Blade Runner- The Final Cut

Without question, the most influential thing that Ridley Scott did with “Blade Runner” was mindmeld science fiction with film noir to create a lasting vision of our future; “12 Monkeys,” “The Fifth Element,” “Dark City,” “Gattaca” and “Brazil” are films that followed in its wake. Another revolutionary thing that Scott did was to tinker and change his film after its 1982 release to bring it closer to his original vision of the film, which was hampered by studio concerns in 1982. He wasn’t the first person to do this (Spielberg did it, to lesser effect, with “Close Encounters of the Third Kind” two years prior), but his 1993 “Director’s Cut” was the most significant time this happened- in part, because it helped sway critical assessment of the film in his favor- and, I would imagine, was something George Lucas had in mind when he did the “Special Editions” of the “Star Wars” trilogy in 1997. In 2007, Scott released the “Final Cut” of the film for its 25th Anniversary, and made every version available so that fans could track the evolution of the film. I have not added that to my collection, in part, because I have never been as big a fan of “Blade Runner” as other movie lovers. This was my third time watching some version of the film (and second time with the “Final Cut”), and I continue to be in awe of the film as a visual and sonic experience, but have only muted feelings about the detective story Scott is telling with screenwriters Hampton Fancher and David Webb Peoples, based on Phillip K. Dick’s story, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?.

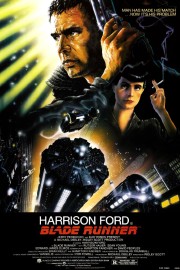

“Blade Runner” is set in 2019, at a time where the Earth is overpopulated, and suffering the weight of environmental havoc. In this atmosphere, the Tyrell Corporation has created Replicants, humanoids with the look of man, and memories implanted to make them seem more human, but ultimately, they are for slave labor off world. They are illegal on Earth, and if found, they are to be “retired” by special officers capable of discovering their true nature called “Blade Runners.” Rick Deckard, Harrison Ford’s character, is a blade runner, and after a murder at the Tyrell Corporation at the hands of a supposed replicant (Brion James), he is tasked with find a group of the newest model replicants that has escaped to Earth. The group is led by Roy Batty (Rutger Hauer) and also includes Pris (Daryl Hannah). A key figure in the investigation turns out to be Rachael (Sean Young), who is a replicant herself, and a bond forms between her and Deckard.

I think part of the reason “Blade Runner” just hasn’t resonated with me as it has other people is that, I just don’t see as much depth in the film as others do. I watched this film intently this morning, committed to giving it an honest assessment via its “Final Cut,” and when it comes to the story, it played more like an old-school detective thriller, indeed, a ’40s film noir, than it did an intellectual piece of sci-fi. The fact that Deckard is chasing non-humans certainly adds intrigue when it comes to character motivations, but the film has more in common, for me, with “The Maltese Falcon” and “The Big Sleep” than it does “A.I.” and “2001,” for example. I don’t feel like it asks big questions of the audience, but rather decided to tell an old-fashioned mystery in an original setting. Granted, I get why it garnered the reputation it has earned based on the look and sound of the film alone, along with Scott’s tinkering that removed studio mandated material (that Ford voiceover) and added more cerebral touches, but I feel like the questions it asks in terms of humanity vs. android are not as important as the film just working as a straight-up noir offering, but with a sci-fi setting. That’s enough for me to appreciate what Scott and his collaborators have delivered, and I will say that Ford’s performance as Deckard is probably the closest he had gotten to that Bogart swagger for most of his career (and that includes the time he literally took over a role played by Bogart in the remake of “Sabrina”), although his recent return to Han Solo in “The Force Awakens” gives me that vibe, as well. Like the old-school films like “Falcon” and “Casablanca,” Ford is surrounded by a cast (which also includes Edward James Olmos and M. Emmet Walsh) that gives life and energy to their supporting roles that gives the film texture, and Ford people to bounce off of effortlessly.

This was Ridley Scott’s first film since “Alien,” and it’s easy to see why this 1-2 sci-fi punch landed him an all-time position as one of the great Hollywood visionaries. Here, his 21st Century Los Angeles is unlike any other we had seen to that point, always raining, with a thick layer of smog muting the colors of the massive digital billboards and screens around the city. It still has its feet on the ground, and takes us to some seedy locations, as a good noir does, but production designer Lawrence G. Paull, cinematographer Jordan Cronenweth and visual effects supervisor Douglas Trumbull (“2001: A Space Odyssey”) created a new standard for sci-fi and fantasy that extended not just to the films mentioned above, but also, one could say, “The Terminator,” “The Crow,” Burton’s “Batman” and Nolan’s “Dark Knight” trilogy. I can see why people responded to what Scott, Trumbull and co. had to offer, and the score by Vangelis only adds to the atmosphere and sense of originality Scott is offering audiences in this film. In 1982, there was nothing else quite like it, and even if I don’t love it like others do, I can freely admit that 35 years later, Scott’s vision of a bleak future still sucks us in.