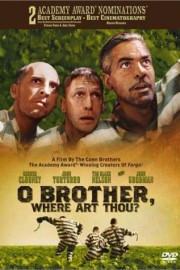

O Brother, Where Art Thou?

One of the beautiful gifts Joel and Ethan Coen have as filmmakers, and especially screenwriters, is their ability take potentially tricky material and turn it into something genuinely original. This is true whether you’re discussing an original work like “Fargo” or “Burn After Reading” or whether it’s an adaptation like “The Ladykillers” or “No Country for Old Men.” One of their most irresistible examples of this is 2000’s “O Brother, Where Art Thou?” It was their biggest hit up until “No Country for Old Men,” and the soundtrack produced by T-Bone Burnett became a runaway hit, but for die hard Coen fans, it’s a bit hard to swallow. It feels too…mainstream, as if that word can be used for any of their films (the one exception probably being “Intolerable Cruelty”), but it’s also a striking example of the brothers at their wily, woolly best. That’s what happens when you turn Homer’s The Odyssey into a Depression-era comedy about three prisoners who escape a chain gang, and go hunting for treasure. Like I said, tricky material turned into a genuine original. I bet Preston Sturges never thought of that.

Wait a minute, what does the great comedy director Preston Sturges have to do with this film? Well, while the story has been adapted from Homer (whose story the Coens claim never to have read before making the film), the title (and setting) is inspired by “Sullivan’s Travels,” a 1940s film from Sturges in which a film director wants to make a film about life in the Depression from the point of view of the common man. He’s best known for comedy, but the director played by Joel McCrea wants to make a serious drama called “O Brother, Where Art Thou?” Leave it to the makers of “Raising Arizona,” “Fargo” and “Burn After Reading” to pay homage to a film in a very direct way, but twisting it into offbeat lunacy. Ulysses Everett McGill (George Clooney), Pete Hogwallop (John Turturro) and Delmar O’Donnell (Tim Blake Nelson) are not your typical epic heroes, but rather three prisoners who just happened to be chained together. Everett (the smartest of the three) needs to break free, so he tells them a tall tale about how there is treasure he needs to get to in a handful of days, so they escape the Mississippi chain gang they are with, and make their way to where Everett says. The reality, however, is quite different- like Ulysses in Homer’s epic poem, Everett is just trying to get home to his wife (Holly Hunter) and kids after years being away, although the reason for his urgency is quite different. Along the way, the three find themselves recording a hit song with a black guitarist (Chris Thomas King’s Tommy Johnson) as the Soggy Bottom Boys; in the car with a notorious bank robber (Michael Badalucco); hunted by the ruthless Sheriff Cooley (Daniel von Bargen); baptized in a lake, which drastically changes Pete and Delmar; under the spell of three sirens washing clothes; and encountering a supposed Bible salesman (John Goodman) who, like so many, have twisted notions of what the Good Book says. In some of these moments, you can easily make one-to-one correlations to The Odyssey, but like their riff on the Book of Job in 2009’s “A Serious Man” or film noir in “The Big Lebowski” (which was their previous film to this one), it’s not necessary to connect the dots with the original source, and honestly, it’s more fun to just watch the Coens take you on a uniquely wild ride as only they can.

I can see where fans who don’t like this film are coming from, especially since the two films that preceded it are an Oscar-winning classic (“Fargo”) and their ultimate cult classic (“Lebowski”); this was the start of their self-named “trilogy of idiots,” which continued with their next two Clooney collaborations (“Intolerable Cruelty” and “Burn After Reading”), and seems to have added a fourth chapter with the upcoming “Hail, Caesar!”; the film is one of their first that feels like an unnecessary bid towards commercial success rather than iconoclastic rebellion; and while their collaborations with T-Bone Burnett have offered rich musical labors (most notably again in 2013’s “Inside Llewyn Davis”), it was another step in the marginalization of their frequent composer, Carter Burwell (whose scores added so much to “Fargo” and “Barton Fink,” among others), after his contributions to “The Big Lebowski” were limited. But expecting the Coens to always do things a particular way is absurd, and comparing one Coen Brothers film to another is, ultimately, an act of futility; they’re ALL worth seeing for one reason or another, even if they don’t always work (“The Ladykillers” may be their worst film, but I cherish it for one of the most singular Tom Hanks performances ever). Nobody but the Coen Brothers can concoct a KKK rally that leads to mass death from falling burning cross that begins like a twisted Busby Berkley musical number from the ’30s. Only the creators of “The Dude” could possibly find a narrative thread between spiritual revival, a guitarist who supposedly “sold his soul to the devil” for his talent, and yet sees Pete’s clothes empty, with a toad in them, and let one of it’s main characters honestly believe he was punished for laying with the sirens by being turned into a toad. And I defy you to think of a filmmaker who has found better ways to subvert Clooney’s classic movie star charms than having him play some of the stupidest characters of his career, because while Everett McGill is clearly the brains of this trio, he’s also not very bright himself. These are just a few of the reasons “O Brother, Where Art Thou?” is both classic Coen Brother lunacy and a natural lightning rod for debate among fans. You can always count on them to be clever bastards, but is there such a thing as being too clever for your own good? “O Brother, Where Art Thou?” makes a good case for that argument, but you know what? I’ll take “too clever” over uninspired any day of the week.