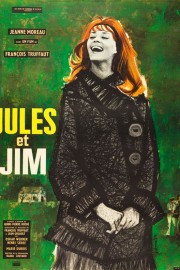

Jules and Jim

Francois Truffaut’s “Jules and Jim” is a beautiful tragedy about love and friendship. Really, that sums the film up quite well, but it barely scratches the surface of Truffaut’s adaptation of the novel by Henri-Pierre Roche, which he based on his own, young life, when he and his best friend fell in love with the same woman, a love that would come to define everything about them. That I found myself boundlessly overjoyed by Truffaut’s film is a credit to his gifts with storytelling and character, that this film which, in lesser hands, would be trite farce or a dirge tinged with anger, feels alive and romantic and passionate.

The film opens in 1912 France, when the Austrian Jules (Oskar Werner) and French Jim (Henri Serre) are writers and best friends. Their romantics travails have found them making mistakes (Jules’s fling with the flighty Therese) or odd choices (Jim with his nightly stands with Gabriele) befitting young men, while their friendship is the rock at the center of their lives. One day, Catherine (Jeanne Moreau) enters their lives after they go on a trip to see a striking sculpture in the Adriatic; her face looks like the sculpture, and immediately, both are struck with love. The trio are inseparable, and we think the tension of both men being in love with Catherine will separate them, but no, not yet. Their life is an idyllic one, where Jules pursues his love of Catherine, and Jim is a supportive friend. All is good until war breaks out, and Jules (who has gone to Austria with Catherine to marry) and Jim are separated, unable to really talk, as they end up on opposite sides of the conflict. This doesn’t even get into a huge chunk of the story, and this isn’t a small piece of the puzzle in the script by Truffaut & Jean Gruault.

One word that has made it’s way into American political discord in the past couple of years is to call someone a “cuck.” This is short for cuckold, and it refers to a subset of porn wherein a man watches his wife have sex with another man. That’s not the only way it’s used, of course, but if you’re a cuckold, your wife is humiliating you and calling into question your manhood by cheating on you with another. I kept thinking about this term during the second half of “Jules and Jim” when, after the war, Jim comes to visit Jules and Catherine at their Austrian home, where they are raising their daughter, Sabine. There are whispers around town as to whether Sabine is Jules’s biological daughter, although Catherine swears she is. Jules knows that Catherine has slept around on him, and she has rationalized it as only she could, yet he still loves her, and is desperate to hold on to her. He understands who she is, even if there is pain that comes with it. One day, she invites Jim into their house, and then, her bed. The pain of this is lessened for Jules because, he can rationalize, if it’s not him, at least it’s Jim. But responsibilities in Paris for Jim, and Catherine’s personality, makes even this ideal scenario complicated for all.

Truffaut adores these characters, even Catherine, and that is a huge part as to why “Jules and Jim” is one of his triumphs, and possibly, the best film of his I’ve seen to date. He loves the silliness they engage in during their pre-war lives together, and he loves the painful inability they will experience in not being able to recapture that after the war. Jules and Jim appear to be changed by their experiences in the war, of the possibility they faced of maybe, one day, killing the other, but they reveal themselves the same young men in not just how they view the world, but especially, their bond with Catherine. When they find that growing up means something else than just doing what they saw adults doing- getting married, having kids, having careers- they have some murky waters to wade in, and Truffaut allows them to have their heads above water just enough to find a path. Every moment of this film is a delight, and Truffaut has great technical skills in bringing it to life. The introduction has a joyous musical score and breathless narration that sets the tone for how we meet Jules and Jim, and Truffaut brings the form of a screwball comedy to a movie that will, ultimately, become a tragedy when Catherine’s nature gets in the way of happiness for all three. I did not see the end of this film coming (I hadn’t really read much about it beforehand), and it feels like a dark joke played by Truffaut on his characters, although, I have learned, it’s true to Roche’s novel. This is a film about innocence and light snuffed out by reality, and Truffaut makes it hurt, but not before he makes it feel euphoric to watch these three together, one last time, finally at peace with their lives together. Truffaut once said that he demanded that film reflect the joy of making cinema or the agony of making cinema, and that he was not interested in anything in between. With “Jules and Jim,” his third feature film, he did both, and it shines through in every frame.