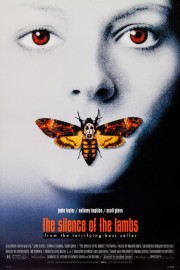

The Silence of the Lambs

The greatest compliment I can extend Jodie Foster as an actress is that it’s hard to see her playing a truly, helpless woman. Yes, she was a woman who was raped in “Accused,” but the strength she conveys throughout the rest of that movie was nothing short of remarkable, more than worthy of her Best Actress Oscar, a win she would duplicated less than five years later for “The Silence of the Lambs.” That performance would set the tone for her work since, in a way, with her work in films ranging from “The Brave One” (profoundly underrated), “Contact,” “Panic Room,” “Inside Man,” “Elysium,” and “Flight Plan” trading on her steely resolve that can hide a painful vulnerability, regardless of the overall film’s quality.

As Clarice Starling, a training FBI agent and psychological profiler who is brought onto a high-profile case by her boss, Jack Crawford (Scott Glenn), Foster is the perfect foil for Dr. Hannibal Lecter, a vicious serial killer with a penchant for cannibalism, and played by Anthony Hopkins (who won Best Actor for the role) in one of the most iconic performances in movie history. It takes a special actress to be able to stand toe-to-toe with Hopkins, and Foster is more than up for the challenge. Our eyes stay focused on the sight of Clarice and Lecter, during their meetings, involved in a psychological duel as Starling begins to see, for the first time in her life, real evil. Crawford warns her against telling Lecter any personal information, but when she tries to push him for information that might help in the capture of Buffalo Bill (Ted Levine), who’s been skinning young women, and killing them, Lecter plays hard ball, and Clarice relents. What transpires between them is a meeting of minds, and souls, that has a profound effect on both of them, which was later explored, to lesser effect, in “Hannibal,” both the Thomas Harris novel (which was polarizing, to say the least), and Ridley Scott’s 2001 film, which put Julianne Moore in the role of Clarice after Foster passed. But what Clarice and Lecter share is a connection of the mind, not the heart, and even though Lecter appears to have sympathy for Clarice, it’s a means to an end for him, just as sharing this personal information is for her. But while Lecter is a sociopath, incapable of real emotion, what Lecter forces her to reveal makes Clarice all-too-vulnerable, and it makes us all the more concerned for Starling when she finds herself in Buffalo Bill’s house. Thankfully, Bill isn’t quite as precise or calculating as Lecter, giving Clarice the upper hand when it comes to capturing him, and saving the life of a senator’s daughter.

The precision of thought with which Lecter conducts himself, both with Clarice and others, is matched by Jonathan Demme’s direction of the film, and of Ted Tally’s impeccable script from Harris’s novel. Demme’s always been a tough one to get a grasp on as a director for me. On the one hand, I love “Lambs,” “Philadelphia,” and really admired the personal touch of his 2008 film, “Rachel Getting Married,” while at the same time, finding myself profoundly bothered by his 1998 film, “Beloved,” and a couple of remakes from the past decade, “The Truth About Charlie” (a reworking of the Stanley Donan classic, “Charade”) and “The Manchurian Candidate.” At some point, I’m definitely going to get into his pre-“Lambs” work, and hopefully, that will shed new light on him for me as a filmmaker, but just on the basis of the past 20 years, it’s hard to see his Oscar win for “Lambs” as anything but a fluke, regardless of the genius he shows in the film. His visual style for “Lambs,” worked out with cinematographer Tak Fujimoto, is a simple, but effective, series of close-ups and classical framing that ratchets up the tension during some sequences (the chase through Bill’s house, Lecter’s escape), and the emotional intensity of others, such as when Clarice is telling Lecter about what drove her to run away from her cousin’s farm after the death of her father; similarly, the musical score by Howard Shore is almost deceptively old-school in the way it helps tell the story emotionally, focusing less on iconic themes, and more on creating a sense of anxiety in the viewer. More importantly, though, Demme and Fujimoto focus on telling the story in as simple a manner as possible, without the flourishes or flash that marks all too many thrillers nowadays. Rather than turn Harris’s tale into a slasher movie, Demme makes Clarice the focal point, moving the “scene-stealers” like Lecter and Bill to the edges of the story without diminishing their importance to, what is really, Clarice’s journey. In a way, Joss Whedon copied this approach when he brought “Buffy the Vampire Slayer” to TV, and it comes to full fruition in a lot of the more devastating storylines of that show, when Buffy is made vulnerable, and needs to find the strength, and resolve, to persist. Like Clarice, she’s not looking for congratulations for a job well done when she saves the day; she’s looking to do something positive, that might make this world a better place, and silence the pain she’s lived with for so long.

It almost feels criminal to focus solely on the work of three people (including Hopkins) when it comes to a film where everyone brings their A-game, and there’s so much that stands out about the film. As Bill, Ted Levine goes all-in on a grotesque, and troubled, portrayal of a monster. As Dr. Chilton, the leading psychologist at the hospital where Lecter is kept, Anthony Heald is a sniveling, opportunistic weasel for whom we feel no sympathy when Lecter tells Clarice in the last scene he’s going to have “an old friend for dinner.” And there’s plenty of other plaudits to go around for actors like Glenn (as Crawford), Kasi Lemmons as Clarice’s friend at the academy, and Brooke Smith as Catherin Martin, the senator’s daughter who, herself, is less of a push-over than Bill expects, not to mention editor Craig McKay and production designer Kristi Zea, whose contributions to the film cannot be overstated. In the end, however, it’s fitting that everything seems to come back to Demme, Foster, and Hopkins, though, because that’s what it boiled down to during the film’s great box-office run; it’s Oscar night, when it became just the third film to win each of the “big five” Oscars (for Picture, Director, Actor, Actress, and Screenplay); and pretty much any discussion of the film since. And you know what? They deserve it to be the case, because without their inspired collaboration, “The Silence of the Lambs” would just be another police procedural, and worse, Hannibal Lecter would be just another horror movie serial killer that is interchangeable with all the rest.