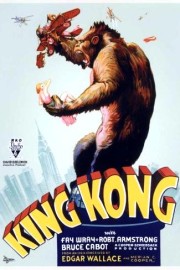

King Kong (’33)

If it did nothing else, Peter Jackson’s passionate, epic remake of “King Kong” assured us, sooner rather than later, of getting the 1933 masterpiece on DVD. Of course, the movie was coming anyway, but there seemed to be an urgency to do so when, after he completed the “Lord of the Rings” trilogy, he was offered a small fortune to finally bring his remake to life.

I discussed Jackson’s film plenty in 2005, though; now, it’s finally time to go back, and talk about the original, 1933 adventure from Merian C. Cooper and Ernest Scheodsack. The techniques they employed are quaint by today’s standards, but the scope of the film remains just as potent as modern standard bearers like “Jurassic Park,” “The Lord of the Rings,” and the “Harry Potter” films.

What strikes me in watching “King Kong” for the first time since 2005, however, is how fast-paced it is. Unlike today’s epics, which typically fall on the long side of two hours, “Kong” is a brisk 100 minutes (about 80 minutes shorter than Jackson’s film). And yet, it doesn’t feel like the movie sacrifices anything in terms of character and story, even after Ann Darrow (Fay Wray’s out-of-work actress) is taken by Kong at the 45 minute mark. The screenplay by James Ashmore Creelman and Ruth Rose, based on ideas by Cooper and Edgar Wallace, is a model of economic, and cinematic, storytelling, and a great example of how little most writers have learned from the classic films when it comes to writing modern adventures. Now, it’s almost always about the effects, leaving the human characters out to dry. Granted, only three characters in “Kong” get serviced in terms of being fleshed out– Darrow, filmmaker Carl Denham (Robert Armstrong), and the first mate (Bruce Cabot) who falls in love with Darrow –but that’s more than enough for this film.

Of course, I almost forgot that there’s one other character that is well-developed, and that’s Kong himself. It’s easy to watch the film, and marvel at the stop-motion animation by Willis O’Brien and his team, which lacks the reality of today’s visual effects, but makes up for it in the mood and effect of their unreality, which is just as powerful. However, it’s the way O’Brien and the filmmakers develop Kong as a character, less a monster like the dinosaurs we see on Skull Island, and more a misunderstood outsider, who wants to protect Ann Darrow from the dangers around her, and comes to care about her. The parallels with “Beauty and the Beast” are unmistakable, even if they aren’t quite as played out as they are in Jackson’s film. In its own way, Kong is the predecessor of characters such as Gollum, Caesar (the ape leader from “Rise of the Planet of the Apes”), Snowy (the dog from “The Adventures of Tintin”), Dobby (the house elf from “Harry Potter”), the Hulk, and any other character where technology– and sometimes, a human performer, in today’s performance-capture landscape –has been asked to bring a main character to life. But Kong remains at the pinnacle of that list, not because of how life-like the effects are, but because of the emotion and imagination O’Brien, Cooper, and Scheodsack brought to their creation, which still has the power to amaze 80 years later.