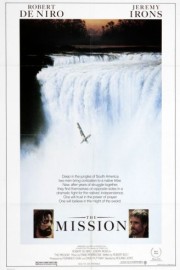

The Mission

I think my first real experience with regards to “The Mission” came in either 1998 or 1999 when I purchased the soundtrack by Ennio Morricone. You read that right. Several times over the years, my first experience with a movie has lied not with the film itself, but the music written for it. And the Italian maestro, though best known for his work in westerns like “A Fistful of Dollars” and “The Good, the Bad & the Ugly,” has been a big introductory course in those instances. (The other composer most like that is Hans Zimmer.) For many years, the score for “The Mission” has been a great piece of listening without a movie attached to it, but this year, given it’s subject matter (and that Martin Scorsese’s own Jesuit priest drama, “Silence,” is the movie I’m most looking forward to this year), the time was right to finally watch Roland Joffe’s film that inspired such a rapturous musical work.

The film begins proper on a truly haunting image, as two indigenous Indians take an 18th Century Jesuit priest, tied to a cross, a put him in the river, which leads to a falls that he drops down. The sight of a cross going over the falls is the enduring image from the film, and it encapsulates what will be the film’s narrative, as a whole. The priest had been sent to convert the Indians to Christianity and build a mission, but his message did not resonate with the Guarani he reaches out to. The death leads another, Gabriel (Jeremy Irons), to be sent out into the jungle, and he manages to connect with the tribe, and also comes into contact with a slave trader, Rodrigo (Robert DeNiro). There are other forces working against what Gabriel and his fellow Jesuit, including Fielding (Liam Neeson, who will also be starring in Scorsese’s film), are trying to do, as Spain and Portugal are in a political dispute over the territory, and that dispute puts the missions like Gabriel’s in danger. A Cardinal in South America, Cardinal Altamirano (Ray McAnally), has to make difficult political discussions that go against his faith, and it makes things difficult for Gabriel, who has taken an apprentice, Rodrigo, into the brotherhood. Rodrigo is in jail for murdering his brother (Aidan Quinn), who was in love with the same woman Rodrigo longed for, and seems ready to meet his fate until Gabriel comes to his cell, and offers a second chance. When the Portuguese army threatens their mission by force, Gabriel and Rodrigo come at an impasse in how they plan to meet it, with Rodrigo returning to his days as a mercenary as a way of helping those in their charge, and Gabriel leading them through his faith.

While the political quandary at the center of Robert Bolt’s screenplay is certainly compelling, it’s the spiritual dimension that grabs me the most about “The Mission” from a story standpoint. The most engaging storyline in the film is Rodrigo’s redemption, Gabriel’s faith in him, and how, in the end, his former self and present self must converge in order to become the man he feels meant to be. DeNiro and Irons make this material as compelling as they can, and that effort leads to the next most lasting image in the film, when the mission is under attack, Rodrigo is near death, and sees Gabriel leading his flock one, last time. The bond between the characters is complete, and that moment of two people meeting their destiny is powerfully seen by Joffe and his great cinematographer, Chris Menges (“The Killing Fields,” “Michael Collins,” “The Reader”). In that moment, “The Mission” feels like the film it is supposed to be, since the political parts of the story make the film drag when it should be achieving the stirring emotional heights Morricone brings it to in his score. It’s great finally having a movie to put the music to, but the score, one of Morricone’s finest, is unforgettable for a reason, and it’s because it reaches a level of transcendence the film it accompanies cannot, even though it tries really hard to.