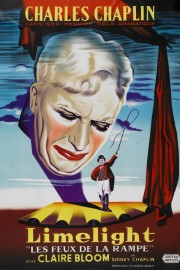

Limelight

I’ll admit to being taken aback by “Limelight’s” 2 1/4 hour running time, but then again, I knew very little of the film beyond it being one of Charlie Chaplin’s final films, and that it had a moment where he and the other iconic clown of the silent era, Buster Keaton, shared the screen together. Longer running times can kill comedy, but in fact, “Limelight” is a drama from the beloved silent clown. There are certainly moments of comedy within the film’s 137 minutes, but they are secondary to a story of resilience and love for Chaplin’s vaudeville comedian, Calvero, and a young ballerina (Claire Bloom) he saves from killing herself in the first scene of the film. She has much talent, but is melancholy about her prospects. After a bumpy beginning, they fall in love, and he nurses her back to health, and back to her career as a ballerina. Meanwhile, we see snippets from his act in daydreams, and they do not inspire confidence, and during a chance on stage, the crowd leaves in the middle of it. Tough times for Calvero, who is also an alcoholic (and whom always seemed to perform better drunk, he admits), but Thereza presents him with happiness, and they have a good life together. When she gets her big break, there is a possibility for a comeback for him, as well, but her meeting the composer of the show, whom she had known as a customer at a shop years before, throws complications at the life they have had together.

The best known of Chaplin’s films is his 1931 masterpiece, “City Lights,” and indeed, it feels like much of “Limelight” is lifted from that film, but seen through the eyes of a man whose best days as a performer were behind him. Chaplin retired the Little Tramp after his 1940 satire, “The Great Dictator,” and the evils of Hitler (who took the Tramps mustache for himself), but in the moments we see Calvero on stage with his routine, it’s impossible not to see the spirit of the Tramp come back to life in Chaplin’s physical performance. He never lost his gifts for physical humor, but “Limelight” comes to life through his personal interactions with Thereza, as Thereza is healed through the affection she has for Calvero, and Calvero feels rejuvenated through Thereza as she gets back her strength. In many ways, this is very much like the Tramp and the Flower Girl in “City Lights,” but played for dramatic effect over comedic sentiment, and infused with the wisdom of old age. It’s not a stretch to see Calvero as an autobiographical stand-in for Chaplin, and that gives the material an extra pop on the emotional front that may even supersede the famous emotionalism of “City Lights’s” final moments.

Two things really stick out in “Limelight,” however- the music, and the ending. The only competitive Oscar Chaplin ever won was for the lovely and wonderful musical score in this film, and it was much deserved. (He won it at the 1972 Oscars, after the movie was successfully rereleased after not having a good initial release in 1952.) The musical comedy Calvero traffics in is vaudeville at its finest, and Chaplin wins us over handsomely. The musical humor of the film also paves the way for it’s ending, during a gala put on in Calvero’s honor when he and a partner put on an encore that brings an appreciative crowd to its feet. His partner in the scene is none other than Buster Keaton, the other legendary comedic genius of silent cinema. Readers will know my appreciation of Keaton well, and indeed, his “Sherlock Jr.” is my favorite film of all-time, so needless to say, the idea of he and Chaplin in a scene together is what intrigued me the most about “Limelight” before seeing it. (Thankfully, it’s but a cherry on a delicious cinematic sundae.) Both actors are older now, and their dressing room scene before their performance has them basically playing themselves. (Keaton’s line of threatening to jump out a window when the next person says, “Just like old times,” had me so wanting to see the Great Stone Face perform one last death-defying stunt, only directed by Chaplin.) When they are on the stage, Keaton plays secondary to Chaplin, as befits the story, but Chaplin was a generous filmmaker for his old rival, and gave him plenty of moments during the routine to shine as he once did. The sight of the two legends on-screen together is inspiring, and one of the wonderful moments for fans of both actors in movie history.