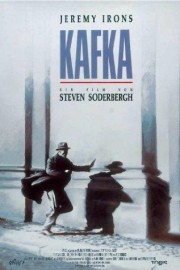

Kafka

As a second film, Steven Soderbergh’s “Kafka” was seen as the typical sophomore slump by many a critic, especially in the shadow of his Sundance (and Cannes) smash “sex, lies, and videotape.” True, it reeks of the sort of pretentious ambitions and details that would make any critic lose their lunch at the notion of reviewing it, but it’s also an intriguing and well-conceived thriller.

Working from a screenplay by Lem Dobbs (who would later write “Dark City” for Proyas and “The Limey,” again for Soderbergh), Soderbergh showed his experimental side early on in this film, building on the unorthodox storytelling of “sex, lies, and videotape,” and finding an ideal leading actor in Jeremy Irons. Not above taking risks himself, Irons plays Kafka, a file clerk at an insurance company who also fancies himself a writer (illusions are made to Franz Kafka’s real-life works, in both theme and in dialogue). One day, a dear friend of his- a one Edward Raban- goes missing from his office. His investigation of that disappearance leads him not only closer to a female co-worker (Theresa Russell, who plays Gabriela), but also further down a rabbit hole of conspiracy, political battles, and other paranoia-inducing dilemmas.

The choice of Prague to film in was a masterstroke, not only paying a tribute to Kafka himself (who was born in Prague), but also giving the film the old-World feel it requires, capturing the feel of the German Expressionism of Kafka’s time a la “The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari” and “Nosferatu.” Part of that is no doubt because of Soderbergh’s decision to shoot much of the film in black-and-white, which also allows cinematographer Walt Lloyd to evoke angles and shots from classics like “The Third Man,” also about one man’s journey into the true nature of how the world works.

That feel is also evoked in the remarkably conceived score by Cliff Martinez, who has continued to push the boundaries of experimental film writing for Soderbergh with his scores for “Solaris,” “Traffic,” and “King of the Hill.” But how I wish this score were available- of all of those, it’s perhaps the one I admire the most. So sad, so innovative in its’ suspenseful nature, and so powerful in how it drives the action.

For this film, Soderbergh gathered a cast of icons and character actors that has grown all the more impressive over the years. Past icons like Joel Grey, Ian Holm, and Sir Alec Guinness have particular personalities they bring to their respective characters- Grey a biting feel to his office manager, Holm a smart but untrustworthy nature to his mysterious Dr. Murneau, and Guinness that of a wise mentor to his chief clerk. Russell admittedly is an acting lightweight among superlative actors, but she still gives Gabriela an emotional center that makes the audience care about her well-being, and wonder about her motives. Character actors Jeroen Krabbe and Armin Mueller-Stahl were relative unknowns to most audiences at the time of the film’s release, but later success (Krabbe in Soderbergh’s criminally-underappreciated “King of the Hill” and “The Fugitive,” Mueller-Stahl as the father in “Shine” and a shady character in films from “The X-Files: Fight the Future” and “The International”) have only gone to enhance the foresight Soderbergh had to bring them in as a grave-digger and officer, respectively, who have insights and help for Kafka along the way.

But above all else, Irons delivers the film on his shoulders. While not shying away from his typically-stoic onscreen persona, Irons makes Kafka a sympathetic and tragic hero as circumstances lead him to a greater and sadder truth about the world than he would like to admit at the begin of the film. That truth is that the world is bigger than one person, and despite their best intentions, no one person can make a difference. A bleak message, but one in keeping with the real Kafka’s writings, as Welles showed so effortlessly in “The Trial.” Soderbergh has made better films in the intervening 18 years, but one can see the passionate experimentalist flair he’d display- and refine- in later films (“Solaris,” “Gray’s Anatomy,” and “Schizopolis”) front and center in this early effort.

A question- when are we gonna get to see this (and “King of the Hill”) on DVD? Of all of Soderbergh’s films, they’re the only two still not available on DVD. But maybe that’s a question for another review.