Full Metal Jacket

Whereas Stanley Kubrick had become known as being ahead of his time with his films (best exemplified by “2001,” “Dr. Strangelove,” “Lolita,” and “A Clockwork Orange”), “Full Metal Jacket” seemed to be just behind the times. Although other filmmakers had looked at the horror that was the Vietnam War years before (especially “Apocalypse Now”), the release in 1986 of Oliver Stone’s “Platoon,” based on the director’s own experiences, made “Jacket” feel irrelevant to many people. The fact that Kubrick shot the film in London, where he had been making his films since “Lolita,” didn’t help matters much once the film transitioned to the war zone. The notion of Kubrick making an irrelevant film by this point in his career is laughable, though, and watching the film, we see that Kubrick had bigger fish to fry that went beyond realism.

That’s established right at the top, as the first thing we see is recruits getting their heads shaved. A sea of shaved hair is the last thing we see before we go inside the barracks, and follow around Gunnery Sergeant Hartman as he roams around the room, shouting at these new recruits he lovingly calls “pukes.” Hartman is played by R. Lee Erney, who was a drill instructor during the war, and was so impressive to Kubrick with his authenticity that the exacting director allowed Erney to ad lib much of his dialogue. Erney sets the tone for this part of the movie, and it’s a powerful look at basic training that makes no one envious of the prospect of joining. It also shows Kubrick in his element as a chronicler of the dehumanization of man. Though the recruits are given nicknames that help define their personalities, throughout the process of training, they lose that personality, and become monotonous instruments of war. This is best represented in the character of Private Leonard “Gomer Pyle” Lawrence, a fat, clumsy recruit who draws the ire of Hartman, and scorn of the other recruits, on a regular basis. Lawrence is played by Vincent D’Onofrio, who notoriously gained 70 pounds for the role, and while that was an impressive piece of method performance, his acting goes beyond just gaining weight. D’Onofrio’s work is dynamic as we watch the transition from goofy recruit to stoic, damaged killing machine as Private “Joker” (the main character, played by Matthew Modine) is assigned to work with him, and make him an effective recruit. Joker succeeds, but a little too well, as Pyle has a psychological break, ending in tragedy just as they are set to ship out. Erney and D’Onofrio won acclaim for their roles, but not much else, I’m guessing because nobody was quite ready for the type of “acting” either did. But the more one watches the film, the more it’s clear that both deliver two of the most significant performances in modern film history, and they drive the action in one of the most devastating sequences in Kubrick’s career.

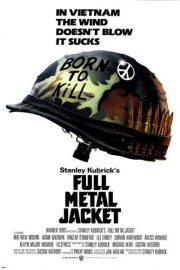

The basic training sequence is so vital and energized that for many, when the action turned to the battlefield of Vietnam, the results were underwhelming. Part of that was no doubt because Kubrick was trying to recreate “the shit” in England rather than location filming, but I think Kubrick was aiming less for realism and more for an emotional truth about war. As with his 1957 film, “Paths of Glory,” Kubrick is arguing against war by focusing on moral ambiguities. That’s why the basic training sequence is so important to the film, and also why one of the first things we see from the battlefield is Joker, who is a war reporter, in meetings with his editor about stories– the target of Kubrick’s probing eye here seems to be military propaganda, both the type that gets volunteers, without telling them the harsh realities of basic training, and the type that focuses on certain stories that will boost moral, but shelving ones that don’t fit the narrative the higher ups want to tell about what’s happening on the ground. In that way, Joker is a perfect protagonist, as he is someone who was brought into the Corp through the first type, and he becomes a part of the machine that propagates “the official story” when he hits the front lines. Modine is superb throughout, and that his character has “Born to Kill” written on his helmet, and a peace sign button on his uniform is representative of the complex world the character finds himself in, especially when he sees his first combat. He’s not really a soldier, at least not in the way his friend “Cowboy” (Arliss Howard) is, or “Animal Mother” (played by Adam Baldwin) is; even after a sniper attack, we see that he’s retained some of that individuality the others lost in basic training, although after the sniper has been taken out, he has to decide which message on his uniform is the true one. It’s not an easy one.

In a way, “Full Metal Jacket,” adapted by Kubrick, Michael Herr, and Gustav Hasford from the latter’s novel, The Short-Timers, is just as nihilistic and bleak in its view on war, and Vietnam in particular, as “Apocalypse Now.” That it hasn’t received the acclaim that unquestioned masterpiece has earned isn’t too surprising when you consider how wholly unique and hallucinatory Coppola’s film is; by comparison, Kubrick’s film seems old-fashioned in the way it’s narrative unfolds. But Kubrick was never quite as over-the-top in his cinematic approach as Coppola was at his peak, though he was always, arguably, more ambitious as a filmmaker. That’s definitely true with his instincts as a storyteller, which are on full display in “Jacket” as he takes the viewer on a psychological journey into Hell on Earth, as only Kubrick could. Some films take a piece out of the viewer; Kubrick always asked for a little more, and he earned that price every step of his career.