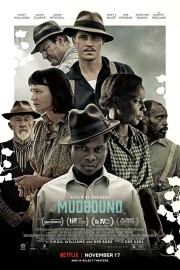

Mudbound

There’s a big chunk of storytelling going on in Dee Rees’s “Mudbound,” and it’s a primary reason why the film resonates as strongly as it does. It deals with racism as directly as any film has in recent memory, both in how it is learned from generation to generation, and in how the cycle can be broken by simply getting out of the only world you have known, and discover the larger one outside. It also deals with poverty and how dreams can be crushed by it. It’s a powerful piece of filmmaking when you put those two things together, and, since it’s available on Netflix, it’s, thankfully, readily available for the masses to see.

The first thing that deserves to be said is that Jason Mitchell will be winning an Oscar. It may not be for his heartfelt work here as Ronsel Jackson, a WWII soldier who has come to his family’s Mississippi home, and finds his new reality different than his military life, although it should be, but after sterling work both here and as Easy-E in “Straight Outta Compton,” it’s only a matter of time for him. When he gets home after the war, he’s surprising his family by going to the general store and getting things for his family. He’s still in his uniform, and is chatting up the store clerk (Kerry Cahill) and Laura (Carey Mulligan), the wife of Ronsel’s father’s boss, Henry McAllan (Jason Clarke). As Ronsel goes out the front door, Henry’s father, Pappy (Jonathan Banks) and another older man stop him, and make it quite clear that he still needs to go out the back door. Ronsel stands up for himself, but Henry comes in and emphasizes the point to him, and Ronsel goes out the back door, dejected. After four years overseas, where he has been commended for his service, and white people didn’t always see blacks as lesser, it’s a moment of shell-shock that is just the beginning of what he’s in store for back home.

While the harsh truths of racism in 1940s America take center stage in the second half of the movie, there’s a lot leading up to Ronsel’s reunion that needs to be said. Henry and Laura are married and have kids for a couple of years before they move to the Mississippi delta, with Henry’s Pappy, so that Henry can run cotton fields there. After he finds out he’s been swindled in renting a house, Henry and the family move into a shack on the field, not the situation they expected, to be sure. On the same road in the Jackson family, where Hap (Rob Morgan) and his wife, Florence (Mary J. Blige) have raised their family, and worked this land, for decades and generations. Henry may be the newcomer here, but he makes it clear to Hap who works for whom in his manner. Laura is more friendly and compassionate with Florence, even she has a sense of entitlement that is difficult to mask, but she’s at least not as obvious about it as Henry. Pappy, meanwhile, is full-bore racist, and nothing can change that painful truth, even seeing Ronsel in that general store. Henry’s brother, Jamie (Garrett Hedlund), moves in after the war, and shortly before Ronsel comes home, and he is very different from his brother. He always was, as we learned when he first met Laura, but the war changed him in a lot of ways, and it makes the homelife of the McAllans that much more complicated.

The film centers a lot of its focus on the McAllan family, but the Jackson’s are an important part of the story, as well. It’s clear that Hap and his ancestors have been working this land for a while, but rather than feel like slaves to the owners, Hap sees it as a point of pride that he has lived, and worked, and provided for his family like he has. He wants to own the land he works, and that is what keeps him going. When the fields get flooded, he struggles like everyone else, but he doesn’t see the struggle Henry does, because he’s seen it before. What makes life difficult for Hap is when he has to rent a mule from Henry to do the work after he has to put his own down, and when an accident keeps him unable to work, meaning the work Laura has offered Florence to help take care of her children, and Ronsel’s return to the home, is important for what freedom he feels like he has. Like I said at the start, Rees’s film, which she adapts from Hillary Jordan’s novel with Virgil Williams, is a big chunk of story, and this isn’t even including the bond that is stricken up between Ronsel and Jamie, which is some of the richest work in the film, as these two soldiers miss the front lines, at times, for very different reasons. Hedlund is terrific in the post-war scenes, capturing Jamie’s PTSD and turn of heart (compared to Henry and Pappy) when it comes to blacks quite well, and his scenes with Mitchell bring necessary heart and humanity to what is, otherwise, a pretty moody and dire story. Dire typically means “not good,” but it’s not meant to be. Rees’s film wears its heart on its sleeve, and it’s similar to the one we’ve seen before in “The Grapes of Wrath” and Spike Lee’s underrated “Miracle at St. Anna.” It’s not an upbeat heart, though, but it is an honest one, and I had a hard time looking away as Rees and her cast, all of whom do fine work, tell this story of sorrow and pain on the delta.