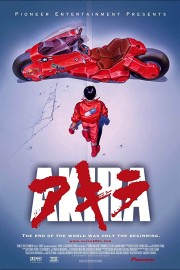

Akira

Katsuhiro Otomo’s adaptation of his own manga, “Akira,” remains one of the landmarks of modern animation, and one of the greatest of Japanese animation. Released in 1988, the film opened up American audiences to the idea of animated films not made for kids. Before its release, anime was merely a cult curiosity; after “Akira,” it was still more of a cult genre, but the cult was much bigger, and led the way to masterworks like “Ghost in the Shell,” “Perfect Blue,” and the films of Hayao Miyazaki finding audiences.

The film opens with a scene of 1988 Tokyo, and an atom bomb explosion occurring; WWIII has happened. Thirty years later, in 2019, the remnants of the old city are fallen to waste, and now neo-Tokyo is a futuristic landscape like so many ’80s cities: think “Blade Runner,” “Brazil,” and “Robocop.” One night, a biker gang led by Keneda and his best friend, Tetsuo, get into a fight with a rival gang, the Clowns, that spills into the streets. As the chase goes on, Tetsuo runs into a young boy who is being hunted by the authorities. The boy has a curiously odd look to him, and seems capable of telekinetic powers. When Tetsuo runs into the boy when their chases coincide, the authorities, and some mysterious characters take Tetsuo into custody.

It had been quite a while since I had last watched “Akira.” The film’s greatness as cinema has always been evident, but the story has always felt confusing, which shouldn’t be surprising– most anime plots border on the convoluted. This time, however, the film engrossed me completely is the universe Otomo created: the political unrest that mirrors what was going on in neighboring China at the time (parallels to the Tiananmen Square protests of the time exist in several scenes); the secrecy of the military in experimenting with science; the religious fervor of a cult that awaits the return of Akira, a mysterious entity who they think will deliver them; and, of course, the unique and bizarre science at work in this fantasy world. But more than anything else, what stands out most in the story now is the friendship between Kaneda, who is worried for his life-long friend, and Tetsuo, whose powers are uncontrollable to the point of bringing forth another Armageddon. Depth of feeling is not really a strong suit of anime, save for the work of Miyazaki, but the film’s epic finale wouldn’t work were we not engaged in the personal battle between these two friends. Kaneda has always been the strong one, always stepping in to fight Tetsuo’s battles; now it is Tetsuo who is the stronger of the two– resentful of his station as Kaneda’s sidekick, Tetsuo’s rage fuels his use of his powers, making the stakes in the final half an hour emotional as well as visceral.

But while the story makes “Akira” a great film, it’s the style that makes it a legendary work of art in not just animation but any sort of filmmaking. Otomo was a comic book artist and writer before he made his filmmaking debut with “Akira,” and I’m not sure if many would argue if I likened his accomplishment to being the “Citizen Kane” of animation. His use of color and his gift for pacing creates a truly kinetic visual experience for 125 minutes, especially when the truly fantastic occurs, like the three children whose use of their own powers make for some truly unsettling images (like the giant toy bear and rabbit they make in a seemingly hallucinating Tetsuo’s hospital room), or when the biological entities that make up the idea of “Akira” become one with Tetsuo, creating a monster of genuine terror. Equally important, however, is a musical score by Geinoh Yamashirogumi that is as spiritual at times as it is exciting at others. Be it the percussive drive of the action cues to the almost haunting emotion that is heard during the film’s enigmatic conclusion, the music of “Akira” is nearly as groundbreaking and beautiful as the film itself. When Otomo returned to large-scale epic anime with “Steamboy,” it was impossible not to be a bit disappointed with the results (although I still enjoyed it), but that’s what happens when your first film makes the impact “Akira” had not just on the particular medium it was made in, but on filmmaking as a whole.