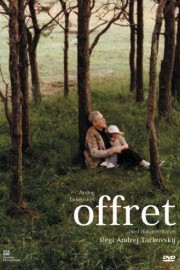

The Sacrifice

Everything that Andrei Tarkovsky knows about filmmaking is brought to full fruition in his final film, “The Sacrifice.” Long exiled from his home country, Tarkovsky came to Sweden, and the island of Faro– where another legendary filmmaker, Ingmar Bergman, lived and worked with absolute freedom –and made a film that is not only a culmination of Tarkovsky’s work, but an extension of Bergman’s. It’s not surprising, as Bergman himself said, after watching Tarkovsky’s first feature, “Suddenly I found myself standing at the door of a room, the keys to which, until then, had never been given to me. It was a room I had always wanted to enter and where he was moving freely and fully at ease.” The respect the two had for one another was evident in every film the other made from 1962 on, and especially in this one, where Bergman not only gave Tarkovsky access to locations, and, through the Swedish Film Institute, financing, but also use of two of his greatest collaborators: his cinematographer, Sven Nykvist, and the actor, Erland Josephson.

As he was making “The Sacrifice,” Tarkovsky was aware of his own mortality. He knew he was close to his own death, which came in December of 1986, shortly after the release of this film, of a brain tumor. The tragic irony of this is that it was the conditions on the set of an earlier film, 1979’s “Stalker” (the last he filmed in Russia) that led to Tarkovsky’s illness, and death. Tarkovsky literally gave his life for his art, which adds an even more profound dimension to his later films (“Stalker,” “Nostalghia,” “The Sacrifice,” the last two of which were made in exile) than they already possess.

In “The Sacrifice,” Josephson (who also appeared in “Nostalghia”) stars as Alexander, a father and husband who is first seen planting a tree with his young son, who does not speak. It is Alexander’s birthday, and friends and family come to celebrate bearing gifts. The most intriguing of these people is Otto (Allan Edwall), the postman on the island, who is, first and foremost, a student of philosophy, and a “collector of incidents”; he tells a story of a woman who had a picture taken with her son before he goes off to fight in WWII. She forgot to pick up the picture, which was her last with him; he died shortly after being drafted. Twenty years after the last picture, she has moved on, and decides to get a photograph taken of herself. But, when she gets the prints back, she is not alone…her son is in the picture as well, in the same clothes he was in when they took the picture twenty years ago. In many ways, this story is comparable to the act of filmmaking itself, wherein every film is a picture taken that reflects the life, and philosophy, of the filmmaker themselves when at the time they made the film. (Well, that’s true of the greatest ones, at least.) Later in the day, jets are heard overhead, and an announcement comes on the television that the world is on the brink of WWIII. Rather than asking for salvation for himself, however, Alexander prays that his family is spared, offering himself as a sacrifice.

Having seen all of his films, I know from first-hand experience how difficult it is to grow accustomed Tarkovsky’s deliberate, patient style. The long takes; the longer silences; the sparse use of music, and not in the way we’re used to in films; the ponderous, almost indulgently so, dialogue about philosophical and spiritual subjects. It’s not always easy to sit through even the director’s greatest films. As he got closer to death, his style became less accessible, and his stories less linear in the way they were told. And yet, it is this precise style that first drew me in to Tarkovsky’s cinema when I saw “Stalker” in 1997. Even fans of some of his films find that one challenging, but like a student who finds inspiration in one of his professor’s ideas of the world, I was immediately drawn in, and by the time I had watched all seven of Tarkovsky’s features (culminating, I believe, with “The Sacrifice” ten years ago), my way of looking at cinema had changed forever.

One of the most difficult aspects of Tarkovsky’s work is his use of, what he called, “poetic linkages.” These are sequence that don’t necessarily have a direct connection to the story, but act as an emotional reflection of the narrative. In “The Sacrifice,” it was particularly difficult to see how these connections worked the first time I watched it, but as I’ve written more about Tarkovsky (and read his own book, Sculpting in Time), I found the film much more accessible. A scene that happens in the second half of the film, where Alexander goes to the house of one of his maids, and asks for salvation for his family, and ends up making love to her, feels less like an actual occurrence in the story now, and more like a dream of Alexander’s after he’s laid down, despairing about the tragedy that might come. Since we’ve seen the postman make the recommendation to Alexander that he do this very thing (go to the maid, and lay down with her), we assume, at first, that he actually does sneak away and do so. However, the visual look of the sequence is not as “clean” as the rest of the film; plus, how do we explain seeing him wake up in his own house after seeing them start to make love?

In the last 30 minutes of the film, Tarkovsky stages one of his most visually elegant, yet most spiritually complex, sequences. After waking up, Alexander sneaks around inside, and outside, his house, as his family speaks of Alexander’s desire to go to Australia. He puts on a Japanese robe he owns (we learn he believes that he and his son were Japanese in an earlier life), plays some ancient Japanese music as he sets his house ablaze. He exits the house, and we see him move away from the house as it burns to the ground. Why? Has he lost all hope for living now that the stage is set for death? Is THIS his sacrifice– the ending of HIS life, as he knows it, for the lives of his family? A case can be made for either possibility. One thing, however, is undeniable: with his last film, in his last months, Andrei Tarkovsky was still searching for the answers to life’s “big” questions. I’d like to think he discovered those answers for himself with his death, but I do know this– with his films, he’s inspired my own search for answers in life. Few other filmmakers have done more for my own spiritual quest.