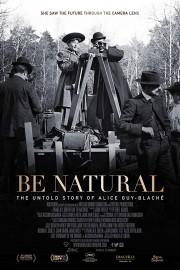

Be Natural: The Untold Story of Alice Guy-Blaché

Director Pamela B. Green calls her new documentary, “Be Natural,” a detective story, and that is not a stretch at all. It moves through its story with the kinetic energy, and sense of discovery, of “JFK” while telling a story as painful as “Hugo” as she introduces the viewer to the work of pioneering filmmaker Alice Guy-Blaché, who was the first female filmmaker. Film history is usually a dead-end for the masses (although it shouldn’t be), but if you want to witness the uncovering of one of the biggest lies film history has ever told, you do not want to miss Green’s film.

Guy-Blaché was a secretary to Leon Gaumont, the head of the Gaumont camera company, when the Lumiere Brothers introduced their first moving pictures in France in 1895. It was not long after before Gaumont turned to filmmaking himself, offering Guy-Blaché (who was just Alice Guy, at the time) the opportunity to direct so long as she continued to get her secretarial work completed. Her first film, “The Cabbage Fairy,” was made in 1896, and is widely considered the world’s first narrative feature. By the turn of the century, Guy had a career telling narrative stories, while many of her contemporaries like the Lumiere focused on documenting life, that would span over 25 years, see her in charge of her own studio, and make over 700 films between her time in France and the United States, where her studio, Solax, was right in the middle of the beginnings of the American film industry in…Fort Lee, New Jersey? Yeah, it would be a bit before California would become to center of the film world. But Guy, who married Gaumont production manager Herbert Blaché before moving to the US, was right at the center of the early film world in the first decades of the 20th Century. So how did she get all but forgotten by those who study film history? That is the mystery Green’s film unfolds over its captivating 103 minutes.

“Be Natural” is a work of investigative journalism, but it’s anything but a dry, informative documentary. Green is a motion graphics designer and animator originally, and the way she brings that experience to her journey into the past, and into the life, of Alice Guy-Blaché is enough to recommend the movie all its own. She uses graphics to chart both Guy-Blaché’s life, and her own investigation into that life, and with Jodie Foster’s narration, it gives us a complete look at both in a way that we get sucked into. Green finds people who knew Guy-Blaché, relatives and colleagues, recordings of interviews she did in 1963-64, as well as the work itself, some of which is available on DVD currently. As with a lot of early silent cinema, much of her work is currently missing, or known to be “lost,” but we see enough of it through the slips in this film to see what a remarkable, and bold, talent she was. (There is one film we see moments of, “The Sticky Woman,” that not only plays like an indictment of non-consensual touching by leering men, but has a punchline that I couldn’t help but feel like an “I Love Lucy” gag.) We see images from a lot of comedies she made, and not only do they point to Guy-Blaché as someone who liked to tackle challenging subjects (she made the first film with an all-black cast even), but they point to someone whose influence on what film comedy would become is arguably greater than the titans of Chaplin, Keaton and Harold Lloyd. (Oh yeah, and she was also synching film and sound a full two decades prior to “The Jazz Singer.”)

So, again, I ask the question- how did she get all but forgotten by those who study film history? The answer is simple- she was a woman, and the histories of early film were written by men. Her significance in the early days of Gaumont? Marginalized in the writing, if not entirely left out. The success of her studio in the US, The Solax Company? Attributed to her husband, who was not only a philanderer, but also headed west when film production started to make its way there; she stayed east, and her career never recovered, and her life was a struggle, as she continued to live with her eldest daughter, Simone, for the rest of her life. She would write her own memoirs in the ’40s, but no one would publish it until after her death in 1968. Every time film histories were written, she was either left out entirely, marginalized, or was attributed improperly to films, and she would be in communication always trying to set the record straight. As more and more people have become familiar with her work, the fight for recognition gets easier for the memory of Alice Guy-Blaché, although the work is far from done. (This documentary is the result of crowdfunding campaigns, and its release is minimal. I would argue it deserves to stand with the greatest documentaries on film ever made.) In an age where all sorts of content and films are available to audiences, the fact that I didn’t know who Alice Guy-Blaché was before I heard about this documentary borders on criminal. Pamela B. Green’s film not only stands as a tribute to her remarkable subject, but an indictment to the “boys club” that seemed hellbent to make sure she was forgotten. If you find this film playing near you, it’s one of the most important ones you might see this year.