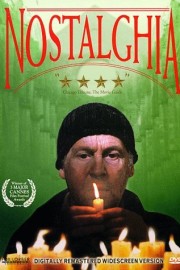

Nostalghia

The more one watches Andrei Tarkovsky’s work, the more one comes to an unmistakable conclusion: the Russian filmmaker never made a film that he didn’t appear to have some personal connection to, from his student film “The Steamroller and the Violin” to his 1986 farewell “The Sacrifice.” The only exception to that MIGHT be his 1972 adaptation of Stanislaw Lem’s “Solaris,” but even then you can’t help but think that the reasons he chose the story were likely due to an emotional connection to the ideas contained within.

“Nostalghia” was Tarkovsky’s sixth feature film, and you can see all of the filmmaker’s artistic qualities in full bloom: the long takes and tracking shots; the philosophical dialogue which defines situation and character; the blending of black-and-white photography and color; the reverence towards art; the reminiscing of the past, and the search for peace that all of his characters strive for. This was Tarkovsky’s first film in exile from Russia (he filmed it in Italy), and thankfully, all of the master’s artistry followed him out of Russia, where he had dealt with much in the way of censorship and political unrest that led to cutting of some of his greatest films (there have been at least three versions of his masterpiece “Andrei Rublev” screened over the years), and after the miserable experience making his sterile but poetic 1979 film “Stalker,” there was really nothing left for him as a filmmaker in the Soviet Union.

Thankfully, exile allowed Tarkovsky to deepen his creative palette further, and to tell stories that were unquestionably personal to him, and were uncompromised by censors. In “Nostalghia,” it’s the story of a Russian poet (Andrei Gorchakov, played by Oleg Yankovskiy) who travels the Italian countryside in search of information on an 18th Century Russian composer with a translator (the lovely Eugenia, played by Domiziana Giordano). On his journey, he comes in contact with an old man (Domenico, played by Bergman’s long-time star Erland Josephson, who would later star in Tarkovsky’s “The Sacrifice”) who once locked his family away for seven years. Everyone thinks him crazy for his actions, and wonders if he wants to commit suicide when he goes into the local pool with a lit candle. But Andrei is intrigued by the man, and the rest of the film is spent attempting to connect with Domenico, to understand the nature of his actions, and eventually to be inspired by them.

The thing one viewers must understand about Tarkovsky’s films before seeing any of them is that even at their best, they are capable of trying your patience. Tarkovsky’s work is built on subtle visual beauty enhanced by sound effects and music for a truly poetic cinematic experience. Dialogue is only of interest to the filmmaker if it has a philosophical purpose, or is able to allow us to understand his characters better. This is part of the appeal for me in watching his films: his approach to the medium is simple, but one would never call him a simple filmmaker. There’s a great deal of intellectual and emotional intrigue in what actions mean, what they say about the individual performing them.

Never is this more evident than in “Nostalghia’s” final passages, where the poet (inspired by Domenico’s example) lights a candle, goes into St. Catharine’s pool, and tries to walk across the bottom of the pool, all the while with the candle still lit. If it goes out, he goes back to the beginning, lights the candle again, and begins to walk again. The purpose of this act is never spelled out in the film; Tarkovsky leaves it to his audience to figure that out. Like all of Tarkovsky’s characters, however, the poet is driven by a spiritual and emotional journey that gets to the heart of what the idea of “faith” is: that our actions have meaning, not just for us but to the universe. Think of the young bellcaster in “Rublev,” whose audacity brought something so beautiful into the world it inspired the Russian icon painter to create again; the Stalker (whose fate is to lead others through the Zone without ever seeking out anything for his own gain) in “Stalker”; and the patriarch who, upon hearing the WWIII is imminent, asks for his family to be spare over himself in “The Sacrifice.”

The spiritual fulfillment of man is ultimately Tarkovsky’s only subject in all of his films. When our spirit is renewed we can accomplish more than we ever imagined; when our spirit is empty, when we lose the belief that our actions have no meaning, there’s nothing left for us but madness, and death. No other filmmaker has found so simple a way of expressing so complex an idea. Does the poet make it across the pool with the candle lit? Yes. What is accomplished by doing so? That’s for each of us to know for ourselves.