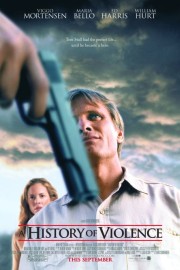

A History of Violence

No director messes with the mind better than David Cronenberg. I’ve only seen four of his films- and yes, they’re the last four- but I’m anxious to see the likes of “Videodrome,” “Naked Lunch,” “The Fly,” and “Dead Ringers” after watching them. Yes, I loathed his 1997 film “Crash” (about people who get off on car accidents), but it was a provocative piece of crap, but 1999’s “eXistenZ” was a head-twisting sci-fi thriller that put “The Matrix” to shame, and 2002’s “Spider” was an engrossing exploration into the fractured mind of a man whose childhood made him mad. Those last two films- as well as the previews for “Violence” (based- reportedly, quite loosely- on a graphic novel by John Wagner and Vince Locke)- made this film a must-see just to see what Cronenberg what had up his devious and demented sleeve next.

The story he had to tell was gangbusters, and ripe with possibilities. In the smalltown of Millbrook, Indiana, Tom Stall (Viggo Mortensen, “The Lord of the Rings”) lives the quiet life with his wife Edie (Maria Bello, “The Cooler”) and their two children Jack (Ashton Holmes) and Sarah (Heidi Hayes). He runs a diner in town, and is friendly with all of the members of the community. One night, he’s closing up the shop when two shady characters come in looking to score some quick cash. When things get violent, though, Tom- a pretty gentle person from the looks of him- springs into action and violently shoots and kills the perps, saving the lives of the people in the diner and becoming a local hero. But fame doesn’t come without a price, and it isn’t long before Tom is visited by some more shady characters, lead by a scarred, one-eyed gangster named Fogerty (Ed Harris, “Apollo 13”) who claims to know Tom as one Joey Cusack, a mafia thug from Philadelphia, a charge Tom emphatically denies, even if his unusually precise killing during the attempted robbery leads one to think otherwise.

From that basic premise is an idea that Cronenberg can freely shape to his very will to create a study in either the psychology of a killer who was made to kill by chance, the mind of a sociopath trying to hide his dark path, or a stinging commentary on how violence begats violence (when Jack has had enough of a bully’s pestering, he fights back with a violent outburst that suggests that brutality runs in the family), creating a vicious circle that is a tragic trait of American life. On that last part, Cronenberg creates a devastating cycle of cause and effect that’s impossible to shake, but the Canadian-born director fails to follow through on the psychological level of this promising- but ultimately unsatisfying- thriller. What happened to the filmmaker who created a delicate and daring drama out of an adult’s fragile and fragmented memory of childhood trauma in “Spider?”

The script is what happened. Cronenberg’s hand as a director is as assured as ever, as he keeps a steady pacing through the film’s 95 minutes; gets exemplary performances from Mortensen (up for the challenges of a fascinating role), Bello (who continues to establish herself as one of the toughest female supporting players in modern film), and Harris (a wickedly enigmatic presence); is given another evocative score by long-time collaborator Howard Shore (continuing to impress with or without Hobbits onscreen); and directs the flashes of violence with startling viciousness and confidence, aided by the sharp eye of cinematographer Peter Suschitzky (“Spider,” “The Empire Strikes Back”).

**Spoiler Warning: Potentially heavy spoilers into the film’s plot follow from here on out, so if you want to find out the whole story from the film, read no further.**

But the script does him no favors. Written by Josh Olson, it sets up ideas and storylines not satisfactorily followed through upon- so much so that one wishes Cronenberg had gotten his hands on the script and polished it to his own sensibilities. Start with the fundamental question of Tom’s true identity, which appeared to be what the movie would be about by the preview. This should be a mystery up until the very last scene. Is he a killer? If so, why doesn’t he remember, or even more tantilizing, why does he want to forget? Throughout the movie hints are given to answer these questions, but we never get the full explanation, or at least a full enough one that will still leave us asking questions after the movie. To be fair, we are still asking questions after the movie, just the wrong types of questions. Instead, we get the answer before the climax in a pretty straightforward manner from Tom. OK, he’s being honest with his wife, but not completely forthcoming, and too forthcoming for a viewer who may be intrigued by the secrets contained within his past. When he goes to Philly in the end to face his past (personified by William Hurt, miscast and ineffective as a mob kingpin), it should be a moment of revelation and suspense for the audience; instead, it’s merely a plot device to lead to a tidier resolution. How could Cronenberg let such a conclusion stand? It takes any dramatic weight away from the film’s final scene, haunting as it may be.

The character of Edie is another miscalculation…at least it appears that way. Early on her character is established as not being the conservative homebody you might expect in this story when her and Tom- with the kids watched over for the night- get kinky in a night of passion away from home. That potent lust is revisited later with added subtext when- after Tom’s past is more or less given to Edie- his wife- visibly upset- goes upstairs to get away from the husband she doesn’t trust anymore, and Tom violently attacks her. The rough sex that follows on the staircase would be considered rape were it not for the fact that they’re married- it’s the film’s most disturbing sequence. But what perplexes is the fact that by the end, Edie gives herself over to Tom completely in the heat of the moment, the idea being that she got off on it as much as her husband did. It’s hard to rationalize her reaction until you remember that first sex scene in the hotel, and begin to think that subconsciously Edie likes the bad boy within her husband as much as she loves the decent man she thought she married. But again, her reaction by the end of this sequence lacks consistancy to the disdain she shows for the violence unleashed within him over the course of the film. Had the scene not gone as far as it does (and gone another way), it would have had a stronger impact than the merely unsettling one it does have.

In the context of the film’s themes (or at least, the ones it tries to explore), the children needn’t be in the film. The son maybe because of his situation with the bully and the parallels between his actions and Tom’s, but the daughter is a waste of writing. There’s only one significant scene with her, and it’s a by-the-numbers child in peril scene that only works for what it presents Edie. Throughout the remainder of the movie, she exists only to be a cute little Americana girl, and nothing else. Why didn’t Cronenberg realize this?

**End Spoilers.**

The past few paragraphs I’ve given Cronenberg a lot of flack for issues not in his department to decide on this film- in the writing. As a whole, I still feel he made a good film, told a good story, and served the story he came on to tell. But I have to wonder, in pondering the logical flaws and thematic issues left hanging in “A History of Violence”- was it really the story he wanted to tell? I worry that it might have been. If so, one can’t help but wonder where his sharpest instincts as a storyteller went.