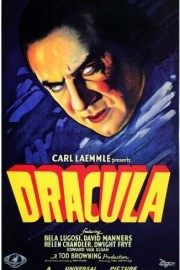

Dracula

Even though it is the first, significant adaptation of Bram Stoker’s iconic novel, Dracula, of the sound era (which was barely four years old at the time), Tod Browning’s film feels like a pivot in film horror– still grounded in the old ways of the silent film, but also implicitly aware of what sound can bring to the genre.

Or should I say, a lack of sound. Although the film can be experienced with a score composed recently by Philip Glass, and performed by Kronos Quartet, I very much urge viewers to watch it for the first time with the original, 1931 sound track, which– save for some brief excerpts from “Swan Lake” –is silent, except for the dialogue and sound effects. Thankfully, with DVD and Blu-Ray, we’re able to have that choice. This was the first time I’ve watched “Dracula” with the original sound track, and the experience is truly haunting, and unforgettable: the lack of an original score adds much to the terror, and the eerie tale being told.

And then, we have Bela Lugosi’s Count. Arguably more famous now for his collaborations with B-grade director Edward D. Wood Jr., watching Lugosi’s Dracula for the first time in years (and after the films he made with Wood), and we see the alluring qualities that made Lugosi so intriguing to the hapless filmmaker in the first place: those hypnotic eyes; that odd, fascinating way of delivering dialogue (has the phrase, “I never drink…wine.”, ever been uttered so chillingly?); and the seductive menace of his way of moving. He inhabits the role in a way no other actor ever has, while also setting the template for every actor who would play the role afterwards, who copied the theatricality (Christopher Lee, Gary Oldman), but not the dark soul that Lugosi brought to the character. Max Schrek’s Count Orlok in the greatest vampire film, Murnau’s silent “Nosferatu,” is more chilling, but Lugosi’s is more influential; indeed, given how many times we’ve seen Dracula on-screen, or just been treated to the idea of vampirism in general over the years in everything from “Twilight” to “Buffy the Vampire Slayer” to even a film like “Van Helsing,” this film is a benchmark for how one can portray the seductive evil at the heart of Stoker’s story. I haven’t really touched on that story in this review, but only because anyone with any familiarity with horror, or film, probably knows the story beats anyway. The important things here are the qualities that, to me, differentiate the film from its successors in bringing the story to life.

And yet there’s so much I haven’t talked about: the performances, which are theatrical in physical mannerisms in the same way the old silent films required. The film’s look, which– like Universal’s other iconic monster film from 1931, “Frankenstein” –borrowed much from German Expressionism, and indeed, Browning’s cinematographer on this film (Karl Freund) was a veteran of Murnau’s silent classics. And then there’s Browning himself, who is one of the most important directors in horror history between this film, his collaborations with other important horror icons like Lon Cheney Sr., and “Freaks,” his 1932 masterpiece that remains one of the most original and surreal films, of any genre, ever made. But that’s for another time. This review is about basking in the terrifying pleasures of Browning’s essential film about one of the great movie monsters of all-time.