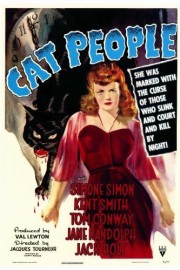

Cat People

Horror wasn’t always blood and guts and gratuitous nudity and things that pop out at you in the night. Well ok, it’s always been about the latter. Part of the pleasure of 1942’s “Cat People” is that it doesn’t make its demons pop out at you but rather grab hold of you, slowly, provocatively. No wonder it’s made such an impression on so many people over the years.

Back in the ’40s there was an economy of resources that made movies in those days, well, distinctive. Especially when it came to horror and thrillers. Sure, Hitchcock had Hollywood at his fingertips, but others had to improvise. The films produced by Val Lewton for RKO in the ’40s are the most lasting examples of such improvisation.

When he remade the film in the ’80s, writer-director Paul Schrader made the themes (and frights) of the original film explicit (and I mean really explicit). Personally, it was less effective as a result. But director Jacques Tourneur found just the right way to bring DeWitt Bodeen’s smart, insinuating screenplay to life. Namely, by taking it into the shadows of the world…and the mind.

The film stars Simone Simon as Irena, a young Serbian woman who catches the eye of Oliver Reed (Kent Smith), an architect, while she’s sketching a leopard in Central Park one day. He walks her home, they have tea, and not long after, they are married. But Irena is troubled. Her homeland has a folk legend about King John of Serbia, who drove the monsters out of the land. But some of the smartest, the leaders of such supernatural forces (who could take the form of cats), escaped. It is said their beliefs still hold true today.

Eventually, Oliver takes Irena to a friend who is a psychiatrist, who uses sinister psycho-babble to explain away her problems. When Irena learns that Oliver’s friend and co-worker Alice (Jane Randolph) knows about her issues, however, jealousy takes over Irena, and what began as a happy marriage turns into a triangle when Alice and Oliver begin to consider each other as “more than friends.” This leads to two of the film’s most enduring sequences (both among the best in all of horror cinema), the first when Alice is walking alone in the streets at night after an afternoon with Oliver and Irena. Irena understands now that Oliver and Alice are now becoming a couple. Alice feels a presence following her in the shadows. She quickens her pace. The second is when she gets to the hotel after a late-night work session/coffee with Oliver. She goes for a late-night swim, and still this presence follows her, which we know now is Irena. Tourneur’s use of shadow and sound effects are brilliant for what they imply. It’d be less effective otherwise. That’s why Shrader’s film didn’t work for me.

Upon first viewing, one might be inclined to consider Oliver’s treatment of Irena as insensitive, especially when it becomes clear that he and Alice’s feelings for one another are genuine. But the more one watches, and the more one has lived, the more it feels closer to the complexities of life. These are three people whose lives are eventually ruled by an extraordinary force none of them truly understand. One might be tempted to call it a curse, or fate, but regardless what you call it, there’s a fundamental sadness for all three that will never be easily shaken. Oliver’s caring for Irena never really wavers, and Alice just happens to be caught in the middle. But Irena is, in the end, doomed to tragedy. She cannot shake the deeply-held belief that her soul doesn’t belong to her, but to a force she cannot explain. Maybe in the end, she was able to find herself peace. Oliver’s final words- “Well, she never lied to us.”- make us feel like only through tragedy, he was able to understand his blushing bride completely.