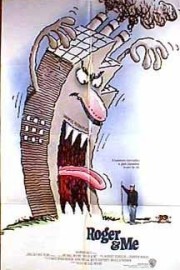

Roger & Me

Before he became a political firebrand during the George W. Bush era with “Bowling for Columbine” and “Fahrenheit 9/11,” Michael Moore was a populist commentator on the slow, painful death of the American Dream. In 2007, he began getting back to those roots with “SiCKO,” and again in 2009 with “Capitalism: A Love Story,” and even though he hasn’t made a film since “Capitalism,” instead focusing his activism for the working class on Twitter and other social networks, I hope he gets back to that some day.

Of his films, none of them have the sadness, and pathos, of his debut movie, “Roger & Me.” In it, Moore has a front-row seat to the decimation of his hometown in Flint, Michigan, after the GM car plant in town is shut down as corporations, in the ’80s, began outsourcing jobs to make more money. All the while, Moore goes on a hunt for GM CEO Roger Smith, in hopes of getting him to come to Flint, and maybe reconsider after seeing what’s happened to his hometown. If you’re familiar with Moore’s films over the years, however, you know the outcome.

With his documentaries, Moore changed the medium in a way that we’re still seeing to this day. Rather than simply observing life, Moore brought an element of investigative journalism that went beyond observation, and into demanding action. Of course, the personal nature of the film– that his subjects are people he’s known since childhood –required a less objective approach. It’s one that’s gotten him more than his fair share of critics over the years (not undeservingly, to be honest), mainly because it thrusts him at the center of his subject, leaving him open to criticism for grandstanding. However, as front-and-center as Moore is during his movies (often appearing on-screen while interviewing people), his subjects always come first; his personal approach to his style of filmmaking makes us more emotionally invested in the stories he’s telling.

That’s a key part of “Roger & Me’s” success as filmmaking. We see Moore interview celebrities such as Pat Boone (a hometown hero who was a spokesman for GM at one time); Anita Bryant; Bob Eubanks (the host of “The Newlywed Game”); and Miss Michigan, who would go on to become Miss America after she was interviewed by Moore. Their sheltered views on what’s going on in Flint speaks volumes to the disconnect the privileged often have with the everyman; now, it sounds exactly like talking points we’ve heard constantly as we’ve experienced the Great Recession that hit in 2008. But for the people of Flint, it’s been nothing but Depression since the late ’80s, and the fact that Moore continues to illuminate the city’s plight shows that, for as successful as Moore has gotten, he’s still a blue-collar individual at heart, and he always will be. And if he gets back to making movies sometime soon, hopefully, he’ll remain just as grounded, and just as pointed in his desire to put working-class needs above political motivations. In his best films (none better than “Roger & Me”), that’s where his greatest, most subversive talents come alive, and I wouldn’t have it any other way.