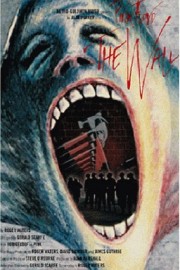

Pink Floyd The Wall

Author’s Note: While most of this review was written in August 2000 after a viewing of the film, I’ve added a few other thoughts I had after a recent viewing (as of 10/26/07) that I found interesting and worth mentioning. I hope you enjoy.

This evening I revisited Alan Parker’s film version of Pink Floyd’s rock opera “The Wall” for the first time in a few years, and yet again was drawn into its’ unique and provocative spell. In fact, this time it had an even more powerful effect on me, not only as an artist but as a music fan. My reaction as a movie buff could possibly be because I finally purchased a real version of the film (I previously saw it on VH1), and was able to watch it in its’ entirety (and believe me, when I got into DVD, this was going to be a surefire acquisition); however, something tells me that my reaction as an artist goes beyond that.

Ever since I became turned on to Pink Floyd’s epic music several years ago, they’ve remained a silent favorite in my collection. Everytime I listen to their music- be it the classic “Dark Side of the Moon” or the recent “Division Bell”- I’m always taken by the artistry and care the band takes to make the MUSIC (minus lyrics) as compelling and audacious as possible. Their lyrics- for the most part- exist simply to provide a more tangible form of musical imagery and storytelling when the music isn’t quite enough.

This is most evident in “The Wall,” a concept album created by Roger Waters musically visualizing the psychological breakdown of a rock artist (named Pink Floyd) burned out by the crowds, the drugs, the shows, and the inner turmoil that has infested his mind since childhood. For my money, it’s the best album they’ve done- based on what I’ve heard- and a true work of art. (For a more in-depth look at the origins of the story Waters tells, go to www.dvdverdict.com for a brilliant and fascinating examination of the film’s DVD release.)

In “The Wall” the film, the same themes of isolation and the supression of innermost feelings comes through as Pink (portrayed intensely and capably by musician Bob Geldof) sits in an L.A. hotel room watching an old WWII film (his father- we learn- was killed in WWII) and having vivid nightmares- or perhaps hallucinations- of his past and the feelings he keeps locked away…the most vivid of which is of him as a rock equivilant of Hitler- a fascist “God” preaching to his mindless, brainwashed disciples.

These are portrayed mostly through live-action sequences and fairly simple visual effects, though the most fantastic of these sequences are designed through the use of animation that could be seen as an introduction to American audiences to Japanese Anime. Both the live-action and animation sequences are strikingly realized by director Parker (“Evita,” “The Life of David Gale”) and animation designer Gerald Scarfe, working from the sparse screenplay by Waters (though really, the album is the script) in an effort that is- in this viewer’s mind- just as state-of-the-art than other live-action/animation combinations such as “Who Framed Roger Rabbit?” and- dare I say it- the likes of “Space Jam” and “Rocky and Bullwinkle.” This is the work of a true visionary…three in fact- Waters, Scarfe, and Parker. Many pigeonhole “Pink Floyd The Wall” as simply a 90 minute music video, but to do so is diminishing the impact of one of the most vital and extraordinary pieces of cinema ever created- even after 25 years since its’ original release. In other words, certainly one of the best films I’ve ever seen (and quite possibly a pinnacle in Parker’s career, I’d imagine).

In watching the film again recently, however, I was struck by something I’d never really considered before- what exactly is this movie trying to say, exactly? To be sure, there’s an anti-war theme that’s clear as day, as well as an indictment on the pressures and pratfalls of fame. But on the one hand, during the flashbacks of Pink as a child (which includes one of the film’s rare bits of humor in an in-joke where lyrics from Floyd’s hit “Money” are used as poetry Pink writes in class) in the “Another Brick in the Wall” sequences (among the film’s most iconic), the film condemns the type of harsh, robotic, too-well-organized school education that reigns in a free thinking society. On the other hand, however, Pink’s hallucinations of himself as a dictator indicate a perverse glee on the part of Pink, almost as if to endorse the idea of fascism. But such as the way with the greatest art, it is open to many interpretations, the one that makes the most sense in this case being that Waters and co. intended to show how Pink’s early education buried itself deep into his psyche, and as an explanation of his later view of himself as a sadistic dictator is infused by it. Still, the contradictory viewpoints do pose interesting questions to a viewer able to find behind the stylized visuals and powerhouse music.

The film isn’t completely off the hook, however. Even by dramatic film standards, the story (such as it is) has an all-too-somber mood most of the time, making humor a much desired commodity (though one could argue that there’s great dark humor in “The Trial” sequence, where Pink is on trial and all the people responsible for his state of mind are testifying against him). Still, if you can stand the slow, brooding tone of the film, it makes for compelling and surprisingly poignant cinema- a flawless realization of a landmark rock album. (Ironically, I have yet to mention the music explicitly, which is the central driving force of the film in that it tells the story (there’s little real dialogue in the film). Well, let me just say it’s great, and that you owe it to yourself to hear it if you haven’t already- either through watching the film or listening to the original album.)

Now I mentioned earlier that this viewing struck me deeper as an artist than it did the first time I saw it. Why is this perhaps? My belief is that probably great artist- I’m talking specifically about composers, songwriters, etc.- goes through this type of inner turmoil once in their life, and it can be triggered by one of several things. One possibility is that they are unable to create and express themselves through their art- be it because they are unable to come up with the ideas or because they are unable to find the time to put them down in some tangible form (or both). Another could be they suffer a tragic loss in their life, making them unable or uninspired to create (although in a lot of cases this can bring out the finest in an artist’s craft). Finally, there’s always the sheer inability to cope with the things and temptations that come with being an artist- in a rock artist’s case, the crowds, the drugs, the shows that could grow monotonous over time; I would be tempted to say that many of these factors led to Kurt Cobain’s suicide back in ’94. Have I gone through this? In a way, though not as severely as Floyd does in the film. Will I be able to bring myself back instead of submerging myself in my own psychological Hell as Floyd does? Well, it took a while, but I did indeed pull myself back, and I’m all the better for it. Besides, my career- as it stands now- is reasonably young still and (I hope) nowhere near reaching its’ full potential. My hope is that when it does, I might be capable of something as meaningful as what Waters and co. created here.