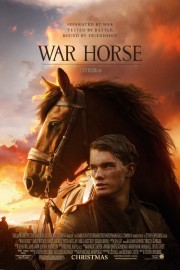

War Horse

“War Horse” is one of Steven Spielberg’s most emotional films. This isn’t to say it’s among the filmmaker’s best, but it does represent the director in complete command of his emotional instincts as a storyteller and an artist.

In reality, that’s the only way a film based on Michael Morpurgo’s children’s book could work on-screen. The story is, first and foremost, a director’s showcase as it tells the story of Joey, a horse who gets shipped off to the front lines when WWI breaks out, separating the colt from his owner, Albert (a very fine Jeremy Irvine). Albert has had Joey since he was a pup, when his drunken father (Peter Mullen) bought Joey at auction, risking the family farm. Unfortunately, it’s financial concerns that leads him to sell Joey for the war effort to a British officer (the superb Tom Hiddleston), leading Joey on a remarkable adventure as he meets all manner of people.

Because so much of the story follows Joey, and Joey lacks a voice of his own, Spielberg has quite a task in bringing “War Horse” to life. Rather than exaggerating Joey’s personality, or giving the horse an inner voice (similar to what Dreamworks animation did in one of their very best films, “Spirit: Stallion of the Cimarron”), Spielberg presents Joey as he is…a horse. That made it difficult to acclimate to the rhythms and pacing of storytelling Spielberg and his longtime editor, Michael Kahn, as Joey first finds himself at the front of a calvary charge before being taken by a couple of young German soldiers who go AWOL, which leads him to the care of you French girl (Celine Buckens) and her grandfather (a moving Niels Arestrup), only to find himself back in German hands pulling heavy artillery at the Battle of the Somme, one of the bloodiest battles in all of the Great War. Along the way, Joey is accompanied by Topthorn, a beautiful black steed that was part of the same calvary charge, and whose rider also died in battle.

In addition to the directorial challenges in bringing such a story to life, Spielberg and his screenwriters (Lee Hall and Richard Curtis) have to contend with the inevitable comparisons to the award-winning stage play, which used puppets to bring Joey to life on stage. But Spielberg is more than up to the task, as he brings the humanity he has displayed in films as varied as “E.T.,” “Saving Private Ryan,” and “The Color Purple” to bare in a film that dramatizes the idiocy of war not only by showing us the human toll, but also the effects it has on a horse like Joey. Indeed, some of the most heartbreaking scenes in the movie involve us seeing horses worked to death (literally) by armies with no real compassion for the animals; true, there are individuals on both sides who care for the animals, but the group think of the military leaders seems to be, “Well, better them than us.”

Oddly enough, the bond that I found myself most moved by in the movie was not that of Joey and Albert’s, although that is the central one (especially when Albert enlists, in hopes of finding Joey again), but Joey and Topthorn, the other horse at the center of the story. Anyone with pets of their own, I’m sure, will relate; after all, even if they can’t speak, anyone who has spent any amount of time around animals will tell you that animals that spend any amount of time around one another will connect, even if it is a tenuous one. That type of connection is central to “War Horse’s” impact on me, as Topthorn is injured, and Joey stands by his side, and even saves his life a couple of times. True, I’m sure a lot of this is dramatic license taken on the part of Morpurgo when he wrote his original novel, but for me, it became the heart of the story in the way Spielberg and his collaborators (most especially, composer John Williams, who writes some of his most emotional themes for the film) present it. “War Horse” isn’t a great film, but it is a greatly moving one, from a filmmaker who knows a story worth telling when he sees it, regardless of how challenging.