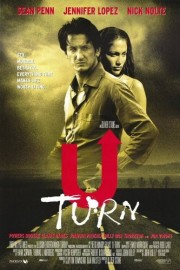

U-Turn

Oliver Stone takes a break from social and political concerns with “U-Turn,” which is less a film noir than a pure grindhouse film. Yes, we have femme fatales; a drifter that gets caught up in crime; and the jealous husband that seems natural for this type of film. But this film has less in common with modern noir classics like “Red Rock West,” “The Last Seduction,” and “L.A. Confidential” than it does with Quentin Tarantino’s “Kill Bill” and “Death Proof” (from “Grindhouse”), and last year’s “Machete.” There’s not an ounce of morality in any of these characters, and the film is more enjoyable for it.

Sean Penn plays Bobby, a drifter on the road to Vegas to settle some past debts when his car breaks down. He’s able to drive it into the town of Superior, Arizona and to a garage on the outskirts of town run by a hillbilly mechanic (Billy Bob Thornton in a wickedly funny performance). He leaves the car, and goes into town, where he gets caught up with all manner of character: namely, a young wife (Jennifer Lopez) and her grizzled husband (Nick Nolte), both of whom try to convince Bobby to kill the other. Bobby is intrigued, but it’s not long before he realizes he needs to get the Hell out of dodge ASAP.

More so than writer John Ridley’s surreal and pitch-black screenplay, based on his own novel, Stray Dogs, the two collaborators that are Stone’s biggest assets in making “U-Turn” are cinematographer Robert Richardson and composer Ennio Morricone. Gone are the stylized technical challenges Richardson and Stone perfected in “JFK” and “Nixon”; now, Richardson and Stone are playing down-and-dirty with style to capture the ’70s grindhouse aesthetic Stone grew up watching, or at least, wanted to watch while growing up. (When asked why he made the film, Stone said that he wanted to make a film “he would have liked to have seen as a teenager.”) The camerawork matches the material– both are intended to make you feel all dirty inside.

Complimenting the story, beat for darkly funny beat, is Ennio Morricone’s score. The soundtrack has a lot of great, classic songs (especially ironic is Johnny Cash’s “Ring of Fire,” considering co-star Joaquin Phoenix would play Cash eight years later in “Walk the Line”), but it’s Morricone’s distinctly surreal music that keeps you glued to the screen as the story goes between the good, the bad, and the just plain bizarre as Bobby runs into all manner of character in Superior, from a diner waitress named Flo (Julie Hagerty); Claire Danes’s flirty Lolita and her psycho boyfriend, played by Phoenix; the town sheriff (Powers Booth); as well as a local wiseman (the superb Jon Voight), a blind half-Indian who turns out to be the only individual in town without an agenda, and actually gives Bobby some good advice about not being so certain as to what he’s getting into.

By the end, Stone has put his characters, and us, through all manners of twists and turns. The title is fitting: once the film goes down one path, there’s no turning back. It all feels like some kind of sick joke once the vultures start swooping down (literally) by the end of the film, and really, that seems to be the point, and it’s a credit to the director that his cast (led by great work by Penn, Lopez, and a truly nasty Nolte) are ready to go wherever he decides to lead them. Watching the film for the first time since 1997, I’m glad I decided to follow Stone down this perverse rabbit hole as well.