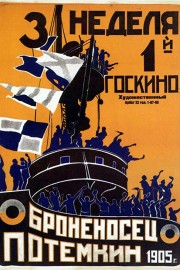

Battleship Potemkin

Sergei Eisenstein’s “Battleship Potemkin” is a great piece of cinematic history, even if not all of it is entirely accurate. As with so many historical films, it takes liberties with the original story for dramatic effect, and as with the best of them, the embellishments have not only become part of accepted history, but also, they add something substantial to the story that speaks to a larger context the filmmaker is looking to impart. But calling “Potemkin” cinematic history has another meaning, as well, and that is its place in the history of cinema. Eisentein’s film is one of the biggest leaps in cinematic style and storytelling of the silent age, on par with “Birth of a Nation,” minus that film’s awful racism, as Eisenstein was exploring the Russian concepts of montage and film editing in telling a story of the 1905 Russian Revolution. It’s been about 15 years since I last watched “Potemkin,” and it arguably had a greater impact on me now.

The film originally began life as a larger exploration of the Russian Revolution of 1905, but Eisenstein, prior to filming, paired it down to just the events on board the Battleship Potemkin. In Eisenstein’s film, the uprising begins with the crew aboard the battleship protests the poor rations being fed to them. (The first section of the film is titled, “Men and Maggots.”) It then turns into a larger rallying cry for those on the mainland in Odessa, where the ship is harbored, when the leader of the revolt (Vakulinchuk) is killed, and his body is displayed for all to see with the sign that he and the other shipmates revolted because of soup. The second half of the film then sees the aftermatch, as the Odessa authorities, and the Russian Navy, look to upend the rebellion taking place.

Eisenstein’s film was commissioned by the Russian government, therefore making it propaganda, but the thing that is fascinating to consider is that Eisenstein’s film feels very much like a call to arms, about the oppressed standing up to the upper class, or to those above them disregarding their basic rights, and it is a thrilling piece of film craft to experience, especially in the 1976 reissue I watched this morning with a score of Dmitri Shostakovich symphonies backing it. This is where Eisenstein’s theories on montage, and the juxtaposition of images to create a scene, come into play. Seeing each scene- with the film broken up in five sections, each focusing on a particular moment of the story- unfold feels as exciting as a lot of contemporary action movies do, and that’s partially because of the brute energy of the direction of actors and actions on the part of Eisenstein, but more importantly, in the way he edits everything together. I think I was just watching the film for the purpose of saying I had watched it all those years ago, but this morning, the film had a profound effect on me I did not expect, and I was energized by its storytelling in a way “Birth of a Nation” has never really had on me, even though all Eisenstein is doing here is building off of the ideas D.W. Griffith laid out in that movie.

Of course, one cannot discuss “Battleship Potemkin” without discussing the famous scene at the Odessa Steps, as soldiers open fire on the revolutionary citizens, mowing them down in one of the most iconic, and imitated, scenes in film history. In real life, the scene did not happen, but that doesn’t matter because of the suspenseful manner in which Eisenstein films and structures the scene. The baby carriage going down the steps is, easily, the most infamous moment due to the way Brian DePalma copied it in “The Untouchables,” but the way the soldiers move in lock step down the stairs, as chaos erupts with the citizens making their way down the stairs as the soldiers open fire, is as memorable a set piece as any filmmaker has done in a movie, and is ground zero for contemporary action cinema filmmaking. Anything involving mass chaos that requires building a plausible sense of space and tension, whether it’s the big fight at the end of “Avengers: Infinity War,” the shootout in the streets in “Heat,” or a battle between transformers in a Michael Bay film, owes a debt to Eisenstein’s masterpiece, and the way it established the way directors staged, shot, and edited action scenes for generations to come.