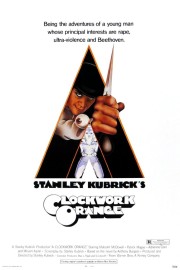

A Clockwork Orange

I’ve never read Anthony Burgess’s novel of the same name, but if friends who have– as well as my own familiarity with Stanley Kubrick’s films –are to be believed, Kubrick’s 1971 film based on the novel isn’t a strict adaptation of the text, but rather stands on its own as distinctly Kubrick’s own work. How does it hold up compared to films like “2001: A Space Odyssey,” “Dr. Strangelove,” or his next film, “Barry Lyndon?” That will be the question I hope to answer in this review.

This is the first time I’ve seen “Clockwork Orange” in 15 years, when I watched it as part of research for a paper about the movie ratings system. I didn’t know what to expect then, and in all honesty, I didn’t know what to expect now. As the film played, I realized just how much I had forgotten about the film and its tale of a sociopath named Alex (Malcolm McDowell) and his exploits in “ultra-violence” and anarchy in a dystopian, future Britain.

One thing that has imprinted itself vividly on my memory is the music. As he often, almost always, did, Kubrick populated the soundtrack of “A Clockwork Orange” with pre-existing music that fit effortlessly into the narrative. Beethoven’s “9th Symphony.” Purcell’s “Music for the Funeral of Queen Mary.” The “William Tell Overture.” Elgar’s “Pomp and Circumstance.” The musical classic, “Singin’ in the Rain.” However, Kubrick adds a twist in having these pieces adapted by Wendy Carlos (known, at the time, as Walter, not having yet undergone a sex change) via her Moog synthesizer and a new, electronic device called the vocoder. Nowadays, the use of either is commonplace in music, and anyone familiar with my own music is, no doubt, aware of the influence Carlos’s music for the film has had on me. The electronic reworking of these iconic pieces via Carlos adds a perverse, devilish menace to the compositions that enhances the film’s devious purpose. Along with original Carlos compositions such as “Timesteps,” which she wrote after reading the Burgess novel, this is one of the greatest, most influential, soundtracks in modern history. Of course, the same could be said of the soundtrack for “2001,” and many more uses of music by Kubrick, so that shouldn’t be that much of a surprise.

I mentioned the film’s “devious purpose” in the last paragraph. What is that purpose? Roger Ebert called the film an “ideological mess” in 1971, and despite the film’s Oscar nominations for Best Picture, Director, and Adapted Screenplay, Ebert wasn’t alone in his dislike for the film. It’s easy to see why, as Kubrick seems to have dulled Burgess’s satirical message to sympathize more with Alex, who– after one of his victims dies –is sent to prison, and then undergoes an extreme psychological treatment intended to force a negative, physical reaction whenever the patient is tempted towards violence and sexual debauchery. What does Kubrick feel about such “rehabilitation?” That’s where the film loses some of its focus, although it retains all of the power of its images and musical invention. It does feel like Kubrick is decidedly against such techniques, which are so extreme that they, no doubt, cause more harm to the subject, regardless their intended good to the community. Such experiments are the work of ultra-conservative minds who have no tolerance for outsiders and rebels. However, does that mean Kubrick would rather see Alex continuing his rampage of rape, pillage, and violence? I doubt it, but at the same time, by having Alex tell his own story via voiceover, the great filmmaker clouds the issue. I think the more accurate view of Kubrick’s philosophy in this film is that he sees such anarchy, unfortunately, as a necessary evil, of sorts. He doesn’t condone such behavior, but he also sees it as an important part of life; after all, without the dark, how can we possibly move towards the light?

Despite its seemingly-muddled message, however, Kubrick’s film is an iconoclastic masterpiece of sorts. A lot of that has to do with the remarkable images the director offers, and the unforgettable musical score Carlos creates with her wicked imagination, but in the end, the film really does come down to McDowell’s subversive performance as Alex. There is so much perverse joy, sharp wit, and heartbreaking pain, in McDowell’s work that it disappointing he didn’t see his own contributions to the film recognized by the Academy. Regardless of how we feel about Alex, he is our entry point, and our insider, in the world that Kubrick creates. We may not agree with his view of this world, but we can’t really argue with his disdain for “civilized society,” as those who try to rehabilitate him see it. Alex is one of the most fascinating main characters in movie history, and McDowell and Kubrick present him unfiltered and unapologetically. Few other actor-director pairings would be so confident in their process.