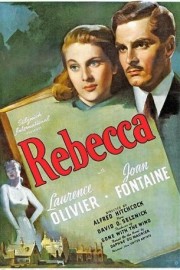

Rebecca

How curious that Alfred Hitchcock’s only film to win the Best Picture Oscar is one of his least-known among modern filmgoers? While most average moviewatchers can list off the definitive classics of “Vertigo,” “Psycho,” “North By Northwest,” “The Birds,” “Strangers on a Train,” and “Rear Window,” fewer people short of the most hard-core Hitchcock-philes know of “Rebecca,” his one collaboration with mega-producer David O. Selznick, and his first American production. And yet this film, adapted by the celebrated novel by Daphne du Maurier, appears now to be Hitchcock’s earliest dress-rehearsal for his most personal masterpiece, “Vertigo.” It’s not surprising really-both films are about women haunted by the specter of a dead woman, and men who are obsessed with the pain of the past.

The story is perfect for Hitchcock to weave his suspenseful artistry. Joan Fontaine stars as a young woman who is on vacation with her guardian Mrs. Van Hopper (a baudy and delightful Florence Bates) in Monte Carlo when she first lays eyes on Maxim de Winter (Sir Laurence Olivier), who appears to be attempting suicide. This first meeting sets the tone for their whole relationship to come. They begin to spend much time together. And as the woman and Mrs. Van Hopper are about to leave, she rushes to say goodbye to Mr. de Winter. Instead, he surprises her with a proposal of marriage, and an invitation to return to Manderley (his estate) with him. But the return to Manderley opens old wounds for Maxim, and for the young woman, the insecurities of being compared to a dead wife by all around her, especially the main housekeeper Mrs. Danvers (the sinister Judith Anderson), who was quite fond of the prior Mrs. de Winter, Rebecca.

If you ever had any thought of anyone other than the director as the true author of a film is, all one should do is look at the career of Alfred Hitchcock. No, he didn’t necessarily write the scripts (though he always seemed to be part of the process), but his fingerprints are all over each and every one of his greatest films (and even second-tier classics like “Rope,” “Dial M for Murder,” and “Suspicion,” the latter of which was immediately after “Rebecca” and won Joan Fontaine the Oscar many felt she deserved for the earlier film). He wasn’t necessarily one to use the same cast and crew save for a few instances (Cary Grant, Jimmy Stewart, composer Bernard Herrmann), but his films always carried his signature.

Compare “Rebecca” to “Vertigo.” Though the latter masterpiece is much darker than this film (and the work of a master in full bloom of his gifts), “Rebecca” is a truly macabre work, which no doubt appealed to the filmmaker for his first American production. The deeper our heroine (played by Fontaine in one of the most courageous of all film performances) digs into the secrets of Manderley, the more she sees the specter of Rebecca haunting over the place, much like Carlotta (the woman in the painting in “Vertigo”) haunts over Madeline, the young wife Jimmy Stewart’s Scottie is tailing. Rebecca’s memory lingers over all the people of Manderley, and Maxim most of all. Olivier’s Maxim is very much a prototype for Stewart’s Scottie, especially after Madeline (whom he has now fallen in love with) falls to her death. But Maxim has a deeper sense of guilt and loss over Rebecca’s death, which Fontaine’s new Mrs. de Winter senses, but is unsure of until one night when the boat Rebecca was lost at sea in was found, opening up old wounds and the thought that Rebecca’s death might be more than accidental. True, the stories move off into different directions, but the themes are strikingly similar when the new Mrs. de Winter (like Judy, the woman Scottie falls for after Madeline’s death) is caught between her new husband and the ghost of a woman from his past.

That Hitchcock’s mastery is so well-ingrained in each of his films, even at this turning point in his career (which had come after films like “The 39 Steps,” his original version of “The Man Who Knew Too Much,” and especially “The Lady Vanishes”), is remarkable. In a career that spanned 54 films and five decades, Hitchcock rarely had to deal with as strong as personality as he was behind the scenes, making his collaboration with the equally-iconoclastic Selznick a surprising one. Then again, they never worked together again. Thankfully, they saw fit to work together this once, and they made a powerful and poignant masterpiece.