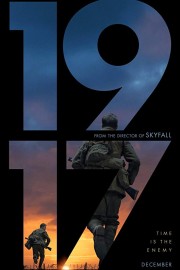

1917

Single take tracking shots are supposed to immerse us in what we’re watching, whether it’s in the commotion and events coming together at the beginning of “Touch of Evil” or a world of doors opening up for Henry Hill as he enters the Copacabana in “GoodFellas.” It’s obvious when a filmmaker is doing it just to show off, and almost invisible when it’s pulled off to perfection. To attempt to make an entire movie in that manner takes daring and imagination, as well as an ability to bring us deep into the story being told. Sam Mendes and cinematographer Roger Deakins have done just that in “1917.”

In terms of the narrative, Mendes and his co-writer, Krysty Wilson-Cairns, have one that is streamlined and simple: two British soldiers have to make their way up to the front lines of the British forces and deliver a message to call off their pending attack of retreating German forces. Intelligence has learned that it’s an attempt by the Germans to lure the British forces in for a slaughter. The attack is to happen in the morning, and so Schofield (George MacKay) and Blake (Dean-Charles Chapman) have until then to get the word, or up to 1600 British soldiers will lose their lives, including Blake’s brother. The story is inspired by Mendes’s paternal grandfather told him.

One of the tricks when it comes to “single shot” narratives are that we are not only looking for the seams between takes, but how does it aid the storytelling process. When Alfred Hitchcock made “Rope,” you can tell where the cuts are based on when he closes in on a dark place to make the “invisible cut.” With this or “Birdman,” shooting on digital, it’s a little more seamless, and save for two obvious places, I honestly had difficulty finding where Mendes and Deakins ended certain takes. What this endeavor does is challenge every part of the filmmaking team- especially the actors, stunt teams and effects crews- to be on their A+ game, and Mendes has his working on an astonishing level. In a year filled with remarkable technical storytelling accomplishments, “1917” is near the top tier, with the unparalleled Roger Deakins and his camera leading the way.

Something “1917” made me realize was there are not a lot of movies that really cause a physical reaction at times. I’m thinking how jump scares don’t really affect me on any level, at this point. There are a couple of moments on Schofield and Blake’s journey that resulted in such a reaction, including genuine emotion when the characters are faced with the complex nature of life and death during wartime. At 110 minutes, this has as much suspense and tension as any war movie ever made, and that comes from the way that Mendes and Deakins immerse us in their mission, with an assist coming from a Thomas Newman score that isn’t one of his most thematically-driven, but propels us through the story with the feeling of his best work. This is one of the most complete theatrical experiences I’ve had in a good long while, and seeing it in theatres is a must your first time watching the film.

The thing that makes the greatest impact on us in “1917” is the way that Deakins’s camera and Mendes’s story fold into an important idea for these two soldiers as they go about their mission. Keep moving forward. Regardless of the obstacles in your way, the mission is what matters. Your life is at the service of hundreds of others in a situation like this, and your ability to keep going, even when times get difficult, is how wars are won, even if it means putting ego aside for the greater good. This is one of the most idea-driven war films of all-time, and it leaves a mark on you.