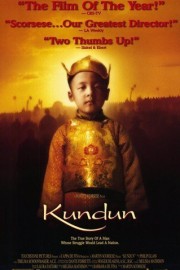

Kundun

Martin Scorsese’s “Kundun” is a remarkably beautiful film– arguably, the most beautiful film Scorsese has ever made; by comparison, his “The Last Temptation of Christ” takes place in a harsh, unsettling landscape. That both films were shot in Morocco (because the Chinese government would not allow “Kundun” to film in Tibet) makes this a surprising common element between both movies. Less surprising is the reservoirs of spirituality, and difficult search for peace, that connects both films; that comes entirely from Scorsese, who, before he turned to filmmaking, studied to be a priest. For over 40 years, moviegoers have reaped the benefits of that odd convergence of artistry and religious devotion in his films.

When I first went to see “Kundun” when it opened in Atlanta in January 1998, I didn’t understand the full context of the film within Scorsese’s filmmography. I’m pretty sure a lot of the people in the theatre with me didn’t know, either. It was on Monday of Martin Luther King Jr. weekend, and the theatre was very busy. A lot of families were wanting to go see “Mr. Magoo,” but the movie was selling out. That meant a lot of people taking their kids to “Kundun.” Needless to say, there were some walkouts from people who didn’t understand what they had gotten themselves into. That was the first major moment when I noticed people just randomly choosing a movie when the one they originally planned on seeing wasn’t available, and it baffles me to this day why people would do this.

Back to the film, though. The screenplay was written by Melissa Mathison (“E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial”) with the full cooperation of the 14th Dalai Lama, and it begins four years after the 13th Dalai Lama has passed. Monks come to the home of a young boy– they see something in him. They pose a challenge: they lay out a series of objects, and the boy chooses which of them are “his.” The ones he choose belonged to the 13th Dalai Lama; he is the one. Two years later, he is taken from his home, and begins his life proper as the 14th reincarnation of his Holiness, the Dalai Lama, or, as his advisors call him, Kundun. This is a politically-challenging time for Tibet, however, as the communists have taken over China, and their leader (Chairman Mao), looks to bring Tibet under the rule of China. Good for China, to be sure, and they claim it will be good for Tibet. However, for a people who have been peaceful and content (for the most part) with the life they have lived, Chinese occupation is undesired, and a violent possibility. This forces the Dalai Lama to become a leader earlier than is tradition, and to make choices that will have a profound impact on Tibet moving forward.

This is not a traditional biopic, in any sense of the word. Of course, the Dalai Lama is not a traditional individual. Whether you believe in reincarnation or not, the Buddhists do, and Scorsese and Mathison take us deep into the culture of Tibet and the Buddhist religion. Well, “deep” is a relative term; as deeply as a 135 minute movie can. Regardless of your religious persuasion, the film’s devotion to the idea of faith in a higher power, and how to tap into that during moments of duress, is truly affecting and engaging. Though there are moments of surprising playfulness at the beginning, when we see Kundun as a child, there’s a solemn spirit at the center of the film that is in line with Scorsese’s greatest films, and makes the film a fascinating double-feature with “The Last Temptation of Christ,” even as they approach their respective religious protagonists in very different ways; in particular, the final 30 minutes, which leads to the Dalai Lama’s exile in India, has some of the deepest emotions in all of Scorsese’s career.

A word about the beauty I alluded to at the start of this review: this really is a striking film on the eyes and ears. From a visual sense, costume and production designer Dante Ferretti’s work is detailed and exacting, which was important given the film needing to be made in Morocco, and it’s shown off marvelously by Roger Deakins’s lush, beautifully colored cinematography; both men do some of their finest work under Scorsese’s watchful direction, and all three areas were deservedly Oscar-nominated (although destined to get lost in “Titanic’s” wake that year). The film’s fourth nomination was for the stunning score by Philip Glass; a Buddhist himself, his frequent arpeggiations are inspired, and found an ideal home within the framework of Scorsese’s lovely, passionate movie that brought the Buddhist religion to the screen in a way rarely seen in the mainstream (though the film’s low box-office explains why it is rare). What will it take for Disney (or better, The Criterion Collection) to give this nearly 20-year-old film the high definition treatment so that audiences (and Scorsese fans) can finally give “Kundun” the credit it deserves?