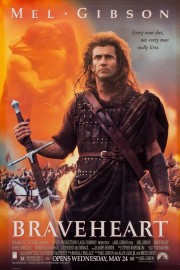

Braveheart

The years have not been kind for Mel Gibson’s epic film, his second as a director (behind 1993’s underappreciated “The Man Without a Face”). Not for the film itself, which is just as enthralling as it was when I first saw it a couple of weeks before its’ release in 1995. But while the film used to hold positions high on both my personal favorites and best films lists, it has dropped in the past decade off of my own list of 100 greatest films I’ve ever seen (it’s still just behind “Sherlock Jr.” and “The Crow” as one of my all-time favorites), not because the film has gotten worse, but because my cinematic landscape has grown.

So has the worlds. While “Braveheart” was inspired by epics past such as “Spartacus,” “Ran,” and “Lawrence of Arabia,” Gibson’s film itself led to- for better or worse- future epics like “The Lord of the Rings” trilogy, “Kingdom of Heaven,” “Gladiator,” “300,” and “Saving Private Ryan.” It also rates as the creative high point of Gibson’s career; his box-office bankability saw higher peaks before and after with “Lethal Weapon” sequels, “Ransom,” “What Women Want,” and “Signs,” but as an actor and a filmmaker, “Braveheart” is his undisputed high point. OK, the millions who were enthralled by his 2004 religious passion project “The Passion of the Christ” might argue with me on that, but “Braveheart” is his most complete vision. Critics bitched about the subplots that tilted the film’s running time towards three hours, but watching the film today- for the first time in many years- the subplots help paint a larger picture of the world Gibson creates onscreen around Scottish freedom fighter William Wallace. Even Spielberg’s WWII masterwork didn’t work on so broad a canvas.

Instead of just focusing in on his Wallace, a larger-than-life hero in the long-line of Gibson-played martyrs, Gibson and screenwriter Randall Wallace (no relation to William, and whom Gibson later collaborated with on “We Were Soldiers”) show us a country in turmoil in 13th Century Scotland. With no single heir to the thrown, Scotland is now at the hands of the ruthless English King Edward I (the late Patrick McGoohan), more popularly known in Scotland as “Longshanks.” Longshanks has learned the way to control the Scots is to appease their nobels through land and title, even as he maintains armies in England to keep the peace. Occasionally, an uprising will start, with some of the peasants taking matters into their own hands, but Longshanks is a ruthless one- onetime, he set up a meeting with some of the leaders of the clans to talk of peace, only to have them hanged.

The sight had a profound impact on young William Wallace, whose father and brother were supposed to be at the meeting. Now, however, they’re prepared to fight for their country’s freedom, leaving young William alone to man the farm. Their fight is lost though, and father and brother are among the casualties of the fight. After the funeral, William’s uncle Argyle (Brian Cox) takes the boy away to live with him, where he sees more of the world and learns several different languages.

Before being introduced to Wallace at an elder age (the one played by Gibson), Gibson fills more of the political landscape for us, including Longshanks arranging the marriage of his son Edward II (Peter Hanly) to Princess Isabelle of France (Sophie Marceau), although Edward seems more interested in friend Phillip than the lovely Princess, as well as a meeting in the Scottish city of Edinburgh between several of the nobels, including Robert the Bruce (Angus MacFadyen), whom many see as the rightful successor to the crown. Pointless plotting? Not in the least; Gibson’s setting the stage for the directions his story will go in the next 2 1/2 hours, when Gibson’s Wallace will be thrust into the spotlight of Scotland’s plight when he secretly marries childhood friend Murron (the lovely Catherine McCormack), who will later be murdered when British soldiers try to take sexual advantage of her. This is the moment that turns Wallace- who wanted to live in peace- into a man of action, and a hero whose stature will only grow to mythic proportions as he leads a rag-tag group of Scots (including Brendan Gleeson as best bud Hamish and David O’Hara as Stephen, an Irishman who’ll become a trusted ally in Wallace’s fight against the British and the politically-motivated noblemen) against Longshanks’ armies.

Gibson’s directorial eye doesn’t lose sight of the bigger picture; much as he did in “The Man Without a Face,” he pays close attention to the supporting characters that really make the film come to life. Has a cast not including Kevin Bacon (who starred in “Braveheart’s” main Oscar competition, Ron Howard’s “Apollo 13,” the same year) been so far-reaching in actors who either had already established themselves (McGoohan, Marceau, who was a big name in France at the time) or would go on to do so (Gleeson, O’Hara, McCormack, Cox) afterwards? In both “The Passion of the Christ” and “Apocalypto,” Gibson focused in on his protagonists while painting a picture of the worlds around them, but here he tells a far-reaching story with a central hero whose actions inspire those around him to act, and define their characters in that way. For critics, how was this a bad thing?

Of course, were “Braveheart” simply about the characters, it likely wouldn’t have had the lasting impact it’s had on modern epics. Where Gibson really raised the bar for those who followed was in his vivid action scenes. The graphic violence may have paved the way for “Ryan,” “Passion,” and “Rings,” but it’s in the way Gibson saw the strategies, shot the armies of hundreds of thousands (without the staggering level of CG we see today I might add) moving against each other, and technically achieved these sequences (his use of mechanical horses in particular during Stirling was a master stroke) that really left an impact on viewers. If there’s a viewer who wasn’t blown away by Mel’s impressive staging of the Battles of Stirling and Falkirk (where Oscar-winning cinematographer John Toll and nominated editor Stephen Rosenblum really strut their stuff, shooting and cutting the gritty and gruesome footage together brilliantly), and shocked by the brutality of it all, I haven’t met them. Those two sequences, perhaps more than any other, no doubt won Gibson the Best Director Oscar more than any others.

But the scene that always had the strongest impression on me takes place shortly after Murron’s death. The local Magistrate is looking to lure Wallace into a trap by desecrating the graves of his father and brother. Wallace rides into town like the Man With No Name, seemingly giving himself up. As the soldiers take the reins of his horse, however, Wallace and the people he’s inspired to his cause take action. Everything in this sequence is beautifully realized- the slow-motion camerawork, the crisp editing, the flawless execution, and James Horner’s visceral scoring- for maximum excitement and impact. The scene immediately after, where Wallace buries Murron’s body in a secret location, with her distraught and disapproving parents looking on, only adds to the sequence’s impact as the film’s critical tipping point. Not only is it great filmmaking, but it’s fantastic storytelling, allowing Gibson- an underrated actor whose rarely topped his work in this film- to also show us not just Wallace’s ferocity in battle but his tenderness that’ll maintain his humanity when faced with Longshanks’ uncompromising ruthlessness. True, Wallace’s affair with the French Princess later undercuts things a bit, and fudges facts for the sake of legend, but Murron’s influence of him is always seen as Wallace’s driving force.

Just as Murron is Wallace’s driving force, so- I believe- is James Horner’s score to this film. While the film wouldn’t work without Gibson’s conviction as both actor and director, I don’t think the film would be so memorable with Horner’s score, which has become overshadowed by his Oscar-winning work in “Titanic” in the 12 years since that film, but as Gibson said in his commentary for the film, Horner’s came first, and deserved the Oscar more (I mean come on, “Il Postino” Academy!!). If you want to know the piece of music that inspired me most on my current path, you’ll hear it in this film. Horner’s score inspired me so that my passion for film music became a vocation as a result of it. His hero’s theme is so exhilarating I heard it throughout my head trekking through Philmont Boy Scout camp that summer. His love theme so romantic it made me wish I had someone in my life to think of as I heard it. His action cues so riveting I couldn’t imagine anyone else topping them in excitement. That year, no one did. The same could be said for the movie itself, which feels more like a legendary hero’s adventure than vivid history, but I think you’ll agree, few filmmakers have been able to make such a combination of both before or since.