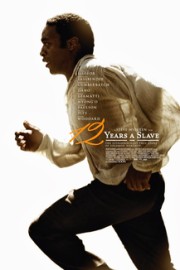

12 Years a Slave

Solomon Northup had an anything but normal life in 1841, but it was a life. He lived in New York with his wife and children, but he still needed to travel with papers to be able to show at a moment’s notice. Because you see, while Northup was a freeman, he was also a black man, and in the America of 1841, while it was possible to live up north free for someone like Northup, if you traveled south, you ran the risk of being caught up in the slavery that was still very much the accepted place for blacks at the time. Northup would find this out the hard way when the skilled fiddle player was approached by a couple of men, who purported to be part of a traveling entertainment show, offer Solomon a well-paying gig in Washington, which he readily accepts. After one drunken, celebratory evening, however, Solomon wakes up in chains, deceived, and on his way South when he is passed off as a runaway slave from Georgia, the first step in a 12-year nightmare where Solomon gradually loses hope of seeing his family again.

This is the remarkable true story of “12 Years a Slave,” adapted from Northup’s diaries with heavy heart, and no shortage of realism, by screenwriter John Ridley (“Red Tails,” “U-Turn”), and directed with unflinching honesty by artist-turned-filmmaker Steve McQueen. Their film moves too slowly at times, but I could say the same about McQueen’s previous film, the equally-direct “Shame” (I have yet to watch his first film, “Hunger”), and it hardly matters to the long-term impact of that film. Besides, since the bulk of the film deals with plantation life in the Deep South before slavery was abolished in 1865, and it’s the first real look at the life of a slave in America since the landmark TV miniseries, “Roots,” it’s important for us to experience every excruciating moment with Solomon up close, without escape, as his worst nightmare comes true. Besides, there’s not a single scene in the movie that doesn’t need to be there; the film moving too slow is more a pacing issue than a content one, and one that could have been fixed by little trims rather than deep cuts.

No matter; no movie is perfect, but what McQueen accomplishes perfectly with this film is putting us in the middle of an American horror story, and following him into the heart of darkness is Chiwetel Ejiofor, who plays Northup in a once-in-a-lifetime performance filled with steely resolve and beaten-down weariness. That may seem like an odd convergence of emotions, but wholly fitting for the role of Northup as he tries to survive his situation, and Ejiofor– a character actor known for performances in “Inside Man,” “Serenity,” “Dirty Pretty Things,” “Love Actually,” and “Kinky Boots” –is up for the challenge. The bulk of the film takes place after Northup has been sold into slavery, and is on plantations in New Orleans run by two very, different owners: the first by the more benevolent Ford (Benedict Cumberbatch), who’s head carpenter (Paul Dano) has several run-ins with the insolent Northup, who now goes by the name Platt; and then, after he’s run off of the Ford plantation, he finds himself owned by Edwin Epps (Michael Fassbender), a Biblical literalist who rules with a iron fist with his wife (Sarah Paulson), who can be caring, but also harsh, especially when it comes to Patsey (Lupita Nyong’o), who is a favorite of Edwin’s for more than her cotton picking skills. Ejiofor has some brutal emotional extremes to play in these scenes, and he nails them all in one of the great film performances of the past few years, which shouldn’t be too surprising for anyone who’s watched the actor over the years, or been familiar with McQueen’s earlier films.

Some difficult editing aside (as well as an iffy cameo by producer Brad Pitt as the righteous northerner who will be Northup’s salvation), “12 Years a Slave” stands as a great cinematic accomplishment: great production design, costumes, and makeup; great cinematography; great music (anchored by one of Hans Zimmer’s most subdued scores); and great performances (especially by Fassbender, Cumberbatch, Dano, and Nyong’o). This is the first major film to make us live and breathe what it must have been like on the plantations during the time of America’s greatest sin. That it’s the second film in less than a year to look at slavery, after Tarantino’s Oscar-winning “Django Unchained,” is a bit of a surprise, as is the fact that we haven’t seen as many cinematic glimpses of this era as we have the Holocaust, inarguably the other great sin of mankind against mankind. Maybe it’s just too painful for American filmmakers to get a hold of, since this happened not during wartime in Europe, but on our own soil, and went unchecked for decades (though longer, in reality) before the Civil War ended the practice for good. Maybe that’s why it needed to be two Brits (McQueen and Ejiofor) to be the ones to give us what might stand as the definitive cinematic representation of this tragic chapter in American history, and with racial tensions still high 150 years after the abolishment of slavery, their timing couldn’t have been better for a film that forces us to stare long and hard at our ugly past, and dare us not to feel ashamed by it.