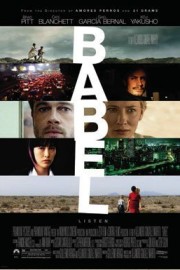

Babel

Regardless of how you pronounce it (I’ve heard two different pronounciations), “Babel” is an affecting and unforgettable experience that merits comparison with the year’s best films. The title refers to the tower man built in the Bible to reach the heavens. Seeing man’s success as a slight against him, he gave the people different languages, making communication impossible and work stop. This same concept is now at work in the film, conceived equally by screenwriter Guillermo Arriaga and director Alejandro Gonzalez Inarritu, who- like their previous films (2001’s yet-unseen “Amores Perros” and 2003’s intriguing “21 Grams”)- build their multilayered story from the aftershocks of one event, seen from different perspectives.

In “Babel,” the event is the shooting of American tourist Susan (Cate Blanchett, who makes you feel her character’s pain in a thankless role) in Morocco, where her and her husband Richard (Brad Pitt, stripping away his movie star glamour to show us Richard’s emotional pain and frustration as much with expressions and words as with words) have come to get away after their youngest child dies. Their children are at home in San Diego, where their maid Amelia (Adriana Barraza, whose compassion and guilt towards the children are undeniable)- unable to find a sitter for them so she can go to her son’s wedding in Mexico- takes them across the border against Richard’s wishes to the wedding while her nephew (Gael Garcia Bernal, dropping the romantic whimsy on display in “The Science of Sleep” for a more hot-blooded attitude reminiscent of his stellar work in “The Motorcycle Diaries”) drives them, sometimes putting his own life ahead of those in his car unwisely. The US government- naturally- considers Susan’s shooting an act of terrorism, but we’ve seen it’s an accident by two Moroccan children, whose goat herding father has given them the rifle to shoot jackel; however, to prove each other wrong about the rifle’s firing range, they begin targeting cars- for the distance they are away from them. The rifle was just bought from a hunting guide, who is linked to it through a Japanese hunter (Koji Yakusho), who can’t get through to his deaf-mute daughter Chieko (Rinko Kikuchi) since his wife’s suicide.

Inarritu and Arriaga- who apparently, unfortunately, have had a falling out- move from each of these four story threads effortlessly and in a way that gives each one weight and depth (a palpable sense of sadness is felt in the cinematography by Rodrigo Prieto and score by Oscar-winner Gustavo Santaolalla (“Brokeback Mountain”)). You feel the dilemma of the two Moroccan boys whose accident caused an international incident, and whose silence and fear caused by it leads to a tragic standoff on the side of a mountain where actions speak louder than words. The joy of seeing her son married turns into anger towards her paranoid nephew as a lovely- albeit illegal- day out for Amelia leads to misunderstandings when proper documentation can’t be found for the children in her care. A vacation away from the pain of a child’s loss leads to further pain as Richard tries frantically to get care for Susan, which leads to tense moments and outbursts fueled by frustration over the language barrier and the isolation of being far from help.

Most curious of all the stories is the one with the hunter and his daughter. In actuality, it’s about the daughter, with the father only glimpsed at. She isn’t linked to “Babel’s” central story in any specific way- she’s questioned some about her father’s hunting, but that’s it- but her own story ties in thematically to the idea of our need to communicate, even if we can’t find the right way of expressing it. Unable to speak, and worse, unable to hear. Chieko is cut off from the rest of the world- her only means of expression is physical. To tempt the boys (who can’t see past her handicap), Chieko removes her underwear from underneath her schoolgirl uniform. When she’s visited by the police at her home, she’s attracted to one of them, whom she invites back later under seeming desire to clear up some things about her father, but when she gets naked in an attempt to seduce him, you feel not the erotic charge of a possible hookup but the isolating pain of grief that sometimes can lead us to drastic measures in order to make a connection. Chieko’s story is the most engrossing- and indelibly moving- in Inarritu and Arriaga’s film, and the performance by Kikuchi is one for the ages. That’s ultimately the biggest compliment one can give “Babel”- in spite of its’ broad scope, wide range of characters (from a wide range of backgrounds), speaking a wide range of languages (at least four are spoken in the film), it’s a story that can be universally understood and felt. All you have to do is listen.