); it just makes her human, and that she learns to deal with the difficulties life has thrown her, and begins to trust other people again (like Hal, the math student of her father’s played by a sympathetic and intelligent Jake Gyllenhaal (from “Donnie Darko”)) at the end, you see that she’ll come out from this experience a better person.

For many reviewers- all, in fact, that I’ve read- the movie is more about a revolutionary mathematical proof Hal finds in the father’s desk while rummaging through the hundreds of notebooks Robert filled with mindless scribbles over the past several years. The question as to who authored it- Catherine or her father- is the driving force behind the film’s final half. It’s an interesting mystery, but more interesting for me is the way Madden and his actors take Auburn’s play (by way of his and Miller’s screenplay) and transform it into a fascinating psychological study of grief and sanity and love and going on after devastating personal loss. For me, how people survive and find the strength to go on after experiencing events that test our emotions like that is the more fascinating mystery of “Proof,” and of life.