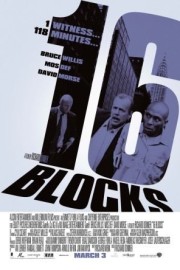

16 Blocks

Even for a longtime fan such as myself, it feels like a stretch to call Richard Donner a “great” director. Great directors have signatures, styles and motifs that distinguish their work from others. But there is something about Donner that makes him great, and it’s his desire to find authenticity in his characters, and creating a plausible reality, that flies in the face of a Michael Bay or Renny Harlin, directors who are more about empty thrills than finding something real in a film. (Although Harlin’s “The Long Kiss Goodnight” was definitely an exception, as was Bay’s “The Rock.”) Donner is regularly called a throwback to the directors of the old studio system, who worked within the confines of genre and specific collaborators and studios (in Donner’s case, Warner Bros.) to craft more formula works that lacked much in the way of individual fingerprints. It’s always seemed as though Donner has embraced this outlook on his work, but I feel like it’s also caused critics to undervalue him as a filmmaker, despite being the director of genuine classics such as “The Omen,” “Superman: The Movie” and the first two “Lethal Weapon” films.

It’s been about ten years since Donner’s last film, “16 Blocks,” and I have to ask…why? Okay, the argument could be made that Donner doesn’t fit the mold of what Hollywood is looking for in directors any more, that neither “16 Blocks” nor his 2003 film, “Timeline,” were successful enough to justify hiring him, but in an era of constant rebooting of properties and audience appreciation for nostalgia, will we really going to have to wait for the ever-elusive sequel to his 1985 classic, “The Goonies,” to give Donner another shot in the director’s chair? It’s true that he is in his 80s (85, to be exact), but I refuse to believe that he’s ready to hang it up just yet. If it does turn out to be his final film, though, I can’t imagine a more fitting way for him to go out than with “16 Blocks.” The way he handles Richard Wenk’s screenplay is in keeping with what makes him a great director, even if he isn’t a Hitchcock or Billy Wilder type of auteur.

“16 Blocks” tells a straightforward narrative about a veteran cop who has done his job too long, and is in the midst of a period of frequent alcoholic haze. He is Jack Mosley (Bruce Willis), and when we first see him, he is asked to babysit a crime scene, simply because that’s about all he is good for at this point in his career. The next morning, his superior is looking for him. He has an assignment- he is to transport a low-level criminal (Eddie Bunker, played by Mos Def, now known as Yasiin Bey) 16 blocks to the courthouse, where an Assistant DA is waiting to get grand jury testimony from him on police corruption. Bunker needs to be there before 10am, but it doesn’t stop Mosley from stopping to buy a drink. That decision will set them on a chase where they are hunted by some of the officers Bunker is set to testify against, including Jack’s longtime friend (David Morse, always an effective bad guy). If only Jack would do what he always does, Eddie would just be gotten rid of quietly, and all this could be over, but it’s like this situation enflames some within Jack that hasn’t been alive for years, and he remembers what is important about his job. This will be the longest 16 blocks of his life.

The idea of the director of “Lethal Weapon” and star of “Die Hard,” two of the seminal action thrillers of the past quarter century, collaborating on a police drama together had to be what made Warner Bros. interested in making the film. That’s an easy hook, but what I really like about “16 Blocks” is that it is far removed from the vulgar and manufactured thrills of those two classics, and feels more like a throwback to ’70s cop dramas like “The French Connection” and “Dog Day Afternoon.” There is a pace to the film that relies not on typical action beats but a sense of where the character of Jack is- hungover, walking with a limp, this is not someone you would rely on to get an important job done. (It becomes obvious that his selection to take Bunker in was a deliberate act of sabotage.) One of the best quotes I read about the film came from Roger Ebert’s review, when he called the film, “a chase picture conducted at a velocity that is just about right for a middle-age alcoholic.” I couldn’t describe it better myself. This isn’t a fast-cutting action scene like we’re used to seeing in a “Lethal Weapon” movie, or the superman Willis we get in the “Die Hard” series, but a deliberately paced chase film about a man who has spent too much time on the job, and too much time with a bottle in his hand, who gets a jolt of what it’s like to do something genuinely honorable in his duty to “Serve and Protect” for the first time in years, and it gets the smarts he had for the job working again. For Willis, this is one of the best performances he’s given in years, a return to the “everyman” quality that defined his John McLaine in the first “Die Hard” film, but with a sense of mortality that comes with age; watching the film again makes me even less interested in seeing another “Die Hard” film from Willis, which hardly seemed possible after the awful and absurd “A Good Day to Die Hard.” The film doesn’t wholly rest of Willis’s shoulders, however; this is ultimately a buddy film between him and Bunker, and once you get past the obnoxious qualities of Bey’s voice in the role, we can appreciate the genuine chemistry he and Willis have together. The ultimate theme of Wenk’s script is how people can change, whether it’s a criminal who wants to go straight like Bunker, or a cop who no one expects anything from like Mosley, and while it’s underlined just a little too hard at times, Willis and Bey make us care about these character’s respective evolutions throughout the film. They make a compelling pairing, almost as compelling as director and star make in this reflection of their prior successes. Ideally, my next Richard Donner film would star Mel Gibson, but if Donner and Willis wanted to make another film together, I certainly wouldn’t argue.