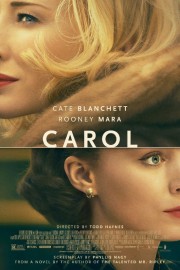

Carol

I’m still not as familiar with Todd Haynes’s films as I probably should be, but the three I’ve seen show a penchant for outsiders in times where conformity was rewarded. That two of those involve forbidden romances in the 1950s is probably a bit surprising, but that’s more a matter of timing in watching Haynes’s work than anything. (The previous film was his Oscar-nominated 2002 film, “Far From Heaven.”) Here, he’s working from a delicate script by Phyllis Nagy adapted from a novel by Patricia Highsmith called The Price of Salt, published under a pseudonym. This was not the suspenseful work of her Strangers on a Train or Tom Ripley novels, but rather a semi-autobiographical book about a relationship between an older mother whose marriage is failing and a young store clerk. What really garnered it such attention wasn’t that it was about a romantic relationship between two women, although that certainly helped, but that it found something of a happy ending in their story. Haynes and Nagy keep that ending in the film they’ve made of the book, but “Carol” isn’t an optimistic look at changing attitudes- there are harsh truths the characters still must grapple with because their choices have hurtful consequences to themselves, and possibly those around them, as well. The sad thing is that some of those consequences could very much apply to the modern day, at least in some places in the country. That makes “Carol” of particular importance to here and now, because it shines a light on realities we’d like to pretend don’t exist today. Yes, Carol and Therese could get married if they wanted now, but a stigma would still be placed on them in some pockets of society, whether it’s based on religious beliefs or simple prejudice. But that has no bearing on Haynes’s lovely film, but merely a realization that much hasn’t changed in 60 years.

“Carol” is not quite as daring in it’s structure as you would expect, as it feels very much like your typical period piece released around Oscar time, but the key to it’s success is not a sense of revelation in it’s craft qualities, such as Edward Lachman’s cinematography and Carter Burwell’s score, but in the powerful pull of Haynes’s storytelling, as well as the performances by Cate Blanchett as Carol Aird and Rooney Mara as Therese Belivet. When they first meet, Carol is looking for a doll for her daughter, and immediately, there is an unspoken pull between her and Therese. Carol is in the midst of a divorce from her husband, Harge (Kyle Chandler, adeptly showing masculine insecurity), where a previous relationship between Carol and her friend Abby (Sarah Paulson) looms large, while Therese is dating Richard (Jake Lacy), although she hasn’t committed to the relationship emotionally. Something in Carol awakens Therese’s passion, however, and after Carol leaves her gloves at the store, a relationship blossoms that gives both deep happiness, but while Therese, who wants to be a photographer, seems to be in a state of bliss, Carol is about to have her life turned upside down when a road trip between the two leads to a heartbreaking choice. Blanchett and Mara are extraordinary at playing the unspoken moments between these characters, and carry the film beyond it’s trappings as an otherwise typical drama and turns it into a revealing look at the pressures of conforming to society rather than following your heart. Haynes guides them through the erotic bond between these two with piercing humanity, resulting in something truly special happening before our eyes. “Carol,” both the character and the film, pulls you in, and you aren’t the same afterwards.