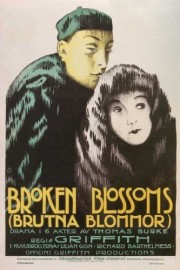

Broken Blossoms

After back-to-back epics, D.W. Griffith scaled back, and told a story of love and pain that has haunted me since I first watched it a few years ago, “Broken Blossoms.” The fact that it is an interracial love, between a young white woman and an Asian man who comes bringing a message of piece, but instead finds himself in the squalor of London, is something of a surprise, since Griffith made “The Birth of a Nation” four years before, and riled up many with his insensitive portrayal of blacks and the Ku Klux Klan. However, although he followed up “Nation” with a powerful, impassioned epic of tolerance (his 1916 masterpiece, “Intolerance”), he wouldn’t come full circle as an artist when it comes to race until “Broken Blossoms.” It’s quite an evolution.

Of course, even with its more tender portrayal of racial issues, “Broken Blossoms” remains dated in many of its sensibilities, which reflect the more-discriminatory nature of the times. For example, to play “The Yellow Man” (as he’s known in the titles), Griffith cast a Caucasian, Richard Barthelmess. Of course, such casting was often the case in the early days of cinema– which still used blackface to portray African Americans, at times –but now, with the globalization of cinema, such a choice would seem unheard of, even though it’s still known to happen, such is the nature of the business. And the film is rife with stereotypes, starting with the character being known as “The Yellow Man,” and continuing through him starting out as a peaceful Buddhist; later becoming addicted to opium; and also becoming a shopkeeper when he gets to London. Despite those insensitivities, acceptable at the time, the character is brought to thoughtful life by Bathelmess, and makes a wonderful foil for Lucy, the other “broken blossom” the title refers to.

Lucy is the daughter of a prizefighter, Battling Burrows (Donald Crisp), who has raised her since one of his girls thrust her into his hands as a baby. Burrows and Lucy also live in the Limehouse district where The Yellow Man resides, and their life is just as miserable. Well, Lucy’s is, as Burrows takes to physical and verbal abuse when he gets berated by his manager for his drinking and womanizing. How miserable is Lucy’s existence? She must use her fingers when Burrows wants to see her smile. And with all the women she meets on the street warning her against marriage and prostitution– her only escapes, it seems –she seems destined to be in this situation forever. It’s after one, particularly brutal beating when she first meets The Yellow Man, who has admired her from afar, and together, they find a happiness they haven’t known in a while.

Lucy is played by the legendary Lilian Gish, one of the most famous faces to come out of the silent era. She was a favorite of Griffith’s, and fell in love with the great director in a collaboration that included not only this film, but also “Nation” and “Intolerance.” She was 23 at the time they filmed “Broken Blossoms” together, but she still had the innocence of face to play Lucy, not to mention the acting skills. Acting during the silent era must have been alternately easy and difficult, but Gish, who would make her last film in 1987, makes it look effortless. This is one of the great performances in movie history, by one of the greatest actresses, whose legacy of impassioned, independent females– even in a role of weakness such as this –continues to inspire movielovers. (Note to self: re-watch “Night of the Hunter,” with another of Gish’s iconic performances, soon.)

Sadly for them, Lucy and The Yellow Man’s love is forbidden during the time they live in, and when Burrows’s manager sees Lucy in The Yellow Man’s shop, we know that the romance will be doomed. The revelation leads to the unforgettable scene where Lucy, after returning home, is confronted by Battling Burrows, who corners her into a closet when he comes after her with an axe. The Yellow Man will try and save her, but unfortunately, his efforts will be in vain. However, Griffith allows the lovers dignity that a lesser filmmaker may not have afforded them with a conclusion that is powerfully moving, and hauntingly beautiful. “Intolerance” is the director’s greatest achievement, but “Broken Blossoms” is his most emotional masterpiece, and after 94 years, it still packs a wallop.