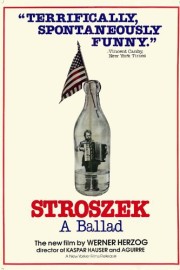

Stroszek

Werner Herzog likes to make movies you’ve never really seen before. Whether you’re talking about “Aguirre, the Wrath of God” or “Fitzcarraldo” or documentaries like “Encounters at the End of the World” or “Cave of Forgotten Dreams,” you’re likely going to get an experience that not only will you never forget, but one that will show you something new. “Stroszek” is a film I’ve been curious about since I read Roger Ebert’s Great Movies review of it, and curious is a great word to describe the film. One of the things I love about Herzog’s work is that, while it works within its own internal logic, it’s difficult to predict where the film is going to head, sometimes, even when you’ve seen it before. That is because Herzog is a one-of-a-kind filmmaker, whose films could only be the work of him. “Stroszek” is probably one of the definitive versions of that theory in terms of his narrative films.

The film begins with its main character, Bruno Stroszek (played by Bruno S.) being let go from prison. He has been in there for crimes committed in the throws of alcoholism, although one gets a distinct impression that he is mentally impaired, as well. He leaves prison with his passport, some money, an accordion, and a horn, and he goes back to his apartment, which a friend has kept for him, but first he goes to a local bar for a drink. He sees his ex-girlfriend, a prostitute named Eva (Eva Mattes), with a couple of jerks who have no problem beating up Bruno. Bruno and Eva begin a life together again, but life is miserable for them in Berlin. They decide to follow Bruno’s neighbor, an old man (Mr. Scheitz, played by Clemens Scheitz), to America, and specifically, Wisconsin, in hopes of a better life.

When you think about the structure of Herzog’s film, it’s actually a pretty basic immigrant’s tale, but “Stroszek’s” narrative meat- the characters and situations- are wholly unique to this film, and a big part of what makes the film as good as anything Herzog has ever made. As standard as the structure is, though, don’t expect a tale of triumph out of Herzog, because, as anyone who has followed his career even passingly knows, his worldview can be bleak. This is the American immigrant experience as seen through the cynicism and despair of “The Grapes of Wrath,” and it’s both heart-rending as well as wickedly funny to watch. Herzog has no room for America’s view of itself as the “land of opportunity” in this story, and he is brutal in how he views the “American Dream,” and all that it promises, here. Bruno is grateful for this journey with his friends because of how unbearable life had gotten in Berlin, but he’s not really surprised by how his time in America turns out. He knows the life, however mundane, he and Eva are trying to make for themselves lives was built on a rocky foundation to begin with. When she runs off with truckers she’s plying her trade with, he doesn’t react how an American filmmaker would have him react. He walks away, aware of what it will mean, since she was the one making money for them to live. He then has to stand by and watch as their home, a Fleetwood shack, is auctioned off, and then carted away. His old friend is still by his side, angry for both of them, yelling (in German, which they don’t understand) at the sheriff and banker who auctioned the home, and his old mind convinces them that it’s a conspiracy, which they are going to get revenge for in their old car, with a shotgun, as they steal money from a local barber. One of the things I greatly admire about “Stroszek” is the way Herzog mocks America’s image of itself, but doesn’t mock hard-working Americans, like the nephew who convinced Mr. Scheitz came to America to live with in the first place. Herzog doesn’t deal with caricatures in this film, and there’s a genuine affection for the forgotten working class, and even the banker, who is just doing his job, that makes this film more palatable than it would have been had it just been satire. The people in “Stroszek” remind me a lot of the people Herzog’s friend, Errol Morris, showed in his first two films, “Gates of Heaven” and “Vernon, Florida.” That Herzog used real people, essentially playing themselves, in all of these roles is one of the reasons this film’s perspective works, and is a continuance of Herzog’s interest in blurring the lines between narrative filmmaking and documentary filmmaking, which he did prior to “Stroszek” in “Aguirre,” and after in “Fitzcarraldo.” This is a big part of what makes so many of Herzog’s films special and wholly original, and a big reason why he’s resonated with me over the years.

A couple of other notes, presented outside of the context of a typical review format:

-Roger Ebert’s Great Movies review of “Stroszek” lays out the history of this film’s star, Bruno S., so I won’t repeat it here. What I will say is that he is endlessly engaging as the center of Herzog’s film, and the moments when he is playing music while still in Berlin are beautiful and haunting.

-The final scene, which Ebert’s review also discusses in detail, is as oddly fitting and bizarre a finale as Ebert’s description implies. I don’t know if it matches Klaus Kinski, on a raft, ranting like a madman while surrounded by monkeys in “Aguirre” in its impact, but it’s definitely unforgettable.

-As I mentioned on Twitter, I think “Stroszek” contains my favorite cinematic representation of America- two people in Wisconsin, each working the land in tractors. They are having a standoff over one part of the land, and both holding rifles while driving the tractors. I will never forget this image as long as I live.