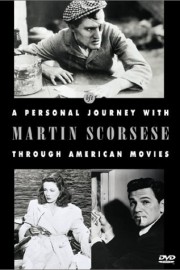

A Personal Journey With Martin Scorsese Through American Movies

Of all of the directors that came out of the “Film Generation” that began making films in the 1970s, it’s perhaps inevitable that Martin Scorsese is the most beloved among film fans. Although his films are a large part of that, it’s also the unabashed love for cinema and its legacy that plays a large part in that. Whether you’re hearing one of his commentaries, or reading an article or interview with him, the passion comes through his words, and get you right to the heart of this master by putting you in touch with the asthmatic New York boy who spent his days alone, in darkened movie theatres, with people who put dreams up on-screen and 24 frames per second.

In 1995, Scorsese made a four-hour documentary for the British Film Institute in which he sat in a chair, and looking straight into the camera, tells the viewer about the origins of his love for cinema, and about the films, and filmmakers, that have inspired him the most. Watching it is like listening to Scorsese, who was raised in the old-school Catholic tradition before Vatican II in the 1960s, sit in a confessional, telling a priest his sins. It’s a must-see for anyone who claims to care about movies at all.

Rather than just go through a film-by-film analysis akin to just rattling off his favorite films of all-time, Scorsese and his co-writer/co-director, Michael Henry Wilson, structure the film into five sections, spread out over three parts: “The Director’s Dilemma,” in which Scorsese examines the difficult balancing act between financial success and personal expression in filmmaking; “The Director as Storyteller,” in which Scorsese studies how directors sometimes move between genres like the Western, the Gangster Film, and the Musical– and sometimes within them –to explore different themes and ways of telling a story; “The Director as Illusionist,” where Scorsese explores the technical evolution of filmmaking over the years; “The Director as Smuggler,” in which Marty looks at the many types of films, from the early film noirs and B-movies of the ’40s and ’50s to major studio projects, and how filmmakers have brought subversive and controversial material into the cinema by hiding it in plain sight; and finally, “The Director as Iconoclast,” where Scorsese looks at some of the boldest, and most blatantly controversial, filmmakers, and how they managed to flourish, or were swatted down by the “powers that be.”

Among the most remarkable of Scorsese’s accomplishments with this film is how fluidly he sometimes moves from section-to-section using certain films, and certain filmmakers, as pivot points. One such example is the 1942 film, “Cat People.” Scorsese introduces the film at the very end of the “Illusionist” section, with its use of shadow and low-budget tactics to create a frightening atmosphere, and continues to delve into the film in terms of its themes when he starts the section devoted to “Smugglers.” His stamp of approval for the film is likely part of what led to the recent rediscovery of “People” and the other films of producer Val Lewton from the ’40s that Scorsese illuminates in this documentary; for the re-release of Warner Bros.’s fantastic Lewton box set, Scorsese even does a feature-length documentary about Lewton’s films that is, like this film, required viewing for film geeks.

One of the other pivotal figures, and films, in Scorsese’s documentary is the director, Vincente Minnelli, and his beloved 1952 film, “The Bad and the Beautiful.” Minnelli comes up a lot in “A Personal Journey,” whether it’s his duel Hollywood satires “Bad and the Beautiful” and ” Two Weeks in Another Town,” his classic musicals, “Meet Me in St. Louis” and “The Band Wagon,” or his thriller, “Some Came Running,” which Scorsese presents as a great example of how filmmakers used the Cinemascope widescreen format that was introduced in the ’50s. His adoration for both Minnelli and Lewton’s work points up one of the great values of Scorsese’s documentary, which is that, with Marty, is isn’t just the great, iconic directors like Kubrick, John Ford, Elia Kazan, Billy Wilder, or Orson Welles that fueled his passion for film. For him, lesser-remembered directors such as Minnelli, Budd Boetticher (“The Tall T”), Anthony Mann (“T-Men”), and Andre DeToth (“Crime Wave”) also had a profound impact on Scorsese as his life led him from the streets of New York to one of the most extraordinary careers in film history. Four hours of film studies through the eyes of this master flies by like the events in one day in the life of Henry Hill at the end of Scorsese’s “GoodFellas,” except Marty’s drug is the exhilarating high one can only get from the most creative and lively filmmakers bring their visions to life. Ever since I first saw this film in 2001, I’ve been priviledged to have Marty as one of my most trusted dealers.