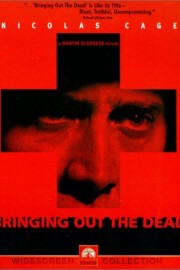

Bringing Out the Dead

When my mother and I first saw Martin Scorsese’s “Bringing Out the Dead” in theatres in 1999, neither of us particularly cared for it. The relative shapelessness of the narrative threw us, but I think the deep despair of the film, and the journey of Nicolas Cage’s paramedic, Frank Pierce, didn’t really sit well with us, either. Watching it 16 years later, however, I come to it from a different place. As a moviegoer, my appreciation for more ponderous films, as well as the works of Scorsese in particular, has deepened. However, it’s the changes I’ve undergone as a person that I think have helped me understand the film better. In 2000, my grandfather (my mother’s father) passed away after a four-month bout with cancer, and in 2013, my father passed away after a year and a half of significant heart issues that saw him going in and out of the ER, and dramatically changing his diet. It’s my father’s death that really came to the front of my mind watching “Bringing Out the Dead” again.

The first call we see Frank make in the film is a cardiac arrest of an old man, who locked himself in the bathroom after having a heart attack, and collapsed. When Frank and his partner, Larry (John Goodman), arrive, the old man, surrounded by family, has flatlined. Frank and Larry try to resuscitate him, but it seems hopeless. Frank then asks if the family has any music they can play; they have Sinatra. Almost immediately after the music starts playing, they get a pulse, this after Larry has already called it. They take the man to Our Lady of Perpetual Mercy Hospital in Hell’s Kitchen, with the family following behind them, and the old man will spend the next three nights in the chaotic ER at the hospital (which the paramedics dub “Perpetual Misery”). We will continue to get updates on him as the film progresses, as Frank makes his way back to the hospital, and forms a bond with the man’s daughter, Mary (Patricia Arquette). You would normally think Mary would be intended as a love interest for Frank, but it’s more of a need for human connection that draws them together than a desire for romantic intimacy. For Frank, Mary is an escape from the pain and suffering he will witness over the next three evenings as he works the graveyard shift, haunted by a lack of sleep, physically and spiritually, that has dogged him since he lost an 18-year-old homeless girl named Rose (Cynthia Roman) six months ago. He still sees Rose’s face as he looks out the window of the ambulance, hearing her voice asking him, “Why didn’t you save me, Frank?” Soon, he will be hearing the old man’s voice, as well, but in a very different context.

Scorsese is adapting a novel by Joe Connelly, who used to be a paramedic, with Paul Schrader, the screenwriter of some of his greatest films (“Taxi Driver,” “Raging Bull,” “The Last Temptation of Christ”). A common thread between the four films they worked on together is the way guilt, sin, and searching for a spiritual center that seems elusive are all part of the main character’s journey, that was something I didn’t really figure out when “Bringing Out the Dead” first came out. While I had seen all of Scorsese and Schrader’s films together, and really liked them all, I hadn’t really delved headlong into the subtext of them yet, or read deeper about them. I was still very much a novice film watcher in 1999; now, I’m more experienced, and can see clearly how much I needed to change from where I was as a person then to where I could appreciate films such as these on a deeper level. Personal experience matters, and when you’ve had your own spiritual conflicts and emotional turmoil, it’s easier to identify with characters like Travis Bickle or Frank Pierce or Willem Dafoe’s Jesus in “Last Temptation.” That doesn’t mean we would make the same choices they do in these films, but we can see why they make these choices. When we’ve seen loved ones die up close, as I did with my grandfather and father, we can understand better the weariness in Frank’s face and eyes, and why the guilt of losing Rose haunts him, because we’ve been to a similar place. I’m guessing a lot of people who saw the movie back then were in the same place I was in 1999; I wonder if some of those people would have the same experience I’ve had now, finding that time and life has better prepared them for Scorsese and Schrader’s film.

When I was reading about the film in preparation for this review, a quote from Schrader came up that was interesting. He said that, in adapting the book, “I intentionally took out a lot of the religious references of the book we adapted, because I knew Marty and I had done this so much. It was time to lay off it, because it was going to find its way in anyway.” It’s remarkable how correct he was, because as a filmmaker, Scorsese (a Roman Catholic, who once considered the priesthood before turning to film) cannot help but find religious and spiritual imagery in the stories he tells, especially with Schrader. The look of the film is fascinating. Shot by Robert Richardson, “Bringing Out the Dead” is very much a visual cousin to “Taxi Driver” in the use of overhead and point-of-view shots, as well as seeing the nighttime streets of New York’s Hell’s Kitchen as a Hell on Earth, making Frank’s desire for inner peace seem all the more futile. Peace is something that will not be found on these streets, doing this job, and Frank’s voiceover makes us think he understands this. At one point, he says, “I realised that my training was useful in less than ten percent of the calls, and saving lives was rarer than that. After a while, I grew to understand that my role was less about saving lives than about bearing witness. I was a grief mop. It was enough that I simply turned up.” Is this peace, or simply recognition of the purpose he plays? I’m inclined to think the latter.

It feels like “Bringing Out the Dead” is a film lost between more noteworthy periods of Scorsese’s career. It was his last film before “Gangs of New York” turned him into a perennial Oscar contender, and his second after a run that felt more commercial, starting with “GoodFellas” and including “Cape Fear” and “Casino.” It was preceded by another film, “Kundun,” that seems to have been forgotten not just by film fans, but by Scorsese’s fans, and that’s unfortunate, because both speak to one of the most important parts of Marty’s body of work, his approach to stories of the spirit. He is someone who doesn’t tug at the heartstrings like Spielberg, but rather travels, through the stories he tells, deep into the viewer’s soul, and asks them to feel. This film does just that, and in some of the most unexpected ways. There are moments of off-the-wall humor in the film, but they are simply intended to bring relief to the grim realities of Frank’s life. This is one of Cage’s most unique, powerful performances, and it’s all because Scorsese understands what makes the actor so fascinating to watch, and when the film requires that singular energy. Cage is the star of the film, but he isn’t the only standout, and I’d be remiss if I didn’t acknowledge the great work done by Goodman, Arquette, Ving Rhames as Marcus, the evangelical paramedic Frank rides with the second night, and Tom Sizemore as Wolls, Frank’s third partner in the film, and by far the craziest. One more performance that really sticks out, though, is Marc Anthony as Noel, a homeless man who is first seen begging for a drink of water in the ER, and continues to appear as the nights roll on. He takes the place of the old man in the ER after the old man has been moved to ICU. After we see Noel take his place in the ER, Frank does something that makes us wonder what Noel’s fate will be, and whether he might need the same care Frank gives the old man in the near future. If so, it may not be Frank doing it. He’s spent, and he’s ready to find peace, which Scorsese seems to give him at the end.